Among the many historical and modern definitions of the word ‘crisis’, its original ancient Greek definition remains relevant today, as a turning-point where the community must come together to decide what to do next (1). We have seen plenty of that during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in its early days, and because of its ability to affect anyone, especially the elderly, society responded to it on a massive scale. People came together to make masks, provide food for children, and generally embody the neighbourly sense of codependence that we have apparently been losing. However, it was specifically its ability to affect everyone that caused such a large-scale mobilization of resources and regulations. Other crises that disproportionately affect minorities and powerless groups have the tendency to be disregarded, and as a result, exclusion within crisis situations means that the egalitarian feeling of citizens banding together to defeat a joint problem is perhaps over-exaggerated.

(2)(description: nurses wearing volunteer-made fabric masks due to PPE shortage)

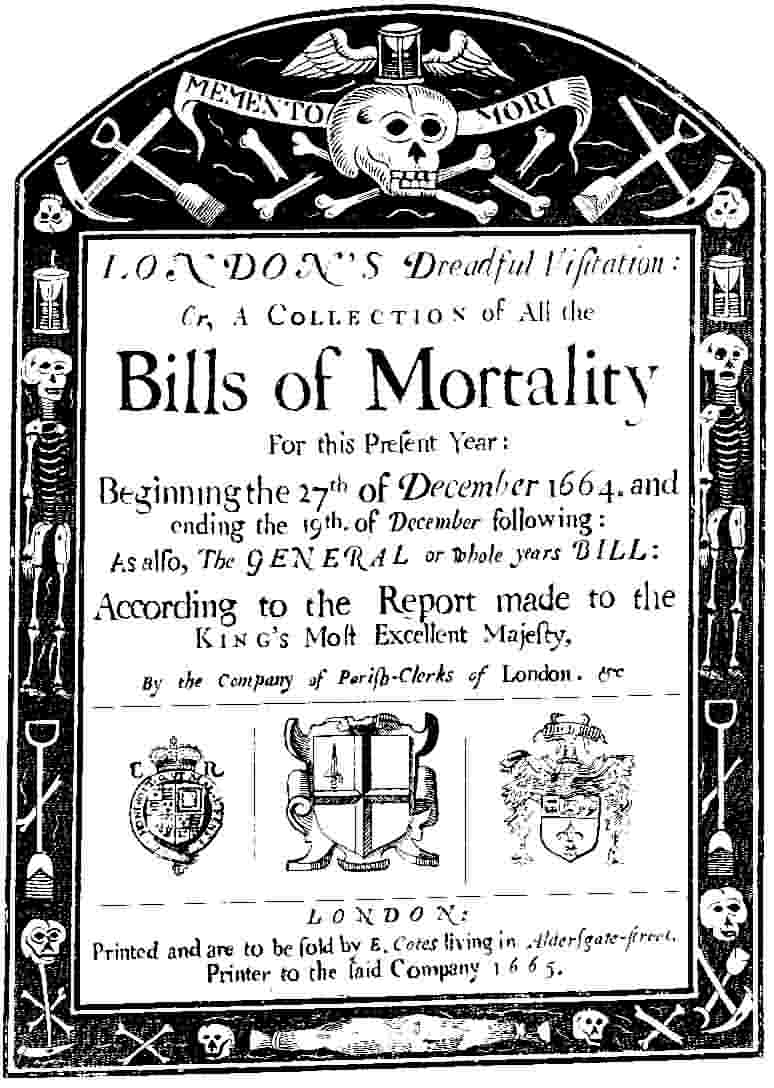

Daniel Defoe’s “Journal of a Plague Year” is an intriguing piece of fiction. Its accounts of all the different individuals who would have passed through Defoe’s corner of London give a varied and exciting depiction of the hustle and bustle within one of Europe’s most important cities. The narrator, HF, mentions the rich (himself included) having the option to flee to their houses in the countryside to escape the plague, while the poor would perish along the roads after being denied entry to every town they came upon, and when infected with the plague, were too weak to drag themselves to find food. Some benefactors would leave bread in fields at a safe distance, but even still, thousands perished out there. They were also targeted by con-men promising expensive cures and talismans to cure the sickness or keep it away altogether; perhaps they knew that if their customers died, they wouldn’t be held accountable anyway. The religious convinced themselves that the plague was God’s wrath, and would endure periods of extended fasting to protect themselves (3).

The variety calls attention to the role of class privilege within crisis. The poor could not feed themselves and often found themselves at the mercy of those looking to make a quick buck, while the middle-class had the privilege of choosing not to eat as a preventative measure. As expected, the rich simply left. In a universal crisis such as one caused by disease, yes, “we’re all in the same boat,” but poverty adds a completely separate layer to the struggle of survival. Exclusion of those without economic privilege in modern crisis narratives is a privilege in and of itself, because a stay-at-home order might be frustrating for all of us, but having to balance it with also being unable to pay rent invalidates the sentiment of a communal struggle that so many corporations and celebrities have enjoyed propagating.

It gets worse when the crisis in question doesn’t affect everyone. The 1980’s HIV crisis’s struggle for widespread acknowledgement seemed to come down to two primary factors, the first being general homophobia (4). The general public’s designation of gay people (especially men) as deviants, meant that a disease more common in gay men at the time wasn’t overly successful in garnering sympathy from the wider population (5). While that stigma still exists today, it is greatly diminished, especially in Western nations with more liberal ideologies. Additionally, ongoing HIV/AIDS education campaigns about transmission and harm reduction have been successful over the years, and information is now included in most science-based adolescent sex education (6).

The other factor is the minority status of the group most affected. Being openly “out” was less common than it is today, which was understandable given the increased risk of experiencing hate crimes and professional discrimination (5). A small population of activists may have been working to demonstrate HIV’s risks to everyone, including through asexual transmission, but strength in numbers was lacking. To many, HIV still did not affect them to a significant degree, and thus the HIV crisis was excluded from the same level of urgency afforded to problems affecting a larger population.

This ties into the question of public health: how do we approach it with limited resources? There is an ongoing debate about whether it should be dealt with from an individual point of view or by looking at the benefits to the wider population, but regardless of institutional organisation, under no circumstance should care be based on whether the individual is part of an accepted group (7). In that case, it ceases to be a concern of allocation of rights, or obligation to provide rights, and instead becomes a direct attack on individual freedom and equality.

The issue of exclusion extends even deeper when an issue affects a non-minority group but is still unrecognized as being widespread, the most evident example of this being sex discrimination. We have progressed in leaps and bounds since the days of erasure and inaccurate canons of the female role in art, science, and politics, but as demonstrated by Caroline Criado-Perez’s Invisible Women, there remains a multitude of barriers around the world that prevent women, both directly and indirectly, from enjoying the same benefits that society has to offer men (8).

We still have overtly misogynistic behaviour: FGM, femicide, lack of access to birth control/abortion services, and the prevalent dichotomy of female slut-shaming versus the acceptance and even celebration of male sexual prowess (9). It’s the hidden barriers, however, that Invisible Women seeks to deconstruct. It’s the things that are unintentional results of a world where male-centric behaviours are so normalized that the insinuation of inequality sounds radical and disruptive, that walk the fine line between being brave feminism and a whiny “feminazism” (a term popularized in 1992 by conservative radio host Riush Limbaugh) (10). The notion that women should be allowed to work, vote, and own property is no longer so controversial in the West, but proposing the allocation of money to research male-centric public transport infrastructure? Not so easy. The bias is undoubtedly there when you look at the numbers, but 1) a lot of people don’t have the training to understand the data (thankfully Criado-Perez is an excellent explainer), 2) it’s hard to genuinely portray the issue in an clickbait headline, and 3) in many cases, the data simply doesn’t exist, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s easier to omit gender-segregated data, but without it, there’s no proof that unintentional discrimination is occuring. The field of city planning is beginning to acknowledge it, but the revamp of said infrastructure is unlikely to be a quick process (8).

While crisis can be adequately, and even universally, defined, there is no universal way to solve it, because the range of situations that crisis encompasses is broad to the point that it has been argued that the entirety of human existence has had a crisis of some sort occurring. However, drawing attention to the exclusion of underprivileged or underrepresented groups is essential in order to fully embody one of the only positive aspects of a crisis: communal and democratic effort. Crises should not be praised for having the silver lining of bringing everyone together if not everyone is brought together. We have seen incredible feats of teamwork and compassion across the world in the last year, but as long as inequality exists in the absence of a crisis, it will persist within crisis situations as well.

References

- Koselleck R. Kritik und Krise. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta;.

- Collins J. Volunteers rally to produce homemade face masks for coronavirus medical workers – Orange County Register [Internet]. Ocregister.com. 2021 [cited 26 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.ocregister.com/2020/03/25/volunteers-rally-to-produce-homemade-face-masks-for-coronavirus-medical-workers/

- De Foe D. A journal of the plague year. London: E. Nutt; 1722.

- Morris B. History of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Social Movements [Internet]. https://www.apa.org. 2021 [cited 26 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/history

- Anthony A. ‘We were so scared’: Four people who faced the horror of Aids in the 80s [Internet]. the Guardian. 2021 [cited 26 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jan/31/we-were-so-scared-four-people-who-faced-the-horror-of-aids-in-the-80s

- History of HIV and AIDS overview [Internet]. Avert. 2021 [cited 26 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/history-hiv-aids/overview

- O’NEILL O. The dark side of human rights. International Affairs [Internet]. 2005;81(2):427-439. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3568897?seq=1

- Criado-Perez C. Invisible women. London: Chatto and Windus; 2019.

- Endendijk J, van Baar A, Deković M. He is a Stud, She is a Slut! A Meta-Analysis on the Continued Existence of Sexual Double Standards. Personality and Social Psychology Review [Internet]. 2019 [cited 25 March 2021];24(2):163-190. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7153231/

- Hesse M. Rush Limbaugh had a lot to say about feminism. Women learned how to not care. [Internet]. Washington Post. 2021 [cited 25 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/rush-limbaugh-feminism-feminazis/2021/02/19/3a00f852-7202-11eb-85fa-e0ccb3660358_story.html