Guest post from Dr Alex Standen (UCL Arena). I am grateful to my colleague Alex for the post below. I can, I know, be a little bit ‘all guns blazing’ when it comes to issues of plagiarism and academic integrity because I feel that too often we start from a position of distrust and with the expectation of underhandedness. I tend therefore to neglect or struggle to deal even-handedly with situations where such things as widespread collusion have clearly occurred. It is, I accept, perhaps a little too easy to just shout ‘poor assessment design’! without considering the depth of the issues and the cultures that buttress them. This post builds on an in intervention developed and overseen by Alex within which students were asked to select the most likely cause for students to do something that might be seen as academically dishonest. The conclusions, linked research and implications for practice are relevant to anyone teaching and assessing in HE.

———————-

In 2021, UCL built on lessons learnt from the emergency pivot online in 2020 and decided to deliver all exams and assessments online. It’s led to staff from across the university engaging with digital assessment and being prompted to reflect on their assessment design in ways we haven’t seen them do before.

However, one less welcome consequence was an increase in reported cases of academic misconduct. We weren’t alone here – a paper in the International Journal for Educational Integrity looks at how file sharing sites which claim to offer ‘homework help’ were used for assessment and exam help during online and digital assessments. And its easy to see why, as teaching staff and educational developers we try to encourage group and collaborative learning, we expect students to be digitally savvy, we design open book exams with an extended window to complete them – all of which serve to make the lines around plagiarism and other forms of misconduct a little more blurry.

We worked on a number of responses: colleagues in Registry focused on making the regulations clearer and more in line with the changes brought about by the shift to digital assessment, and in the Arena Centre (UCL’s central academic development unit) we supported the development of a new online course to help students better understand academic integrity and academic misconduct.

The brief we were given was for it to be concise and unequivocal, yet supportive and solutions-focused. Students needed to be able to understand what the various forms of academic misconduct are and what the consequences of cases can be, but also be given support and guidance in how to avoid it in their own work and assessments.

Since September 2021, the course has been accessed by over 1000 registered users, with 893 students being awarded a certificate of completion. It’s too early of course to understand what – if any – impact it will have had on instances of academic misconduct. What it can already help us to think about, however, are our students’ perspectives on academic misconduct and how in turn we can better support them to avoid it in future.

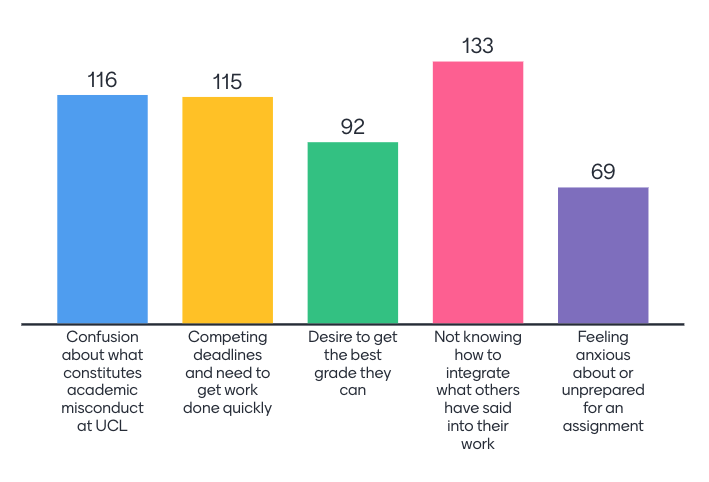

The course opens with a Menti quiz asking participants for their opinions on academic misconduct, posing the question: Why might students not always act with academic integrity? Here are the results (absolute numbers):

What they are telling us is that it is less about a lack of preparation or feelings of stress and anxiety on their part, and more a lack of understanding of how to integrate (academic) sources, how to manage their workload and what academic misconduct can even entail.

Our students’ responses are in line with research findings: studies have found a significant degree of confusion and uncertainty regarding the specific nature of plagiarism (Gullifer and Tyson, 2010) and situational and contextual factors such as weaknesses in writing, research and academic skills (Guraya and Guraya 2017) and time management skills (Ayton et al, 2021).

All of which gives us something to work on. The first is looking at how we plan our assessments over the course of a year so that students aren’t impeded by competing deadlines and unnecessary time pressures. The second is to devote more time to working with students on the development of the academic skills – and it is key that this isn’t exclusively an extra-curricular opportunity. Focusing on bringing this into the curriculum will ensure that it is accessible to all students, not just those with the times and personal resources to seek it out. Finally, as we move to more digital assessments, it is about really reflecting on the design of these to ensure they are fit for this new purpose – and perhaps the first question we should all be asking ourselves is, do we really need an exam?