Reposted from the Digital Education Team blog.

Over the last two years UCL has made major strides in its use, support and understanding of digital assessment at scale. Prior to the pandemic there had been interest in providing a centrally-managed environment for exams and other assessment type. Covid accelerated these plans resulting in the procurement of the AssessmentUCL platform. The move to digital assessments brings many benefits for users (as evidenced by Jisc and others). Students can be assessed in an environment they are increasingly comfortable with; there are administration benefits, for example through system integrations and streamlined processes; and, pedagogically, digital assessments allow us to experiment with diverse, authentic, ways to appraise, and contribute to, learning.

However, at their core, digital assessment environments consist of a set of tools and technologies which can be used well or badly. In a recent Blog post, ‘Are digital assessments bad?’ I discussed many of the reservations people have about their use including issues related to digital equity, technology limitations and academic misconduct. My conclusion was that “these issues are not insignificant, but all of them, perhaps with the exception of a preference for offline, are surmountable. The solutions are complex and require resource and commitment from institutions. They also require a change management approach that recognises both the importance of these issues, and how they impact on individuals. It would be a massive fail to brush them under the carpet.” We in the Digital Assessment Team stand by this conclusion. The move to online assessment during Covid has surfaced a lot of pre-existing issues with ‘traditional’ assessment as identified by Sally Brown and Kay Sambell, and others.

In this post I’d like to look at one of the identified problem areas: Academic integrity. I want to consider the relationship between digital assessments and academic integrity, and then put forward some ideas that could better support academic integrity. Is the solution removing digital assessments and insisting on in-person handwritten exams? Or if it is something more complex and nuanced, like creating the right institutional environment to support academic integrity.

A very brief history of cheating

Cheating in assessments has been around since the origin of assessments. We can all remember fellow students who wrote on their arms, or stored items in their calculator memory. The reddit Museum of Cheating shares cheating stories and images from old Chinese dynasties to the present day. However, the move to digital assessments and online exams has not only shone a light on existing misconduct, but also presented new possibilities for collusion and cheating. Figures vary across the sector but one dramatic poll by Alpha Academic Appeal found that 1 in 6 students have cheated over the last year, most of whom were not caught by their institution. And “almost 8 out 10 believed that it was easier to cheat in online exams than in exam halls”. Clearly this is not acceptable. If we cannot ensure that our degree standards are being upheld this devalues both the Higher Education sector and the qualifications awarded.

We need to begin by accepting that issues exist, as is often the case with any technological progress. For example, think about online banking. It brings many benefits but also challenges as we adapt to online scams and fraud. Artificial Intelligence (AI) adds additional complexity to this picture. Deep learning tools such GPT-3 now have the power to write original text that can fool plagiarism checking software, but AI can also support streamline marking processes and personalise learning.

A multi-faceted, multi-stakeholder approach

So what is the answer? Is it moving all students back to in-person assessments and reinstating the sort of exams that we were running previously? Will this ensure that we create exceptional UCL graduates ready to deal with the challenges of the world we live in? Will it prevent all forms of cheating?

UCL has heavily invested in a digital assessment platform and digital assessment approaches. How can we take the learning from the pandemic and the progress we have made in digital provision and build on that for the benefit of students and the university. See Peter Bryant’s recent post ‘…and the way that it ends is that the way it began’. While there are some cases where in-person assessment may be the best option temporarily, long-term we actually hope to take a more progressive and future-proof approach. This requires an institutional conversation around our assessment approaches and how our awards remain relevant and sustainable in an ever-uncertain environment. If we are to stand by our commitments to an inclusive, accessible, developmental and rewarding learning experience for students, will this be achieved by returning to ‘traditional’ practice? How can we support staff by managing workload and processes so that they can focus on learning and assessment that make a difference to students? Changing an institutional environment or culture isn’t a straightforward process. It encompasses many ideas and methods, and requires a multi-stakeholder commitment.

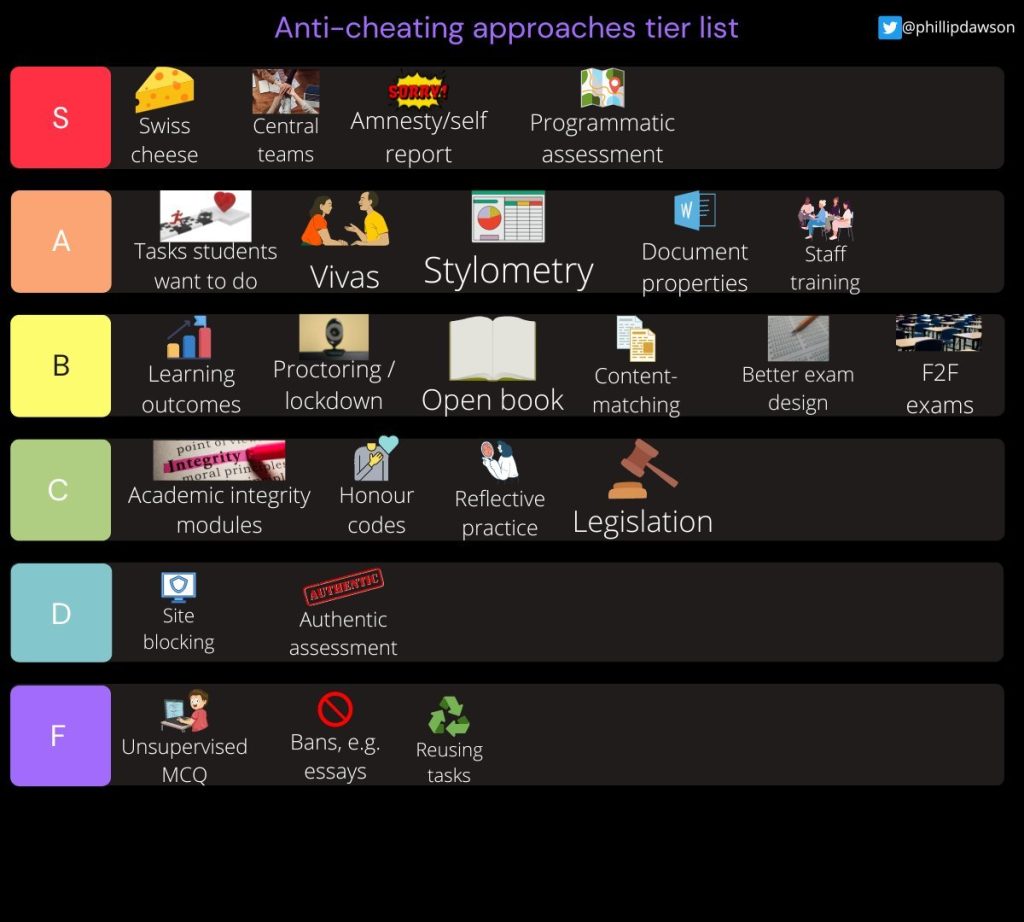

Within the Digital Assessment Team we have begun to look to Phill Dawson’s academic integrity tiers list for reference. Phill Dawson is Associate Director of the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning at Deakin University in Australia. In his tier list exercise Phil is asking the question about assessment priorities. If the priority is academic integrity /preventing cheating what strategies will enable you to achieve this? He often talks about an anti-cheating methodology that involves multiple approaches (the Swiss cheese approach), with programmatic assessment, central teams and student amnesties being the most effective mechanisms.

For reference Tier lists are a popular online classification system usually used to rank video games characters. Their adoption has increasingly extended to other areas including education. Within the tier system S stands for ‘superb’, or the best, A-F are the next levels in decreasing value. You can see the full explanation of Phill Dawson’s tier list along with research to justify his placement of activities in his HERDSA keynote talk.

A possible UCL approach?

At UCL we are already undertaking many of these approaches and more in order to build an institutional environment that increases academic integrity. You could say that we have our own Swiss cheese model. Let me give you a flavour of the type of activities that are already happening.

Assessment design – I have heard it said that that you can’t design out cheating, but you can inadvertently design it in. Focusing on assessment design is the first step in building better assessments that discourage students from academic misconduct. Within UCL we are bringing together Arena, the Digital Assessment Team and others to look assessment design early in the process, often during the programme design level, or at the point a programme or module design workshop is run. The aim is diverse, engaging, well-designed assessments (formative and summative) that are connected to learning outcomes and are often authentic and reflective. The UCL Academic Integrity toolkit supports academics in this design process. We are collecting case studies on this blog.

Assessment support – We need to build student and staff capability with regard to academic integrity. We plan to rationalise and promote academic integrity resources and skills-building training for students. These resources need to give the right message to our students and be constructive, not punitive. They need to be co-developed in collaboration with faculty and students and be part of an ongoing dialogue. They also need to be accessible to our diverse student body including our international cohort who may join our institution with a different understanding of academic practice. There also needs to be well-communicated clarity around assessment expectations and requirements for students. We are supporting Arena with further training specifically for staff, for example on MCQ and rubric design, and with supporting their students in understanding this complex area. There is also scope for training on misconduct identification and reporting processes. We are also working with Arena to review Academic Integrity courses for students.

Technical approaches – There is a stated need for assessments that focus on knowledge retention in certain discipline areas, which is why we are piloting the Wiseflow lockdown browser. The pilot has three different threads: (1) a Bring Your Own Device pilot with Pharmacy; (2) a pilot using hired laptops in the ExCel Centre, likely with modules from School of European Languages, Culture and Society (SELCS); and (3) a departmental pilot using iPads in the Medical School. In parallel, the Maths Department are using Crowdmark to combine in-person assessments with digital exams. And as a team we are building up our knowledge of detection platforms. such as Turnitin and their stylometry tool draft coach, and of the use of AI in relation to assessment.

Better understanding of academic misconduct – In order to tackle academic misconduct we need to understand more about why it takes place, not in a general way but at UCL on particular modules and particular assessments, and with particular cohorts or students. Some of this information can be identified through better analysis of data. For example, one recent initiative is the redevelopment of an assessment visualisation (‘Chart’) tool, which depicts the assessment load and patterns across modules. This can help us identify choking points for students. We are also involved in a mini-project working with the student changemakers team in which we will be running a series of workshops with students looking at the area of academic integrity.

For discussion

We are unlikely to stamp out all forms of cheating, regardless of where our assessments take place. Thinking we can do this is both naïve and shortsighted.

However, we can work to creating an institutional environment where misconduct is less likely. In this environment we develop students who are well-supported and fully understand good academic practice and its benefits, for themselves as students, and the community more widely. They are able to prepare well for their assessments and are not put under unnecessary pressure that doesn’t relate to learning outcomes of their course. They are provided with well-explained, well-designed, challenging and relevant assessments that engage their interest and build capability and skills. They are supported in understanding the misconduct process and can be honest and open about their academic behaviour throughout their time at UCL. If the assessment is heavily knowledge-based, then it takes place in an environment in which access to outside resources is limited, but it is non-invasive and students are still respected and trusted throughout. An approach like this is compassionate and supports student wellbeing. It is cost effective, by reducing academic misconduct panels and the need for large-scale in-person assessments. It is progressive and scalable with useful online audit trails. It should work for academic and administrative staff. The Digital Assessment Team is committed to working with academic teams to realise this vision.

What do others think? How does such a vision support our institutional strategy and could it form part of a UCL teaching and assessment framework?