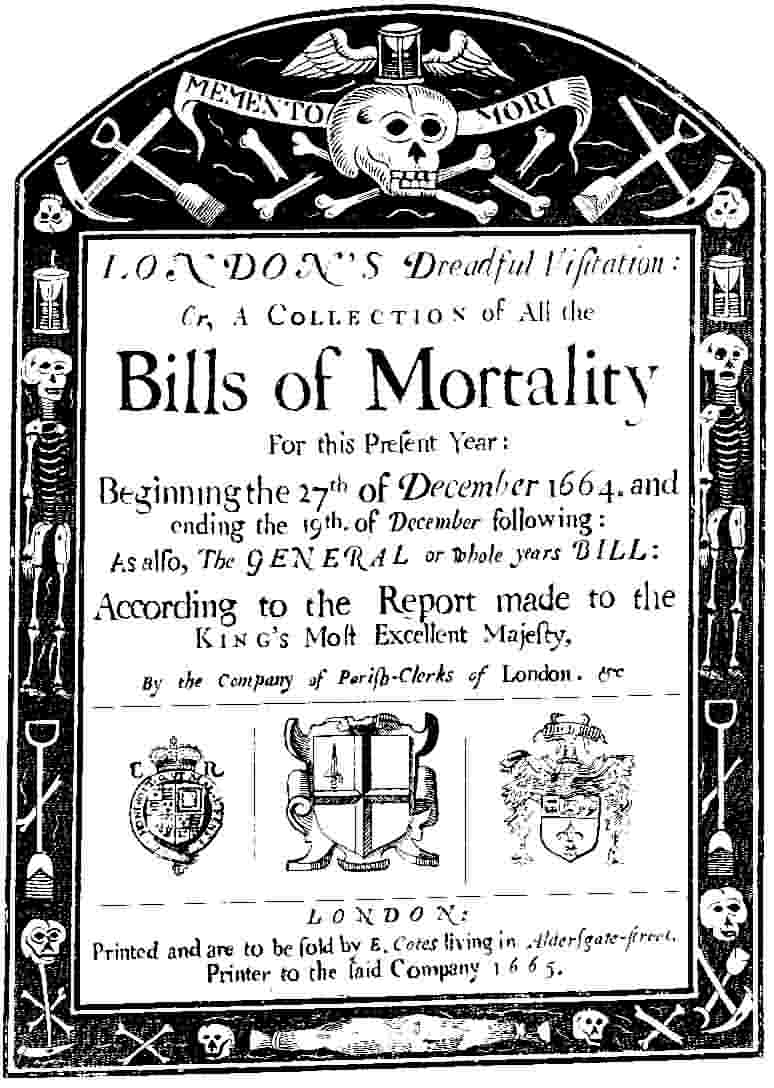

Daniel Defoe’s “Journal of a Plague Year” is an intriguing piece of fiction for several reasons. To start, while it was published in 1722 and therefore counts as a historical source for us, it was also a piece of historical fiction when it was published, given that the event chronicled occurred half a century before (1). According to Professor John Mullan, its existence marked the beginning of the genre of “novel,” but the religious slant we see throughout the work is the closest we come to seeing a non-factual bias from Defoe. It was published under a pseudonym as a genuine account of the plague outbreak that killed tens, even hundreds, of thousands in London and the surrounding areas, and Defoe pulls his authenticity from the use of the very real and jarringly objective Bills of Mortality, which he cites throughout the work as the narrator HF watches his corner of the city crumble before his eyes (2).

(3)

The Bills of Mortality themselves are an impressive feat. Realistically, collecting the information would not have been overly difficult, but compared to the Medieval period, with its vague and heavenly artwork, the official data collection from every parish coupled with printing and copying capability was a significant and helpful shift in human advancement. However, medical knowledge continued to trail behind, giving rise to similar mentalities that spurred the rise of the Bianchi. Self-flagellation may have been out of style in the 17th century, but HF notes that several of the more religious families observed periods of fasting to appease the heavens. For the masses, rather than dramatic processions, con-men rose out of the shadows, promising expensive cures and talismen to cure the sickness or keep it away altogether. Perhaps they knew that if their customers died, they wouldn’t be held accountable anyway. Regardless, the desperation after seeing so many drop dead forced people to try what they could in hopes of avoiding acquaintance their local mass grave.

The mass graves were certainly real, though Defoe’s exact account of it must have been fictional. His commitment to the factuality of the year, and the interviews and research he must have done to construct such novel are truly impressive. Though accounts of specific people may have been embellished or created, like the one of a man watching the bodies of his whole family be tossed into a mass grave, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that events transpired similarly in real life. His pride in London certainly seems to be real, with the quote “it was never to be said of London, that the living were not able to bury the Dead. (4)” This is quite a broad statement that is not plague-specific, but maybe more humanity-specific. After so many pages of death and horror, it re-sensitizes the reader to mortality and a continued sense of community in the city.

The process of writing an accurate fictional work about a real event removes the bias of a single real person experiencing it, instead replacing it with the observations of many. Defoe’s foray into a new form of literature is appropriately marked by choosing a topic as significant as London’s plague.

References

- Kavanagh D. Daniel Defoe: A Journal of the Plague Year [Internet]. London Fictions. 2020 [cited 1 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.londonfictions.com/daniel-defoe-a-journal-of-the-plague-year.html#

- Jordison S. A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is our reading group book for May [Internet]. the Guardian. 2020 [cited 1 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2020/apr/28/a-journal-of-the-plague-year-by-daniel-defoe-is-our-reading-group-book-for-may

- Company of Parish-Clerks of London, 1665. Bills of Mortality. London.

- Defoe D. A Journal of the Plague Year. 1st ed. New York: E. Nutt; 1722.