[Last modified: March, 25 2019 12:05 PM]

Plantasia, Symphony for a Spider Plant

Throughout history, people have attemped to control the natural world, from agriculture to domestic pets. We were taking pieces of nature and trying to rearrange it to fit our society and the spaces we built. We are reproducing the natural world through our human perspective. The institution of the natural history museum is an example of that. We also want to own parts of the natural world, particularly in today’s times, when many of us live in cities, surrounded by man-made objects, away from nature. We also carry our assumptions and prejudices and these often influence our thoughts and decisions. These can be easily misguided, especially when they concern the natural world – for instance, when we encounter a species for for the first time. Humans transform and reproduce the natural world, putting it in an unnatural surrounding, for purposes of education, collection or decoration. Explore the objects related to this idea below.

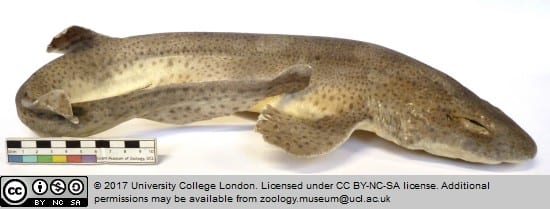

Freeze-Dried Catshark

Collection: The Grant Museum of Zoology

Object ID: V1081

Physical Description: 40 cm long, adult female freeze-dried specimen of a cat shark

The first object is a freeze-dried specimen of small spotted catshark (Scoliorhinus canicula), also known as a lesser spotted dogfish. It’s a common and widespread fish found around the coasts of Britain and Ireland. At first glance, a freeze-dried specimen can be confused with one prepared using the more common taxidermy. The freeze-dried shark has the skeleton, muscle and organs still inside it – nothing has been removed. It has been freeze-dried using a vacuum – this is a relatively new technique when it comes to animal specimens and can only be used on small objects as the cold would not penetrate deep in case of large specimens.

Freeze-drying is a technique that allows us to view the dead specimen looking almost identical to what it looked like alive. It is perhaps the closest we can get to reproducing the image of an alive animal after its death. Of course, this method is not perfect: pests often get to frozen specimens and cause damage – as if nature was reminding us that we cannot recreate it the way we want in a museum setting.

Taxidermy Echidna

Collection: The Grant Museum of Zoology,

Object ID: Z7

Physical Description: taxidermy specimen of an echidna, back feet artificially turned to face front

This object is a mounted taxidermy specimen of a short-nosed echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), also called the spiny ant-eater. The echidna, native to forests and deserts of Australia and New Guinea, is one of the two egg-laying mammals (along with the more well-known platypus) known to humans.

During taxidermy the creator uses the skin and outside parts of the animal to reconstruct it – this involves making artistic decisions and having assumptions about what the living animal looked like when it was alive. Taxidermy specialists are artists rather than scientists – it is very likely that they will make mistakes during the preparations and not capture the likeness of the live animal. During the process, the animal is reproduced using the taxidermist’s vision – the way a viewer will perceive it is not how it actually looked like, but rather how the artist interpreted it.

The echidna specimen is an excellent example of when a taxidermist gets something wrong about the living specimen’s image. An echidna, unlike other animals that walk on 4 legs, has its feet turned away from each other: the taxidermist used his assumptions about the animal world and so decided to twist the echidna’s feet the other way when mounting the specimen

Compare the taxidermy echidna with this living echidna. Note the feet are turned the correct way round!

Learn more about taxidermy and extinct animals from this National Geographic video.

Sydney Parkinson, artist of Cook’s Endeavour Voyage

Collection: The British Museum

Object ID/ISBN: 0708111726

Physical Description: 300 pages, including unusual, beautiful and historic illustrations and English text

Author: Sydney Parkinson (illustrations), D.J. Carr (editor)

Publication: British Museum (Natural History), Australian National University Press (1983)

This is a book of illustrations made during the Pacific voyages of James Cook by the artist Sydney Parkinson between 1773-1784. Different authors have written on the types of drawings by Sydney Parkinson and their comments are included in the book. The book will appeal to those interested in results of Pacific voyages as well as to botanists and zoologists interested in the plants and animals of the Southern Hemisphere.

Going on travels to lands far away, people often relied on reproductions of foreign objects, like plants or animals, to record what they look like. Images, like drawings and paintings were used to remember the objects and to show what they look like to people at home. These drawings are another example of how humans reproduce nature: a viewer can only admire the image of the plant, seen through the eyes of the artist.

You can download the book from the Australian National University Open Research Library.

Venus Flytrap Houseplant

Collection: Royal Kew Botanical Gardens

Object ID: n/a

Physical Description: small Venus flytrap in a plastic pot

This is a houseplant of the carnivorous Venus Flytrap. This plant is native to the southeast of United States and feeds on insects and arachnids by trapping them inside a “pouch” at the top its leaves. Today, the Venus Flytrap has become a popular houseplant, especially among the more adventurous of plant keepers. Many people all around the world like to have one on their windowsill, unfortunately this results in the plant doesn’t get enough moisture and protein.

By taking the Venus Flytrap out of its natural surroundings, we take it out of context and in fact, strip it of its natural lifestyle. We are reproducing the natural state of the plant, making it act differently and placing it in a human context. If you can’t see the plant in its natural surroundings, is what’re looking at the real Venus Flytrap? Or a mere reproduction that you keep in your house?

In a busy, technology-driven world, people will strive even more to be connected to nature, even if it means reproducing it through unnatural means and transforming elements of the natural world to fit our human-built world. Humans interact with nature in many ways and our actions can have a negative impact on it. It’s important to understand that humans aren’t perfect and how they replicate nature can often be problematic. However, it is important that we stay connected to nature and strive to represent it truthfully while trying our best to preserve it.