The digital objects

This case study follows the process of the digital curation and archiving of digitised photographic objects, and of the ways I attempted to implement a curation and preservation workflow using a set of tools and processes. It is, admittedly, a work in progress.

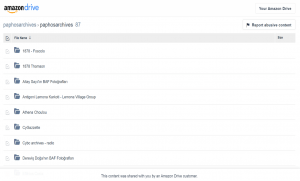

I was granted access to the material, in its current private cloud storage, by the project manager who also acted as the principal investigator and collector. The physical objects are in the custody of the legal owners. Informal licence was given to use this material in verbal terms, but no formal agreement and copyright clearance was established. Permission was given under the understanding that this was a volunteer run community operation. The volunteers aimed at digitising and disseminating the images rather than physically collecting and preserving them. However, since the majority depict identifiable people more research is necessary into copyright and data protection regulations under Cyprus and EU legal framework. Since there are multiple sources of images, I hope that the data protection issue will become clearer while the project develops and more information is gathered.

The archive of Spiros Charitou belongs to his family and beneficiaries. The beneficiary has granted access and publication authorisation for community use, however, adaptation and commercial use and reuse were not clarified, as per the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Therefore, such uses should be excluded until and if clearance is granted.

The beneficiary, himself an artist, has used, adapted and digitally manipulated part of the material in the context of an art project in 2019, suitably titled Metamorphosis. This was an interesting exercise in artistic use and reuse of archival material in its own right, even in a decomposing state, that provides food for thought when it comes to memory curation and preservation.

Overall, this was an ad hoc project without research or planning and without digital curation requirements in mind. It provided a useful exercise, as far as it replicates real life examples of messy and inordinate collections, that teaches the importance of conceptualisation, designing projects with curation and long-term preservation in mind and the importance of standards.[1]

Since I am not in possession of the actual photographs, I will treat this collection as a digital only collection of images. To begin with, the problems I face are the following:

- How to characterise these objects and make an inventory of their properties

- How to safeguard and preserve the collection from becoming obsolete

- How to use the collection and create the means for access and use/reuse

To be continued…

[1] Gillian Oliver, Digital curation / Gillian Oliver, Ross Harvey, ed. D. R. Harvey, Second edition. ed. (London : Facet Publishing, 2016), 105-11. “Lost in Translation: Understanding the Possession of Digital Things in the Cloud,” http://willodom.com/publications/paper1202-odom.pdf.