"Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures."

– Jessamyn West

When thinking about the word fiction, the first thing that comes into one’s mind might be words on the lines of fantasy, fabrication, and creative writing. Nevertheless, such association between fiction and fantasy is suggested to be inaccurate for various works of fiction (1). Both the reflection theory and the social control theory provides the concept of an evident relationship between works of fiction with the societal reality in the time period the fiction was written in.

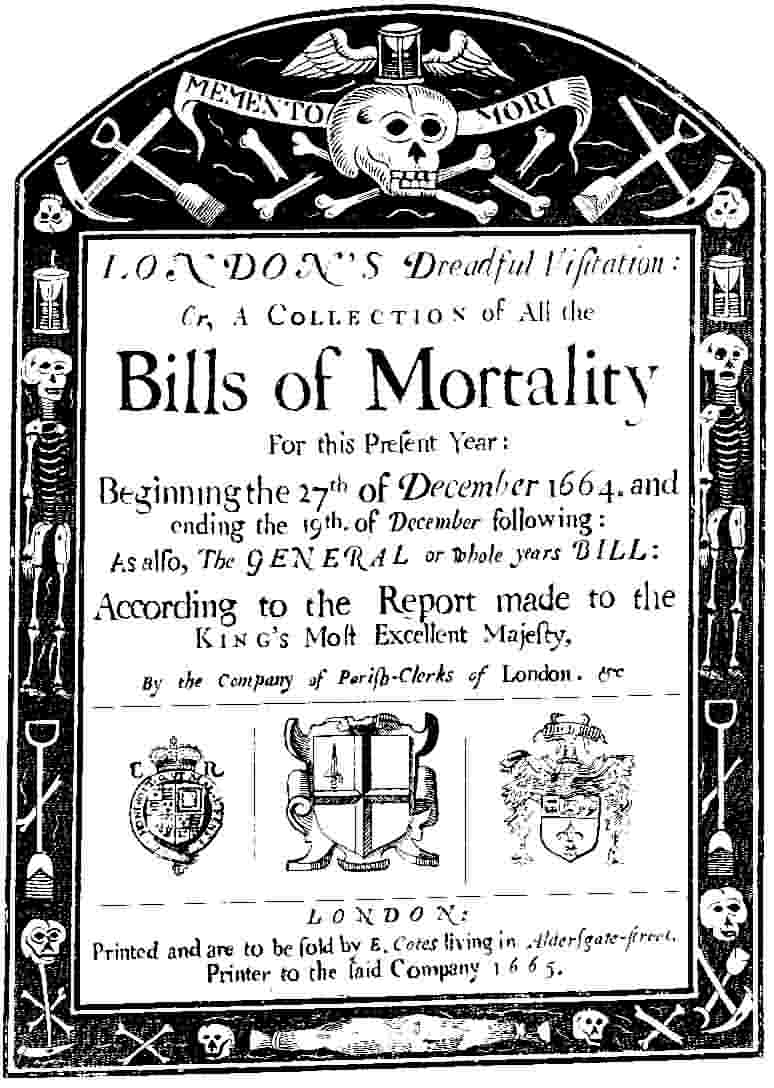

The reflection theory suggests the view of literary works as a tool in reflecting the social phenomenon within a given time period (1) . A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is an example of literary works, specifically a fiction work, that reflects the social phenomenon during the bubonic plague in 1665 London. The novel is written as an account of the narrator’s experience and lies between the borderline of fiction and reality with its use of factual evidence and detailed recounts from individual characters within the novel (2). The uses of descriptions such as ‘removing the dead Bodies by Carts’, and ‘the living were not able to bury the dead'(3) illustrates virtual imagery of hopelessness of humanity against nature as the number of the deceased gradually increase and outnumbering the number of people alive in London with no signs of stopping. This illustration of hopelessness is further strengthened in Defoe’s description of the death of ‘a maiden’ and her mother, where on the discovery of her child’s symptoms of the plague the mother ‘fainted first, … then ran all over the house, …and continued screeching and crying out for several Hours, void of all Sense.'(3). The detailed account of the mother’s actions presented to the readers the immense amount of pain the mother or any individuals at the time felt when discovering their loved ones was doomed by the plague. This sense of hopelessness and pain targets the reader’s empathy towards the characters and presents horrifying but real imagery of the society within the bubonic plague during 1665 London. Such emotions of individuals in the time is often obscured by the reality as numerical values shown in the forms of death accounts demonstrates little about the emotions of the deceased and the impact of their death on their close relatives.

In addition to the reflection theory, the social theory suggests fiction plays an active role in shaping human societies through revealing the truth at a given time period (1). Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House is an example of a work of fiction that reveals the truth of the position of women in a patriarchal society and created controversial thoughts on the roles of women and men within the Norwegian societies since its premier in 1879 (4). The continuous metaphor of the protagonist, Nora the housewife of Torvald, with small fragile animals such as “little songbird”, “squirrel” and “skylark”(5) symbolises the position of women during 19th century Norway as creatures that require the protection of their male counterparts. The climax of the novel where Nora “slamming”(5) the door on her husband and family at the end of the play suggests the release of long-oppressed emotions of women at the time. These illustrations of Nora’s position within the Norwegian society prior and in the 19th century demonstrates the truth of the circumstance of all married women as they remain under the guardianship of their husband until 1888 (6). Furthermore, the creation of fiction characters based on the positions of married women in reality, allowed Ibsen to express the emotions of married women in 19th century Norway.

Through the description of the emotions of individual personals, fictions reveal additional truths within a period of time that reality presented through numerical values and emotionless reports obscures.

Reference list

- Inglis, Ruth A. “An Objective Approach to the Relationship Between Fiction and Society.”American Sociological Review, vol. 3, no. 4, 1938, pp. 526–533. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2083900. Accessed 1 Feb. 2021.

- Mayer, Robert. “The Reception of a Journal of the Plague Year and the Nexus of Fiction and History in the Novel.”ELH, vol. 57, no. 3, 1990, pp. 529–555. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2873233. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

- Defoe Daniel. “ A Journal of the Plague Year.”E.Nutt at the Royal – Exchange; J. Roberts in Warwick-lane; A. Dodd without Temple-Bar; and J.Graves in St. Jame’s – street. 1722

- “Henrik Ibsen : A Doll’s House”, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2001 Norway, http://www.unesco.org/new/en/henrik-ibsen-a-dolls-house/

- Henrik Ibsen, “A Doll’s House”, translated by Peter Watts, PenGuin Books, 1965

- Heffermehl, Karin Bruzelius. “The Status of Women in Norway.”The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 20, no. 4, 1972, pp. 630–646. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/839034. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.