[Last modified: March, 24 2019 02:56 PM]

If it be in a gravestone, a photograph or a history book; it is a human condition to want to be remembered after death. Images are created of the dead, as this allows for a historical memory of them to be recorded, as well as establishes a spiritual continuum between death, life and the present and the past. The variety of ways, including the iconographies and materials, that these images are propagated in society create different meanings to individuals as to how the deceased are portrayed. The actual reproduction of these images then have political and economic dimensions in society.

Overcoming Loss

Namgis Mask

Origin: Kwakiult tribe (Northwest Canadian Coast), ca 1919.

Location: British Museum, AM1944,02.146

Proportions: 80 x 70 cm

Materials: painted cedar wood and leather

Description: This masks represents a Crest, say an ancestral member of the Tribe, remembered for his influence. The mask has a performative function: it was used in ceremonies and rites, in order to reinforce the relationship between the living and the dead, and use the spiritual power of the ancestors to ensure good fortune to the group. This precise piece might be related to the sea and its resources.

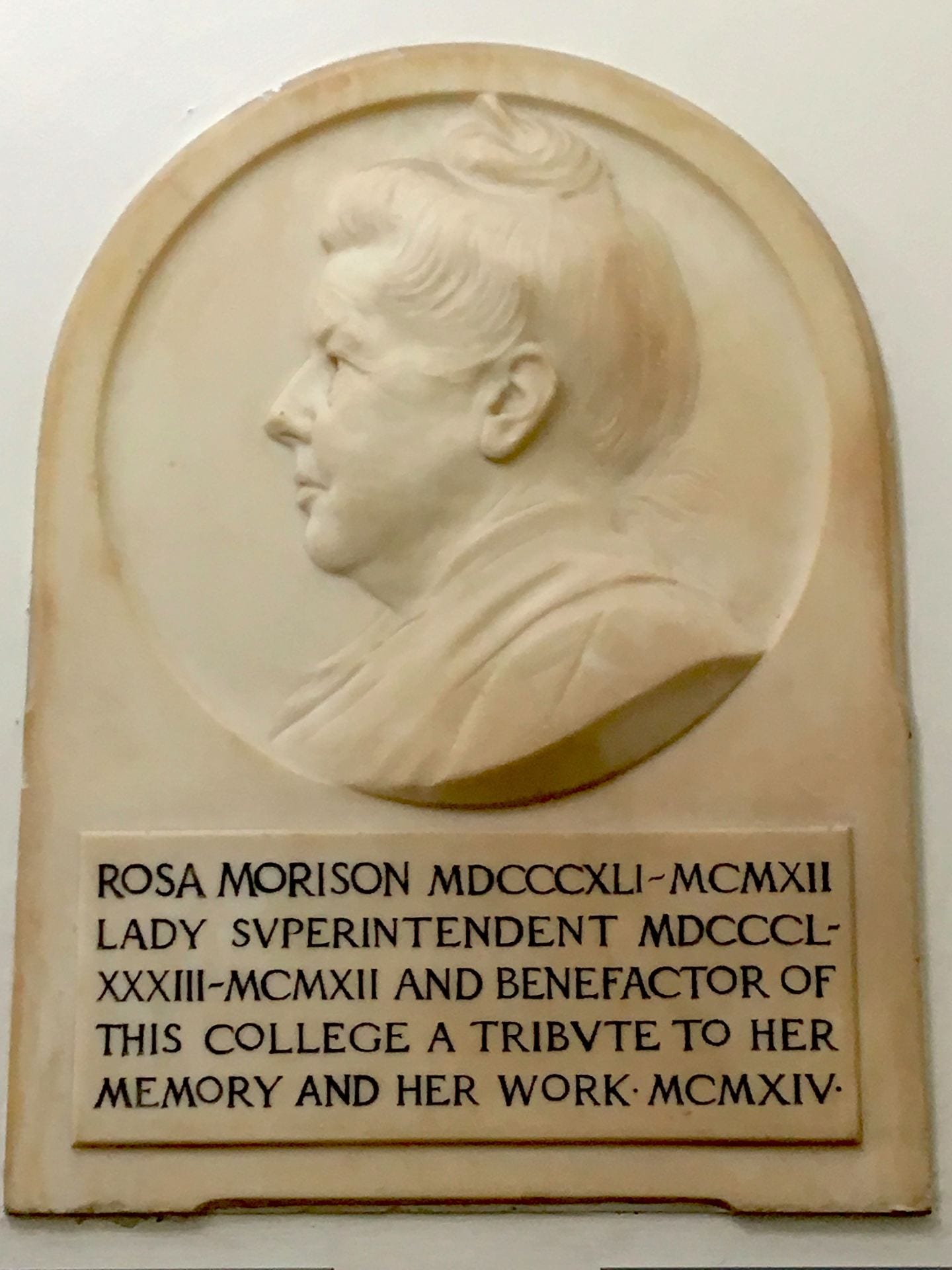

In anthropology, images of the dead have a ritual dimension: by materially reenacting the spiritual presence of the person, these objects allow us to compensate the loss and perform our process of surrogation. Memorial plaques and monuments such as this one are generally placed in public spaces and buildings; they are not self-reflective pieces, but works directly addressed to the public, statements in the open about memory and its politics. Rosa Morison’s plaque was unveiled in 1914 in the UCL hall. Placed above the heads in this common space, next to the entrance of the library, it celebrates the process of transmission of knowledge, by creating an organic interaction between the building, the students and the memory of the dead. In secular European countries, images of the dead do not carry magical meanings, like they usually do in animist societies, but they carry meanings that question the relation between history and memory.

Physical and Moral Continuation?

Memorial plaque to Rosa Morison

Date: 1914

Artist: James Havard Thomas (1854-1921),

Material: Marble tablet with medallion

Dimensions: 25 x 18,5 inches

Collection: UCL Museum of Arts.

Description: A supporter of women rights to vote and access a university education, Rosa Morrison (1841-1912) is commemorated in this plaque for her work in UCL as lady superintendent of studies and vice-principalship of dormitory for female students. The plaque shows her in an antic fashion, in order to emphasize her moral dignity : the mature profile, Roman letters and marble medallion (or Tondo) refer to the iconography of classical sculptures and cameos.

The choice of the material used for the piece is no hazard: stones generally symbolize strength and continuation. White marble, specifically, represents eternity and purity because of its smooth crystalline structure and association with the classical ideal of fine arts: for non-veined white shades (such as the one used for Rosa Morison), the main deposits are in the Mediterranean world: Carrara, Paros… The symbolism of the material in intertwined with its economic significance: marble is an expensive stone, and marble portraits underline the value of both the object and model. Furthermore, tomb and memorial sculptures are only images of the dead: they visually capture a moment or an aspect of life, in a motionless, and therefore incomplete way. We have to remember that images are interpretations of reality, and that portraits carry layers of meaning. An interesting parallel can be drawn between the portrait of Rosa Morison and the tomb sculpture of Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey, in terms of visual culture, and because both of them are official images, impregnated with the moral features of their model.

Spreading Images: Reproduction, Economy and Power

Tomb effigy of Queen Elizabeth I

Date: 1606

Artist: Maximilian Colt

Material: White marble partly painted with gold leaf

Collection: Westminster Abbey, London

Description: commissionned by King James I in 1606, this tomb effigy replaced a deteriorating wooden one when the Elizabeth’s tomb, along with that of her half-sister Mary I, were moved to a new part of the abbey. The sculpture shows Elizabeth as a woman of power, dignified in death: the shape of her body is reduced to abstract lines, and the regalia underline her power as a sovereign. Elizabeth was a much beloved monarch, associated with a new Golden Age of England, in both artistic and political terms. By patronizing this effigy of a previous monarch from another dynasty (the Tudor), James I would have paid tribute to the Queen, while showing the symbolic continuity with the new Stuart era.

As women of power, both of them are represented with tightly tied hair, a symbol of self-constraint and restrained femininity. The figures are severe, and the body animated by a hieratic tension that recalls the rigidity of death and images. Elizabeth is depicted holding the regalia, and wearing a richly ornamented dress. Although 69 and physically diminished by the time of her death, she is represented here younger, with stylised curves, according to the official imagery of her reign: the Queen was to be shown as a radiant political leader and semi-mystical figure. On the other side, Rosa Morison is only celebrated in the plaque for her work at UCL, not her commitment to women rights. Both sculptures are standardised images meant to be reproduced or disseminated. John Havard Thomas also produced a bronze cast of Morison’s plaque, hung in the student hall, and small replicas were made available to buy for UCL colleagues. The reproduction of images of the dead has a political dimension: who is worth remembering? Who has the power of agency and chooses what to remember? There is also an economic dimension to those images: for academic sculptors such as Havard Thomas, the production of those standardised plaques counterbalanced more creative works, and were a way to make a stable living.

Go further with the Namgis Mask

Watch this interesting podcast about animism and the role of death in society.

Go further with Rosa Morison

Watch this interesting podcast about gender and discrimination in the Victorian era

Go further with Elizabeth I

Watch this interesting documentary abouth royal iconography and symbolism in the late Elizabethan era

To read more about tomb sculpture and reproduction of images of the dead

Erwin Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture: Four lectures on its changing aspects from Ancient Egypt to Bernini (New York, Abrams Books, 1992)

Accessible through UCL