Plenty of people have offered examples of some of the weird nonsense ChatGPT and other AI text generators have been spewing recently, but I am not convinced everyone is able to fully appreciate how this odd mix of truths, half truths and utter claptrap may be more hindrance (especially in the immediate future) than blessing for anyone looking for an easy shortcut for written assignments (or written anything to be honest!) Whilst I have found ChatGPT remarkable in some ways, such as baseline planning, idea generation, synthesis of given text or re-formatting as can be seen in this sandpit , the big fear, the supposed ‘death of the essay’, is a long way off*. ChatGPT generates some great ideas for essay titles, a decent enough standard marking rubric and some workable boilerplate feedback but it’s actual attempt to write those essays and then assess them against the rubric it created leads to some real generosity in interpretation of what constitutes a passing standard at undergraduate level. It does make me wonder about the actual requirements of these qualifications it could supposedly pass, to be honest. The now (sort of) familiar, anodyne but mostly grammatical offerings seem all the more plausible when you don’t already know the thing it is generating text about. So, I thought, what do I know a lot about? After considering a range of academic subjects that might make me look intellectual, I realised with Socratic clarity that my head is practically a vacuum. I decided therefore to get it to write an essay about something I might be happy to be quizzed about on Mastermind: Tottenham Hotspur’s FA Cup final wins. At school I did a presentation on this topic and, although it was longer and more boring, I’m pretty sure I got my facts right. In addition to a number of omissions (e.g. the 1967, 1981 and 1982 are finals missing), it also makes stuff up but surrounded as these things are by things that are accurate it all feels plausible. I share it below as an example of just how flawed an essay can be on oft-cited, indisputable facts.

I have emboldened some of the inaccuracies to illustrate this and [added comments if relevant in square brackets]

Prompt: Write an essay about Tottenham Hotspur’s FA cup victories, dedicating a paragraph to each one

Tottenham Hotspur is one of the most successful football clubs in the history of English football. Over the years, they have won numerous domestic and European titles, but one competition that holds a special place in the hearts of Spurs fans is the FA Cup. In this essay, I will take a look back at Tottenham Hotspur’s FA Cup victories and dedicate a paragraph to each one.

Tottenham’s first FA Cup triumph came in the 1900-01 season. After reaching the final for the first time in the club’s history, Spurs faced Sheffield United at Crystal Palace in front of a crowd of 110,820 [so far , so good, accurate crowd and venue…it’s looking good]. The game was a closely contested affair [true- it finished 2-2], but a late goal from striker Steve Bloomer [did not play, was in neither team and certainly therefore did not score] secured a 2-1 victory for Tottenham [actually the game finished 2-2. In the replay Spurs won 3-1]. The win made them the first [and only – an important omission] non-league team to lift the trophy, and it marked the beginning of a long and successful relationship between Spurs and the FA Cup.

The next FA Cup success came in 1921, when Spurs faced Wolverhampton Wanderers in the final. The match was played at Stamford Bridge, the home of Chelsea, and once again, Tottenham emerged victorious. A brace from Jimmy Dimmock and a goal from Tommy Clay [He did play but didn’t score; Jimmy Dimmock got the only goal] secured a 3-0 win for Spurs, and they lifted the FA Cup for the second time in their history.

In 1961, Tottenham won their third FA Cup, and this time, they did it in style. After cruising through the early rounds, Spurs faced Leicester City in the final at Wembley. The match is often remembered as one of the greatest FA Cup finals of all time, and it saw Tottenham emerge as 2-0 winners, thanks to goals from Bobby Smith and Terry Dyson. The victory marked the start of a golden period for the club, and they would go on to win a league and cup double the following season.

Tottenham’s fourth FA Cup triumph came in 1962, just a year after their first success. This time, they faced Burnley in the final, and the match was played in front of a crowd of 100,000 at Wembley. Once again, Spurs emerged victorious, thanks to a brace from Bobby Smith and a goal from Terry Medwin [right number of goals, wrong goalscorers]. The win made Tottenham the first club in the 20th century to win the FA Cup twice in a row [sounds very plausible but Newcastle did the same in ‘51 and ‘52- something they can only dream of now, like Spurs]

Tottenham’s most recent FA Cup triumph came in 1991, when they faced Nottingham Forest in the final. The match was played at Wembley, and Tottenham secured a 2-1 win, thanks to goals from Paul Gascoigne and Gary Lineker. The victory was particularly sweet for Spurs fans, as it marked the end of a long wait for silverware. The club had gone six years without a major trophy, and the FA Cup win was seen as a turning point for the team.

In conclusion, Tottenham Hotspur’s FA Cup victories have played an important part in the club’s history. From their first success in 1901 to their most recent triumph in 1991, the FA Cup has provided Spurs fans with countless memories and moments of joy [‘moments’ being the most painful of accurate things included]. While the club has not lifted the trophy since then, they remain one of the most successful teams in the competition’s history, and fans will always cherish the memories of those five famous victories.[what about the other 3?!]

—————–

So that’s at least 10 major factual errors and several errors by omission in only 600 words. Relying on a tool to generate text and assuming accuracy is still very much NOT the best way to use these tools (at present). Nevertheless, how long before such things are pumped out on blogs or elsewhere and become the ‘truth’? Or, better /worse still (depending on how you look at it), maybe we are at the foot of the rise on a sigmoid curve and in 6 months all this nit picking will be a laughable relic.

*and even when capabilities improve faster than you can say ‘Spurs last won the league in black and white’ I am still very much of the school of thought that thinks it is worth teaching (and/or learning) how to write an essay!

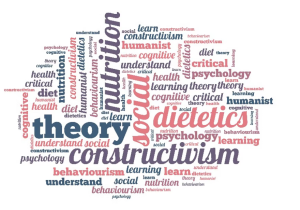

One of the problems with this is that a quick search for ‘theories of learning’ will present a dazzling, complex, sometimes-contradictory array of theories and ideas. It immediately raises several questions:

One of the problems with this is that a quick search for ‘theories of learning’ will present a dazzling, complex, sometimes-contradictory array of theories and ideas. It immediately raises several questions:

I used a number of visual hooks today in a session…it’s actually running right now (they’re in a breakout discussion)… and I asked what this swiss army knife might represent in the context of the short course they are on. One of my amazing colleagues (Most are PhD students/ PGTAs), Elizabeth, said:

I used a number of visual hooks today in a session…it’s actually running right now (they’re in a breakout discussion)… and I asked what this swiss army knife might represent in the context of the short course they are on. One of my amazing colleagues (Most are PhD students/ PGTAs), Elizabeth, said: