Read time: 8 minutes

Introducing our new series: Top 10 Tips – a simple guide to help you achieve your goals!

In this blog post, Jessica Xie (final year UCL medical student) shares advice on getting into research as a medical student.

Disclaimers:

-

- Research is not a mandatory for career progression, nor is it required to demonstrate your interest in medicine.

- You can dip into and out of research throughout your medical career. Do not feel that you must continue to take on new projects once you have started; saying “no, thank you” to project opportunities will allow you to focus your energy and time on things in life that you are more passionate about for a more rewarding experience.

- Do not take on more work than you are capable of managing. Studying medicine is already a full-time job! It’s physically and mentally draining. Any research that you get involved with is an extracurricular interest.

I decided to write this post because, as a pre-clinical medical student, I thought that research only involved wet lab work (i.e pipetting substances into test tubes). However, upon undertaking an intercalated Bachelor of Science (iBSc) in Primary Health Care, I discovered that there are so many different types of research! And academic medicine became a whole lot more exciting…

Here are my Top 10 Tips on what to do if you’re a little unsure about what research is and how to get into it:

TIP 1: DO YOUR RESEARCH (before getting into research)

There are three questions that I think you should ask yourself:

-

- What are my research interests?

Examples include a clinical specialty, medical education, public health, global health, technology… the list is endless. Not sure? That’s okay too! The great thing about research is that it allows deeper exploration of an area of Medicine (or an entirely different field) to allow you to see if it interests you.

2. What type of research project do I want to do?

Research evaluates practice or compares alternative practices to contribute to, lend further support to or fill in a gap in the existing literature.

There are many different types of research – something that I didn’t fully grasp until my iBSc year. There is primary research, which involves data collection, and secondary research, which involves using existing data to conduct further research or draw comparisons between the data (e.g. a meta-analysis of randomised control trials). Studies are either observational (non-interventional) (e.g. case-control, cross-sectional) or interventional (e.g. randomised control trial).

An audit is a way of finding out if current practice is best practice and follows guidelines. It identifies areas of clinical practice could be improved.

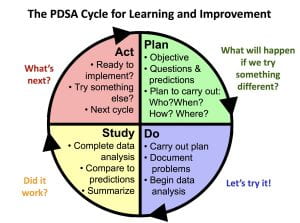

A quality improvement project (QIP) involves planning and implementing an improvement strategy, assessing if it improves outcomes or patient care and seeing how things could be further improved. QIPs follow the Plan, Do, Study, Act cycle.

Another important thing to consider is: how much time do I have? Developing the skills required to lead a project from writing the study protocol to submitting a manuscript for publication can take months or even years. Whereas, contributing to a pre-planned or existing project by collecting or analysing data is less time-consuming. I’ll explain how you can find such projects below.

3. What do I want to gain from this experience?

Do you want to gain a specific skill? Mentorship? An overview of academic publishing? Or perhaps to build a research network?

After conducting a qualitative interview study for my iBSc project, I applied for an internship because I wanted to gain quantitative research skills. I ended up leading a cross-sectional questionnaire study that combined my two research interests: medical education and nutrition. I sought mentorship from an experienced statistician, who taught me how to use SPSS statistics to analyse and present the data.

Aside from specific research skills, don’t forget that you will develop valuable transferable skills along the way, including time-management, organisation, communication and academic writing!

TIP 2: BE PROACTIVE

Clinicians and lecturers are often very happy for medical students to contribute to their research projects. After a particularly interesting lecture/ tutorial, ward round or clinic, ask the tutor or doctors if they have any projects that you could help them with!

TIP 3: NETWORKING = MAKING YOUR OWN LUCK

Sometimes the key to getting to places is not what you know, but who you know. We can learn a lot from talking to peers and senior colleagues. Attending hospital grand rounds and conferences are a great way to meet people who share common interests with you but different experiences. I once attended a conference in Manchester where I didn’t know anybody. I befriended a GP, who then gave me tips on how to improve my poster presentation. He shared with me his experience of the National institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training Pathway and motivated me to continue contributing to medical education alongside my studies.

TIP 4: UTILISE SOCIAL MEDIA

Research opportunities, talks and workshops are advertised on social media in abundance. Here are some examples:

Search “medical student research” or “medsoc research” into Facebook and lots of groups and pages will pop up, including UCL MedSoc Research and Academic Medicine (there is a Research Mentoring Scheme Mentee Scheme), NSAMR – National Student Association of Medical Research and International Opportunities for Medical Students.

Search #MedTwitter and #AcademicTwitter to keep up to date with ground-breaking research. The memes are pretty good too.

Opportunities are harder to come by on LinkedIn, since fewer medical professionals use this platform. However, you can look at peoples’ resumes as a source of inspiration. This is useful to understand the experiences that they have had in order to get to where they are today. You could always reach out to people and companies/ organisations for more information and advice.

TIP 5: JOIN A PRE-PLANNED RESEARCH PROJECT

Researchers advertise research opportunities on websites and via societies and organisations such as https://www.remarxs.com and http://acamedics.org/Default.aspx.

TIP 6: JOIN A RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE

Research collaboratives are multiprofessional groups that work towards a common research goal. These projects can result in publications and conference presentations. However, more importantly, this is a chance to establish excellent working relationships with like-minded individuals.

Watch out for opportunities posted on Student Training and Research Collaborative.

Interested in academic surgery? Consider joining StarSurg, BURST Urology, Project Cutting Edge or Academic Surgical Collaborative.

Got a thing for global health? Consider joining Polygeia.

TIP 7: THE iBSc YEAR: A STEPPING STONE INTO RESEARCH

At UCL you will complete an iBSc in third year. This is often students’ first taste of being involved in research and practicing academic writing – it was for me. The first-ever project that I was involved in was coding data for a systematic review. One of the Clinical Teaching Fellows ended the tutorial by asking if any students would be interested in helping with a research project. I didn’t really know much about research at that point and was curious to learn, so I offered to help. Although no outputs were generated from that project, I gained an understanding of how to conduct a systematic review, why the work that I was contributing to was important, and I learnt a thing or two about neonatal conditions.

TIP 8: VENTURE INTO ACADEMIC PUBLISHING

One of the best ways to get a flavour of research is to become involved in academic publishing. There are several ways in which you could do this:

Become a peer reviewer. This role involves reading manuscripts (papers) that have been submitted to journals and providing feedback and constructive criticism. Most journals will provide you with training or a guide to follow when you write your review. This will help you develop skills in critical appraisal and how to write an academic paper or poster. Here are a few journals which you can apply to:

Join a journal editorial board/ committee. This is a great opportunity to gain insight into how a medical journal is run and learn how to get published. The roles available depend on the journal, from Editor-in-Chief to finance and operations and marketing. I am currently undertaking a Social Media Fellowship at BJGP Open, and I came across the opportunity on Twitter! Here are a few examples of positions to apply for:

-

-

- Journal of the National Student Association of Medical Researchjournal.nsamr.ac.uk – various positions in journalism, education and website management

- https://nsamr.ac.uk – apply for a position on the executive committee or as a local ambassador

- Student BMJ Clegg Scholarship

- BJGP Open Fellowships

-

TIP 9: GAIN EXPERIENCE IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

UCL Be the Change is a student-led initiative that allows students to lead and contribute to bespoke QIPs. You will develop these skills further when you conduct QIPs as part of your year 6 GP placement and as a foundation year doctor.

TIP 10: CONSIDER BECOMING A STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE

You’ll gain insight into undergraduate medical education as your role will involve gathering students’ feedback on teaching, identifying areas of curriculum that could be improved and working with the faculty and other student representatives to come up with solutions.

It may not seem like there are any research opportunities up for grabs, but that’s where lateral thinking comes into play: the discussions that you have with your peers and staff could be a source of inspiration for a potential medical education research project. For example, I identified that, although we have lectures in nutrition science and public health nutrition, there was limited clinically-relevant nutrition teaching on the curriculum. I then conducted a learning needs assessment and contributed to developing the novel Nutrition in General Practice Day course in year 5.

Thanks for reaching the end of this post! I hope my Top 10 Tips are useful. Remember, research experience isn’t essential to become a great doctor, but rather an opportunity to explore a topic of interest further.

Jess