Welcome to the society’s facts page, where we hope you can engage with a broad range of topics in psychology and education. If you would like to contribute to the page, get in touch with Orianna! (o.bairaktari.16@ucl.ac.uk)

15 August 2020

Did you know? Some People with Healthy Brains Can’t Remember Their Past

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

You may have heard that some people cannot remember their life experiences due to brain damage or psychological trauma. However, Palombo et al. (2015) found that some people with healthy brains can have severe difficulties with their autographical memory.

Palombo et al. (2015) studied three individuals: AA, a married woman aged 52, BB, a single man aged 40, and CC, aged 49 and living with their partner. All of them were high-functioning in their daily lives with intact memory of facts and skills. However, they expressed for all their lives, they couldn’t recollect any of their past events from the first-person perspective.

To test their memory, the researchers interviewed AA, BB and CC about different past incidents. Their responses were then compared to 15 participants who were similar in age and educational background. The results showed that AA, BB and CC provided significantly fewer autobiographical details from when they were adolescents and young adults. Furthermore, they could only describe their past from a third-person perspective (e.g. he, she, they). It was also difficult for them to imagine future events. Their memory of recent events was deemed relatively normal, but the researchers think this might be due to the participants’ having learnt compensation strategies, such as reviewing their diaries and photos.

To identify the underlying reasons for their lack of autobiographical memories, the researchers tested their intelligence, memory and mental performance. All three individuals performed above average on all the tasks except for one: they could hardly draw a complex picture from memory.

In addition to the tasks, all three individuals had their brains scanned, and no brain damage or illness was found. However, the brain areas associated with autobiographical memory (i.e., parts of temporal lobes, medial prefrontal cortex and the precuneus) showed less activity when the three individuals tried to recall their past experiences. Their right-sided hippocampus was also found to be slightly smaller than those of the comparison participants. Palombo et al. (2015) therefore suggested that their difficulties with autobiographical memory stemmed from a deficit in their visual memory as well as reduced activation in these brain regions.

However, a key limitation of the study was the small sample size. With only three target participants, it is not possible to generalize the findings to the wider population. As of now, there is no neurological or psychiatric evidence to explain Palombo et al.’s (2015) findings. Therefore, more individuals with this peculiar syndrome are needed in order for this phenomenon to be explored further.

References

10 August 2020

Did you know? Over-confidence Could Be Spread Between Group-Members

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

It is not uncommon to find that some social groups are more confident than others. For example, individuals who grew up in individualistic cultures (e.g. the United States) tend to show higher levels of confidence compared to individuals who grew up in collectivist cultures (e.g. Japan, China). Between culture comparisons aside, research has sought to explain why people within the same groups often show similar levels of confidence.

Cheng et al. (2020) found that a bias towards over-confidence can be spread from person to person within a group. They suggest we calibrate our self-assessment based on the confidence levels of the people around us. In summary, if we are exposed to people who are over-confident, this can rub off on us.

Cheng et al. (2020) conducted six studies to explore this phenomenon. In the first study, 104 university students were asked to individually complete a task in which they had to guess the personality traits of 10 people from photographs. They then had to rank themselves according to how well they thought they’d done compared to the other participants. Then, they were randomly paired with a confederate to complete the task and rank their own performance again.

The results revealed that working with someone who had thought more highly of their performance made the participant rank their performance higher (i.e. the participant became more confident about their own performance after the joint task). The subsequent five studies found that people were often unaware of this transmission of over-confidence. However, this transmission only occurred within in-groups: participants were only affected by people who identified themselves as coming from the same university but not those who were identified as coming from a rival university.

This study can potentially explain why people within the same group tend to have similar levels of confidence. Also, the fact that biased beliefs (i.e., over-confident beliefs) can be widespread within a group can inform group leaders to pay more attention to individuals who may be over-confident and can potentially disrupt the unity of the group.

However, a primary limitation of this study is that it solely focused on over-placement as one form of over-confidence. Whether other forms of over-confidence, such as over-estimation and over-precision, can be transmitted from person to person is yet to be determined. Therefore, future research should take more forms of over-confidence into account.

References

8 August 2020

Did you know? Movies Like Joker Can Perpetuate Prejudice Towards People with Mental Illness

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

The stigmatisation of mental illness has been an enduring, significant social issue. An issue that may be perpetrated by the ‘madman’ caricature and the disturbing depictions of asylums frequently appearing in films, literature and TV series. Research has sought to understand how the media influences attitudes towards individuals struggling with mental illness. A recent study by Scarf et al. (2020) investigated the impact of the critically-acclaimed DC comics’ Joker on prejudice towards individuals struggling with their mental health.

The film features Arthur, the male protagonist whose behaviours and actions throughout the film suggest he is struggling with some form of serious mental illness. Due to budget cuts, he stops receiving medication and subsequently goes on a violent rampage. Arthur’s character consequently depicts people struggling with mental illness as violent and brutal.

Scarf and colleagues asked 84 participants to attend a screening of Joker and 80 participants to attend a screening of Terminator: Dark Fate (a film with no depiction of mental illness). All participants then completed the Prejudice Toward People With Mental Illness (PPMI) scale (Kenny, Bizumic & Griffiths, 2018). before and after the screenings. Questions included to what extent do the participants fear or avoid people with mental illness, and whether they view people with mental illness as malevolent.

Results indicated that the mean PPMI score after watching Joker (M=3.20, SD=0.78) was significantly higher than before watching the movie (M=2.99, SD=0.66), which suggests the movie strengthened negative perceptions of mental illness. In contrast, participants who watched Terminator: Dark Fate had similar scores before and after watching the movie (M= 2.91 and M= 2.88 respectively).

A major limitation of the study is that it did not assess whether viewing Joker was associated with actual discriminatory behaviours. Although there are questions asking about respondents’ discriminatory behaviours in the PPMI scale, self-reported data tends to be weak in validity due to demand characteristics such as social desirability bias (i.e. answering questions on the scale in a manner that will be viewed more favourably by others).

Media undoubtedly has a significant impact on our attitudes and beliefs about the world and the people we encounter. Therefore, further research into the impact of the entertainment industry on attitude formation may be useful in informing said industry to remember that people struggling with mental illness are still people, and should be depicted as such.

References

3 August 2020

Did you know? We can identify the degree of familiarity between people solely by hearing their laughter

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

The sound quality and frequency of laughter has been observed to differ between genders and is also affected by the composition of social groups. For example, friends are more likely to laugh together compared to strangers, and female friends laugh together more than male friends. The patterns of laughter can provide us with rich information about the social relationships within groups. However, can listeners outside of a group effectively use this information to identify the strength of the social bonds within that group?

Bryant et al. (2016) conducted an experiment to examine whether listeners can determine the degree of familiarity and social closeness between pairs of people solely based on brief decontextualised recordings of co-laughter. They found that people across cultures could reliably distinguish friends from strangers by hearing laughter.

The researchers asked pairs of American English-speaking undergraduate students to talk about various topics (e.g. bad roommate experiences) in a laboratory. Some students were paired with their good friends and some students were paired with students they didn’t know. Their conversations and laughter were recorded. From these recordings, researchers extracted instances of ‘co-laughter’ (times when the paired students laughed at the same time).

966 participants from 24 cultural backgrounds were asked to listen these laughter clips and identify the relationship between the people on the recording (friends or strangers). The results revealed that the participants could distinguish friends from strangers with an accuracy rate of 53-67%. The results indicated that people laugh differently with friends than they laugh with strangers. Between friends, each burst of laughter lasted shorter, and these bursts were more irregular in pitch and volume. Moreover, Bryant et al. (2016) found that the listeners’ ability to judge affiliation based on decontextualised instances of co-laughter was consistent across cultures. Even listeners who were not familiar with the English language were found to make reliable and accurate judgements.

Bryant et al. (2016) suggested this ability may be evolutionary in origin: by being able to recognise the social relationship between individuals from a distance, people could know whether a particular group is united and worthwhile to join in or if the group might be potentially threatened by a stranger. However, there is little empirical evidence demonstrating the evolutionary roots of such an ability. It has been suggested that future neurological and/or animal studies can explore the underlying mechanism of this ability in further depth.

References

31 July 2020

Did you know? When presented with angry and fearful faces, there are differences in brain activity between bullies and victims of bullying

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

Relational victimisation and bullying are common social experiences during adolescence. Both experiences could seriously affect our mental health and well-being. Research has sought to understand the predictors of bullying and victimisation in order to reduce these experiences.

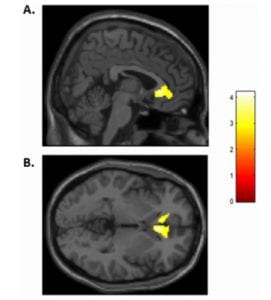

Swartz, Carranza and Knodt (2019) conducted a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study to examine the association between brain activity during an emotional face-matching task and self-reported peer relational bullying and victimisation. The study revealed that the victims and bullies had different brain responses to angry and fearful faces.

49 adolescents aged 12 to 15 years-old were recruited as participants. They were asked to complete a self-report survey measuring their experiences of relational bullying and victimisation over the past 12 months (‘Never’ to ‘A few times a week’). Then, participants completed an emotional face-matching task including images of faces that were angry, happy and fearful whilst being scanned.

The results indicated that the participants who showed stronger activity in the amygdala to angry faces and weaker activity in the amygdala to fearful faces reported higher scores of bullying. Meanwhile, participants who showed stronger activity in the amygdala to angry faces and fearful faces reported higher levels of peer victimisation. Swartz et al. (2019) further found that stronger activity in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) to fearful faces was associated with less bullying behaviours.

Although the exact reasons as to why bullies and victims show different patterns of brain activity to emotional faces is not yet clear, Swartz et al. (2019) give some possible explanations. The amygdala is an almond-shaped brain structure involved with the experiencing of emotions. Adolescents who show stronger activity in the amygdala activity when presented with angry faces may easily misinterpret peers in ambiguous situations as being intentionally hostile, which can lead to more conflict. Meanwhile, their weaker response to fearful faces may be related to decreased ability to perceive others’ distress and thus less likely to feel empathetic. This combination can lead to an increased display of bullying behaviours.

The rACC is a brain region involved in the integration of social and emotional information. Therefore, participants who showed stronger activity in the rACC when presented with fearful faces may be more likely to feel others’ distress, which may reduce their bullying behaviours.

However, it is important to emphasise that a cause-effect relationship cannot be established from this study. It can be suggested that the differences in strength of activation in the amygdala may not be predictors of bullying and victimisation, but rather, the product of being bullied or having engaged in bullying behaviour. In addition, the sample size of the study was relatively small, weakening the finding’s generalisability to the wider population.

Further research is needed to investigate the psychological mediators (e.g. levels of empathy) of these effects.

‘If these effects are replicated and extended to longitudinal research in the future, they will help to elucidate how biased patterns of social and emotional processing may increase risk for bullying and victimisation in adolescents and could lead to more tailored intervention approaches’.

References

28 July 2020

Did you know? Growing up with grandparents can impact children’s perceptions of older adults

Yan Yan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

Research from the United States has demonstrated that there is an increasing number of grandparents who are living with their grandchildren. Consequently, the contact between grandparents and young children has become more frequent (Glaser, Stuchbury, Price, Di Gessa, Ribe & Tinker, 2018). Research has investigated the impact from this increase in prolonged contact between children and their grandparents.

Social psychologists Smith and Charlton (2020) investigated the impact of growing up in a household with an older adult on young children’s attitudes toward the elderly. They found that this shift in household composition lead to negative outcomes: those who grew up with grandparents had significantly lower opinions of the elderly.

In their study, 309 participants were recruited, 194 of which grew up with a grandparent. Participants completed a set of surveys exploring their general attitudes towards the elderly, contact frequency, interaction positivity, current anxiety towards interaction with the elderly, and anxiety levels about growing old themselves.

The results indicated that the participants who grew up with a grandparent had significantly more negative opinions toward older adults, especially when their grandparents were ill. This particular finding can be explained by the nature of caring for an older adult. Studies have shown that being a caregiver can negatively impact one’s physical and mental health (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). However, participants had less anxiety about their own ageing process, which might be due to that the younger adults experience cognitive dissonance. Younger adults may feel panic by frequently being in contact with the elderly. In order to decrease this discomfort, they may tell themselves that their ageing outcomes will be different.

A major limitation of this study is that all participants were American, so the results have weak cross-cultural validity. Nonetheless, this study illustrates that purely increasing the contact frequency between grandparents and young children can potentially negatively impact young people’s attitudes towards the elderly. Smith and Charlton (2020) therefore suggest that in order to establish a more positive relationship, focusing more on the quality of the contact, instead of the frequency, can promote the formation of positive attitudes between children and their elderly relatives.

References

26 July 2020

Did you know? You shouldn’t prepare for your exams by re-studying your notes

Yanyan Zong (Year 2 BSc Psychology with Education)

Proofread by Kyleigh Melville (BSc Psychology with Education Alumnus)

Re-reading lecture slides and trying to memorise our notes are two common ways we use when we prepare for exams. However, recent psychological research has found that there are much more effective strategies of studying.

Ebersbach, Feierabend and Nazari (2020) conducted an experiment and found that the learners who answered practice questions or generated questions about the learning materials during revision performed better than those who only re-studied their notes in the later exams.

In their experiment, 82 German university students in a developmental psychology lecture were randomly assigned into one of three groups. All three groups received 10-pages worth of material on the development of knowledge in infants. In the ‘Re-study’ group, students were told that they only needed to memorise what was on the pages. In the ‘Testing’ group, students were given one question from each page to answer. The students in the ‘Generating’ group were to generate test questions related to the content themselves. After one week, all the students received a surprise exam, testing their understandings of the content they have learned. The exam included five factual questions, which were directly related to the content they were given, and five questions which tested their ability to apply what they have learned to different contexts.

The results showed that participants in the ‘Re-study’ group scored about 45% on the exam. In contrast, participants in the ‘Testing’ and ‘Generating’ group scored on average 11% higher. This suggests that both generating questions and testing are significantly better strategies than simply re-studying one’s notes. In addition, participants in the ‘Generating’ and ‘Testing’ group performed better on answering both factual and transfer questions, indicating that these two strategies facilitated not only factual learning, but also the ability to apply knowledge to unfamiliar situations.

This concept is known as desirable difficulties, in which mechanisms make the learning process subjectively harder and more effortful but in doing so, assist students to retain knowledge longer (Bjork, 1994). During the knowledge acquisition phase, being tested and generating questions helps students to process information deeper than passively receiving knowledge, so they could recall information better in later exams.

One obvious limitation of this study is the small sample size —— each condition had less than 30 participants. Therefore, it is essential to replicate the experiment with a larger sample size in order to enhance the generalisability of the findings. In addition, the fact that all participants were college students made the findings harder to generalised to younger learners. It may be that these strategies are not as effective when the participants are primary school students, who may face difficulties in generating questions themselves.

Nevertheless, this study has clear implications for university students who want to find better strategies to prepare for upcoming exams. Teachers could also make use of these two strategies in their lectures to facilitate their students’ learning and revision.

References

2 July 2020

Did you know that the largest school in the world is in Lucknow, India? The City Montessori School has more than 55,000 students. It is a private school where students are taught English. The school currently consists of 18 campuses around the city and since 2013 is an official centre for SAT exams. The school that initially had just five pupils has certainly grown. Take a look at their official site.

4 June 2020

This one is for the Dr Who fans! Did you know that the UCL Knowledge Lab has a project named TARDIS? Although instead of Time and Relative Dimension in Space, in this case TARDIS stands for raining young Adult’s Regulation of emotions and Development of social Interaction Skills. Click here to read more about the project. Allons-y!

Happy Mental Health Awareness week! While we still have a long way to go regarding mental health and education, since 2020 there are three US states that have approved mandatory mental health curriculum; New York, Virginia and Florida. 47 more to go!