For many years we have predicted that the future provision of universities will be ‘blended’, where a share of onsite learning will be replaced by online activity. During the pandemic, many teachers and students experienced a version of the blend. Due to the lack of time, that blend tended to be framed more by technological possibility than pedagogical potential, but it at least took us beyond the ‘getting started’ phase. One of the publications listed in the 2022 Horizon Report, Planning for a Blended Future: A Research-Driven Guide for Educators, argues that, “now is the time to think strategically and calculate our next steps in reconceptualizing blended learning within our courses and programs to ensure quality by carefully considering the dialectical of technology, time, space, and pedagogy, while integrating modalities in order to build the future, the blended university”.

For many years we have predicted that the future provision of universities will be ‘blended’, where a share of onsite learning will be replaced by online activity. During the pandemic, many teachers and students experienced a version of the blend. Due to the lack of time, that blend tended to be framed more by technological possibility than pedagogical potential, but it at least took us beyond the ‘getting started’ phase. One of the publications listed in the 2022 Horizon Report, Planning for a Blended Future: A Research-Driven Guide for Educators, argues that, “now is the time to think strategically and calculate our next steps in reconceptualizing blended learning within our courses and programs to ensure quality by carefully considering the dialectical of technology, time, space, and pedagogy, while integrating modalities in order to build the future, the blended university”.

Before 2020, many institutions were experimenting with forms of blended learning, but online activity was often seen as an extra, added to the existing course structure, the so-called ‘course-and-a-half’ approach. During the pandemic, expedient technical fixes often lacked even this basic type of design and integration, and we know student engagement suffered. Now the emergency has passed, “it is now time to rethink the mixing and matching of technology solutions to thoughtfully designed and well-integrated courses and programs that can capture the essence of the blend through engaged learning that positively influences student outcomes”.

Rethink your course’s learning objectives in a strategic way to maximize the opportunities of the learning environment. Determine which objectives can be accomplished considering a student’s location (onsite or online) and time (live and in real-time or at a student’s own pace over time).

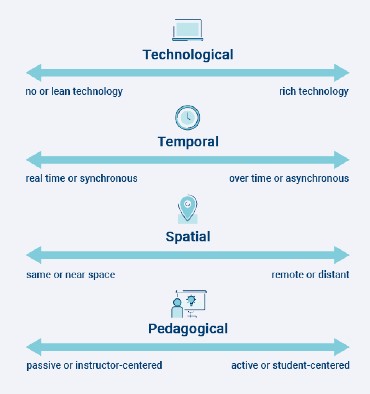

Recognising the fuzziness of terminology in this area, the paper uses a four-part model of blended learning (see right).This model can apply to whole programmes as well as modules/courses

A design strategy is most effective when it facilitates an integration that includes consideration for both onsite and online as well as live or synchronous and asynchronous along with the type of activities that are student-centered and active

The paper gives an example where the onsite classroom is kept for richer learning tasks that require “more communication cues and interactions”, such as higher order practical activities and peer-work that “require a quick back and forth exchange” while the online is used for didactic material, quizzes and asynchronous discussion. The importance point is that these need to be fully integrated and the student journey carefully scaffolded. The paper’s emphasis on scaffolding is especially interesting.

Each step provides the learner with details as to what they are supposed to do, how, where, and with who, as well as how it will be assessed, providing for frequent feedback on their learning. Scaffolding helps learners stay engaged which is often more difficult when working remotely while moving sequentially towards the learning objectives of the course.

It makes the point that scaffolding “can be embedded in learning environments, interaction, the structure of activities, artifacts, and technologies”.

The paper includes a useful checklist, Ten Questions for Blended Course Redesign, originally from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.