[Last modified: March, 24 2019 07:55 PM]

Scroll down to find the object you want to read about.

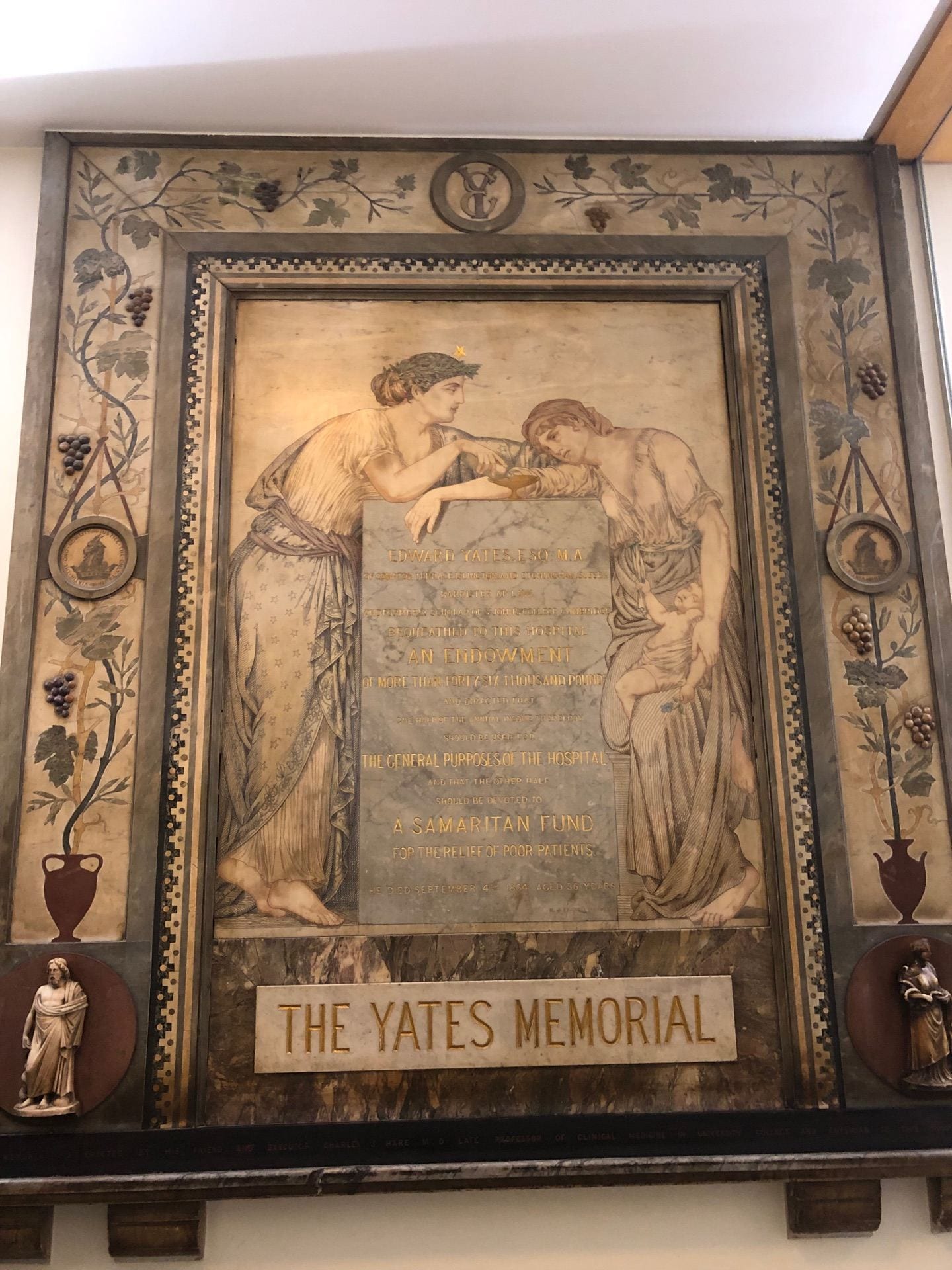

Yates Memorial

The next few slides will show details and features of the memorial, and explore how they connect to the theme of sacrifice.

Click here to return to the object’s page.

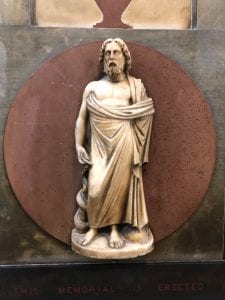

This is the symbol of Aescalipius, a major symbolical statuette representing a greco roman God found on the lower corner of the Yates Memorial’s frame. It represents Zeus’ thunderbolt, and a snake which represents life and longevity. From the 5th century BC, the cult of Aescalipius spread widely. Pilgrims used to visit healing temples and make sacrifces to him and his daughter, in the hopes of being cured of their illnesses. Triqueti used this imagery to celebrate the idea of sacrifice for the scope of well being.

IMAGE FROM: https://www.healthcaresuccess.com/blog/branding/why-caduceus-doesnt-belong-in-your-branding.html

This is the Greco-Roman god Aescalipius. In mythology, he represents the art of healing, which he learned from the centaur Chiron. His fate was tragic: Zeus was fearful that he would render all men immortal, so he slew him with a thunderbolt. Aescalipius represents the mythological sacrifice for the human desire for the ability to heal.

Confessio Amantis

Read on to see how the Confessio Amantis fragment relates to religious sacrifice.

Click here to return to the object’s page.

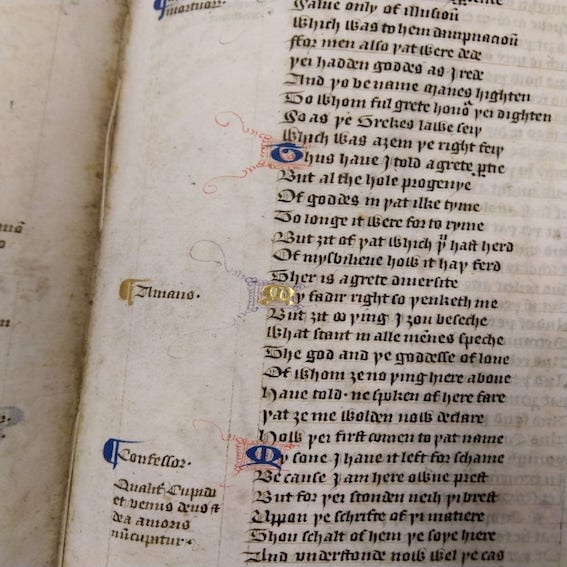

The Physician’s tale, one of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, is told in the ‘Confessio’. Both Chaucer and Gower were writing at the same time and it was common for contemporary poets to rewrite and comment on eachother’s work. This tale’s central theme is one of sacrifice. The story is about a noble woman, Virginia, who consents to her death after having been given a choice by her father: either be shamed by the judge, Appius, who has tricked her, or sacrifice her life instead. She chooses the latter.

Many of the tales in the ‘Confessio’ are religious in nature – during the middle ages, the power of gods and goddesses was unquestioned, and so were deeds of sacrifice made for them. In a deeply christian society, the notion of chivalry was held up as the ideal; a sacrificial way of life, as one is prepared to give up one’s own selfish desires for others needs.

IMAGE FROM: https://www.buonconsiglio.it/index.php/en/Buonconsiglio-Castle/castle/Itineraries/The-Loggia-del-Romanino/Lunette-Lucretia-s-Suicide-and-the-Killing-of-Virginia

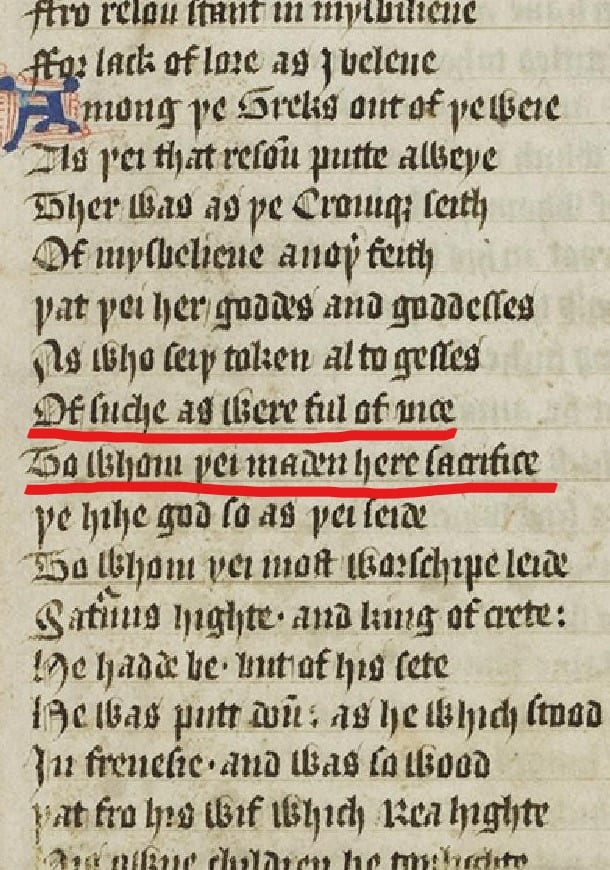

“Of suche as weren full of vice

To whom thei made here sacrifice”

These two lines appear on the first page of our manuscript fragment. As you can see, the verse is written in middle english. By looking at the scholar George Campbell Macaulay’s 1901 translation of Gower’s work, we find that these lines are describing the Ancient Greek attitude towards their Gods. Gower is making the point that, despite the Greek Gods being ‘full of vice’, people still made sacrifices to them. Gower goes on to tell the stories of many Greek myths and also those of ancient Egyptian and Chaldean religions.

Statuette Offerings

Read on to see how the text relates to the theme of sacrifice.

Click here to return to the object’s page.

In the Sanctuary of Aphrodite where the statuette would have served as a sacrificial offering to the goddess, other rituals were believed to have taken place regarding offerings far more personal than that of a Cypriot craft.

Herodotus, the ancient historian, documented the lives of ancient populations of Greece, Rome and Egypt. In his Histories he wrote about women’s involvement in religious practices. They were allowed great responsibility during ceremonies, could become priestesses and also said to have had important duties to fulfil. Going into detail about the practices that take place before marriage, it is explained that ‘women must go to the temple of Aphrodite and wait there until a man throws a silver coin’ (of any amount) into their laps: the initiation of a sacred sexual rite. The act of offering one’s body to the stranger in exchange for capital serves to honour the goddess, support the temple and inhibit the woman from ever being tempted to stray from her vows. The temples were made rich, and not only full of statues, these were also the owners of thousands of ‘temple-slaves’, courtesans whom both men and women had dedicated to the Goddess.

The tale of Rhodopis

Sir Edward Poynter’s roundel design for ‘Rhodopis’ tiles in South Kensington Museum, Grill Room. Courtesy of the V&A.

As she was bathing one day at Naucratis, the sandal of Rhodopis was stolen by an eagle, flown to Memphis and dropped into the lap of the Egyptian King who subsequently did not rest until he had tracked down the fair owner of the shoe to make her his queen…it is a familiar story – referred to as the earliest version of Cinderella – however is one with a past more complex. Having lived most of her life as a sex slave, this woman was sold and passed between proprietors. Once liberated, ransomned by a migrant merchant, Rhodopis is said to have chosen to continue her life as a heteaera (high class prostitute) saving the profit from her income to send iron spits to Delphi. These are said to have been seen by Herodotus and serve as another example of how the body is sacrificed for religion as offerings to the oracle.

Ripped-out finger and tendon

Read on to see how the ripped-off finger relates to religious sacrifice.

Click here to return to the object’s page

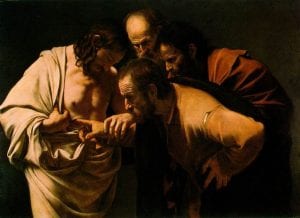

The finger holds a very important place in the Christian tradition. Whether it stands as a symbol of creation or pain, it is invested with a strong meaning in biblical scriptures and especially in religious art. The finger’s imagery is found in paintings dating from the early medieval period during which the depiction of God was not tolerated. The Hand of God was initially represented as the Craftsman’s tool, as the source of his creation. The artistic shift which occurred throughout the Renaissance enabled the emergence of a darker, more realist painting, along which the symbolism of the finger shifted. Caravaggio and the “Baroque” transformed religious art, exaggerating dramatic effects as in the “the incredulity of St. Thomas” which portrays St. Thomas inserting his index in the Christ’s wound, realizing the Christ is standing in front of him. The emphasis on the painting’s gory aspect through Caravaggio’s interplay of lights reminds the Christ’s sacrifice, shifting the importance of the finger in religious imagery.

Fresco from Sant Climent de Taüll, Catalonia, Spain.

Early medieval religious paintings do not portray God as a human figure but only his hand, recalling the Creator’s craft. Such representations conveyed a symbolic religious meaning to the hand and its fingers. In Catholicism, the sign of the cross is made with the tip of the index and of the middle finger, preserving this important religious connotation associated to our fingers.