The plague is a fixture of medieval history, and conjures up images of doctors in beaked masks and X-marked front doors. The horror of living the reality was likely far greater than anything we can imagine; today’s pandemic, while admittedly mismanaged in many cases, is up against thousands of scientists and advanced healthcare protocols, which removes much (but not all) of its uncertainty and danger.

In 14th century Italy, germ theory was still a couple hundred years away, and microscopy another century after that (1). There were theories as to how it spread, through the air and bad vapors, but the real culprit, rodents, had not yet been identified. As a result, there was a spike in religious fervor, especially in Italy, as penance for the sins that had supposedly brought the disease down on humanity. Self-flagellation and religious parades became common, public ways to express devotion, leading to a variety of new social dynamics. In some cases, they were an opportunity for disputes to be settled and for solidarity to be shown (2). In others, they became destructive, violent, and headed by ambitious laymen instead of the traditional religious leaders. Today mimics it, in a way. The urgency of COVID has revealed the extremes of human existence, bringing about beautiful shows of compassion as much as acts of selfish desperation (3).

On a different note, it’s interesting to wonder what would have happened had the plague really been airborne. Would people have realized and locked themselves away in their homes? It is difficult to put ourselves into that frame of thinking, since our generation has been raised from birth with at least a very rudimentary knowledge of what a germ is, and that washing our hands and covering our mouths to cough stops us from getting sick. However, many of the strategies used in the 14th century are reasonably similar to those that make up preventative care today; exercising, eating healthy, unspoiled food, and maintaining a routine (4). These things do not necessarily require explicit scientific knowledge to understand, and the historical integration of prayer and religion would perhaps have helped solidify the average person’s routine.

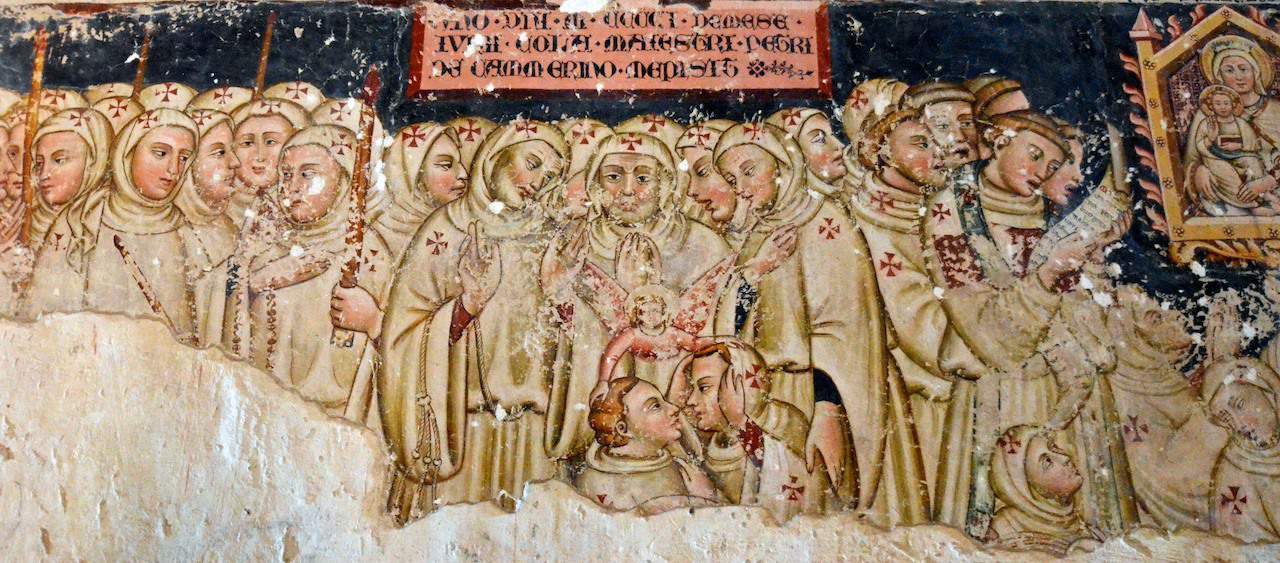

The literature and art left behind explain and depict the actions carried out in order to ward off the plague, but there are always limitations. Texts were primarily written from a highly educated point of view, which was not representative of the majority of the population in the medieval era. Art was created heavily featuring symbolism, with images of angels in processions or similarities to Jesus Christ in works concerning self-flagellation (see below).

(5) (image description: mural on a 15th century Italian church depicting an angel mediating and argument or blessing two individuals from a crowd of followers)

As a result, many pieces of art were an idealized version of what the religious acts were supposed to embody, making them a somewhat unrealistic source of information on the events of the time (5). Ultimately, however, these depictions serve to emphasize the role of religion in dealing with the plague, especially in conjunction with society’s relative helplessness to combat it from a scientific perspective.

References

- The history of germ theory in the College collections | Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh [Internet]. Rcpe.ac.uk. 2021 [cited 27 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/history-germ-theory-college-collections

- Horrox R. The Black death. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 1994.

- Meyersohn N. Cops in the toilet paper aisle: Grocery stores add extra security [Internet]. CNN. 2021 [cited 27 January 2021]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/23/business/grocery-stores-coronavirus-security/index.html

- DURAN-REYNALS M, WINSLOW C. REGIMENT DE PRESERV ACIO A EPIDIMIA O PESTILENCIA E MORTALDATS. Bulletin of the History of Medicine [Internet]. 1949;23(1):57-89. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44443424

- di Camerino C. Vallo di Nera: Church of Santa Maria; 1401.