Read time: 7 minutes

In this blog post, Jessica Xie (final year UCL medical student) explains the ins-and-outs of out-of-hours shifts and how to be smart with your time.

As a clinical medical student, you are expected to be in clinical practice from 9am – 5pm Monday to Friday (except for Wednesday afternoons. Hooray for RUMS Sports!). This makes any time spent on placement outside of these hours (i.e nights and weekends), an out-of-hours shift. Night shifts are typically 8pm – 8am. Weekends are typically 8am – 8pm.

At UCL Medical School, the number of mandatory out-of-hours shifts depends on your year of study (e.g. in your final year, you are required to complete two night shifts and one weekend shift across the whole academic year).

You’re probably thinking, doing night and weekend shifts in hospital sounds awful… why would anyone want to? There are, in fact, many advantages of undertaking out-of-hours shifts, both for your learning and for gaining first-hand experience of what life as a Foundation Doctor/ Internal Medical Trainee/ Specialty Trainee will be like. Also, some students enjoy these experiences so much that they voluntarily attend more shifts than required.

Why Out-of-Hour Shifts Aren’t As Bad As You Think

Opportunities, opportunities, opportunities

You’ll spend most of your time on out-of-hours shifts shadowing whoever is holding the bleep (junior doctors, SHO, registrar or consultant). These are excellent learning opportunities… you can attend to emergencies as they arise and, depending on the specialty, this include going into theatre to assist. For example, I assisted in a Caesarean section at 2am. I was also allowed to suture. This was a great learning experience and something that I may never get to experience again.

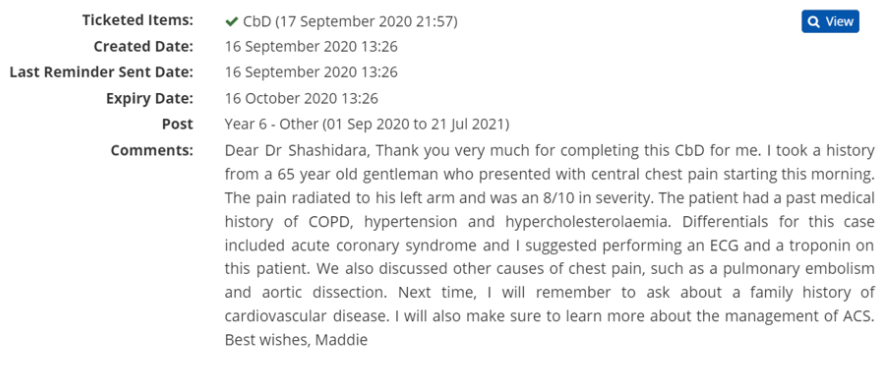

Out-of-hours shifts tend to be excellent opportunities to get procedures signed off and for Supervised Learning Events (SLEs) – watch out for a post by Maddie on how to ACE these assessments!

The ‘Junior Doctor’ Experience

With a smaller team working on nights and weekends, you’ll have more opportunities to ‘think like a doctor, act like a doctor’, with particular emphasis on the latter!

These are exciting opportunities to really develop your clinical judgement and skills. You may realise that you are more competent than you think you are, which will always give you a nice confidence boost!

However, you must of course only do things within the limits of your competency and follow all the usual rules, like gaining full consent from patients and ensuring that a chaperone is present for intimate examinations.

A Step-by-Step Guide

-

- Preparation

Pack a meal, snacks to pop into your pockets and plenty of fluids.

Similar to my advice for prepping for ward rounds, write down what you want to achieve by the end of the shift.

What to bring with you:

-

-

- Stethoscope

- Black pen

- Notebook or tablet/ iPad

- Handover sheet from handover meeting

- Mobile phone – put on silent and I recommend you to download a few of these apps:

- BNF

- Microguide

- UpToDate

- MDCalc

If you know which doctors will be doing the shift, you may want to let them know in advance that you will be joining them.

2. Attend handover

Who’s who?

Introduce yourself to the team. Ask to shadow a doctor(s) and explain to them what you would like to achieve by the end of the shift (e.g. SLE, practice a specific examination).

Exchange contact details (usually a mobile number) with your supervising doctor and make a note of the name of which doctors are holding bleeps, their bleep number and ensure that you know how to bleep. Some doctors create a Whatsapp group for the shift.

Know the schedule

Some shifts have specific times for various members of the team to take breaks… and ensure that you take one, too! It is really important that you take care of your wellbeing. Ensure that you stay hydrated. If there’s an opportunity and place for you to rest or nap, I strongly recommend that you do!

There may be a mid-shift meeting at around 2am. You should attend this. It allows the whole team to get their bearings, identify which tasks still need to be completed and delegate the work appropriately. This is a great opportunity for you to jump in and offer to help out and/or ask to shadow a different member of the team.

3. Make the most of the shift

Same as for a ward round, you should aim to help the team as best as you can.

I recommend that you ‘follow’ a patient through from when they present to the hospital, to their admission as an in-patient or discharge:

-

-

- When in A&E or AMU, clerk patients as they are admitted

- Present to the doctor

- Ask the nurses if you could take the patient’s observations

- Perform bedside investigations, like urinalysis and an ECG

- Perform clinical procedures, like venepuncture

- Order investigations on the computer

- SBAR handover to the team who will admit the patient onto their ward or write a discharge summary

- And at each step, ensure to check that your supervising doctor is happy for you to proceed

Be proactive

Seek learning opportunities, ask patients and healthcare staff questions about anything that you’re unsure about and attend to emergencies as they arise.

4. After the shift

Congratulations! You’ve completed your first out-of-hours shift!

Take a moment to reflect on your experience: What did you learn? What did you do that made you proud of yourself? What are you hoping to achieve next?

Finally, if you have completed any procedures or examinations that require a sign off, make sure you contact the relevant person(s) for their email address(es).

Being Realistic

I’ve explained above why out-of-hours shifts are not to be feared, but let’s be realistic: out-of-hour shifts can be tough; twelve-hour-long shifts can be pretty draining. After completing a night shift or two, take the next morning or day off to reset your body clock. So don’t schedule a night shift the day before compulsory teaching! If you know that you will miss teaching, politely notify your tutor or the doctor in advance.

Also, despite your best efforts to maximise outputs, you may not achieve the goals that you intended to, especially if the shift is quieter than you expected. If this does happen, don’t be too disheartened or surprised if your supervising team suggests that you head off home a couple of hours early; you’ve gained a new experience and that’s what’s important.

Top Tips

To summarise, here are my top tips to surviving out-of-hours shifts:

- Plan ahead to ensure that you are physically and mentally prepared for the shift.

- Look after yourself – when you’re clerking in a patient at one moment, then assisting in theatre in the next, it’s easy to forget to take breaks! Remember: you need to look after yourself before you can look after your patients.

Thanks for making it to the end of this post! I hope I’ve managed to convince you that out-of-hours shifts can be excellent learning opportunities if you come prepared and know what you want to achieve. If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out to any of us.

Good luck,

Jess