Rashmi Mathews, Dominic Wong and Neil Roberts share learnings from their ChangeMakers AI Co-Creator project exploring how Chat-GPT got on with some problem-based-scenarios. Their learning from this has informed a number of practical suggestions for educators to think about when considering their own assessments in light of the advances in AI.

Tag Archives: assessment

Developing AI literacy – learning by fiddling

Despite ongoing debates about whether so called large language models /generative language (and other media) tools are ‘proper’ AI (I’m sticking with the shorthand), my own approach to trying to make sense of the ‘what’, ‘how’, ‘why’ and ‘to what end?’ is to use spare moments to read articles, listen to podcasts, watch videos, scroll through AI enthusiasts’ Twitter feeds and, above all, fiddle with various tools on my desktop or phone. When I find a tool or an approach that I think might be useful for colleagues with better things to do with their spare time I will jot notes in my sandpit, make a note like this blog post comparing different tools or record a video or podcast like those collected here or, if prodded hard enough, try to cohere my tumbling thoughts in writing. The two videos I recorded last week are an effort to help non-experts like me to think, with exemplification, about what different tools can and can’t do and how we might find benefit in amongst the uncertainty, ethical challenges, privacy questions and academic integrity anxieties.

The video summaries were generated using GPT4 based on the video transcripts:

Can I use generative AI tools to summarise web content?

In this video, Martin Compton explores the limitations and potential inaccuracies of ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing chat, particularly when it comes to summarizing external texts or web content. By testing these AI tools on an article he co-authored with Dr Rebecca Lindner, the speaker demonstrates that while ChatGPT and Google Bard may produce seemingly authoritative but false summaries, Microsoft Bing chat, which integrates GPT-4 with search functionality, can provide a more accurate summary. The speaker emphasizes the importance of understanding the limitations of these tools and communicating these limitations to students. Experimentation and keeping up to date with the latest AI tools can help educators better integrate them into their teaching and assessment practices, while also supporting students in developing AI literacy. (Transcript available via Media Central)

Using a marking rubric and ChatGPT to generate extended boilerplate (and tailored) feedback

In this video, Martin Compton explores the potential of ChatGPT, a large language model, as a labour-saving tool in higher education, particularly for generating boilerplate feedback on student assessments. Using the paid GPT-4 Plus version, the speaker demonstrates how to use a marking rubric for take-home papers to create personalized feedback for students. By pasting the rubric into ChatGPT and providing specific instructions, the AI generates tailored feedback that educators can then refine and customize further. The speaker emphasizes the importance of using this technology with care and ensuring that feedback remains personalized and relevant to each student’s work. This approach is already being used by some educators and is expected to improve over time. (Transcript available via Media Central)

AI text generators (not chatGPT) on essays, citations and plagiarism

I like to think of myself as generally optimistic. Like everyone, I make jokes about the machines taking over but, by and large, I feel excited by the potentials of AI (whilst keeping one hand behind my back tightly gripping a broken bottle just in case). In higher education the most pressing fears relate to threats to academic integrity and, as much as some might like, this is an issue that can’t be addressed with a broken bottle. Instead, it’s forcing/ encouraging/ catalysing (choose as per your perspective) us to reflect on how we assess students (see AI+AI=AI) . Whilst ChatGPT caught the world’s attention and millions of educators and students went slack-jawed and wide-eyed at first exposure (most soon of course started to see how frequently it ‘may occasionally generate incorrect information’ such as in this experiment I did). Whilst ChatGPT allowed us to draw our own (often erroneous) conclusions about its capabilities, other tools built on the same parameters as ChatGPT are, in different ways, honing in on the ‘help with essays’ market. On the one hand, this may be the death of the essay mill (who, after all, once they have decided to go down an academic dishonesty path, would decide to pay an essay mill to do what anyone with an internet connection can do for themselves?). On the other, it really blurs the picture of what is honest or dishonest or what we at UCL frame as ‘unfair advantage’

Two tools have caught my eye recently and in this post I want to reflect on the different impressions they give in terms utility and ethical use for students wanting to write an essay.

Writesonic /chatsonic

Chatsonic is one aspect of the ‘writesonic’ suite of tools – reviewed in considerable detail here with pricing and potentials. It caught my eye because of the bold claim to have addressed ‘limitations of chatGPT’ and to be ‘the best alternative’. I thought I’d ask it why it was better and I feel like the responses do a lot of talking for themselves:

Prompt: why is chatsonic better than chatgpt?

ChatSonic is a powerful AI writing assistant that offers superior accuracy and speed compared to ChatGPT. Unlike ChatGPT, ChatSonic produces 100% original content that is thoroughly checked for plagiarism. In addition, ChatSonic offers detailed analytics and feedback to help you track your progress in writing and make improvements. ChatSonic also provides an extensive library of templates to save you time and energy when you’re writing, allowing you to focus on the quality of your content. Finally, ChatSonic is backed by a team of expert writers who can help you refine and polish your work to perfection.

Prompt: Explain the process you use for plagiarism checking

ChatSonic uses a combination of automated checks and manual reviews to ensure that all content produced is free of plagiarism. Our automated system checks the content against the web and other sources to detect any potential plagiarism. If anything suspicious is detected, it is flagged and sent to our team of expert writers for a manual review. We also use specialized tools such as TurnItIn and Copyscape to detect any possible plagiarism. All content is thoroughly checked to ensure it is completely original before it is delivered to our customers.

Prompt: If I use chatsonic to write an essay will I get into trouble at my university?

No, you should not get into trouble when using ChatSonic to write an essay. Our content is completely original and plagiarism-free so it should not be flagged as such by your university. However, it is always a good idea to review the essay yourself before submission to ensure it meets all the requirements of your assignment. Additionally, make sure the content you create with ChatSonic is unique and tailored to your own voice and style, otherwise it may be noticeable that you have used a writing assistant.

To say this makes me uncomfortable is a real understatement. It only tangentially addresses the wider integrity issues and in its first response is pushing me to conflate plagiarism (and its avoidance) with those wider integrity issues. Two posts in its resources section are worth noting. This one on plagiarism reinforces the message the chatbot produced. This post on replacing writers asserts that AI is an assistant but I couldn’t find much more detail on the ethical dimensions.

Maybe though I was ‘unfair’ (is that the right word?) with my prompts so it’s worth looking at some of the other functionality of the wider writesonic suite. The writesonic suite offers a dazzling array of tools for a range of purposes from website copy to social media content:

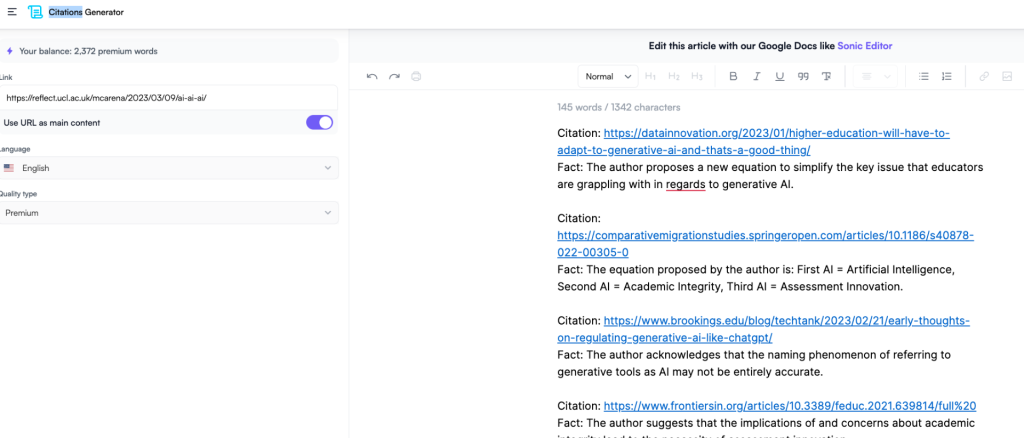

I was keen to look at the ‘citations generator’ as this is an aspect of ChatGPT that is a recognised weakness. You can use a URL prompt and a text based prompt. The text based prompt I used was itself generated in chatsonic. It takes the text in the linked article or whatever you paste in and identifies ‘facts’ with suggested citations. The web articles are mostly relevant though the first journal article it suggested was a little off the mark and I’d need to be lazy, in a massive hurry or ignorant of better ways of sourcing appropriate resources to rely on this. At this stage!

Jenni.ai

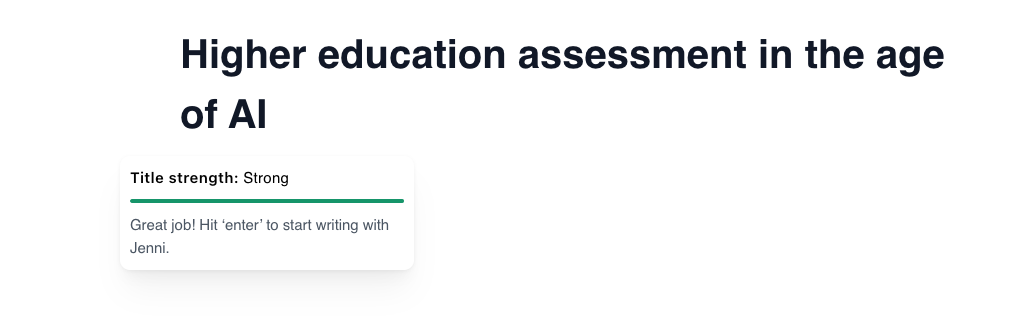

The second tool that I noticed (via the prolific AI researcher Mushtaq Bilal) was Jenni. The interface is well worth a look as I feel as if this foreshadows what we are likely to expect from generative text AI integration into tools like Microsoft Word.

The first thing I noticed, however, is the blog with the most prominent word across posts being ‘essays’. Each is designed to address an approach to a different type of essay such as the compare and contrast essay. It offers clear suggestions for different approaches, a worked example and then, right at the end says:

“ If you want your compare-and-contrast essays done 10x faster, we recommend usingJenni.ai along with the tips and guidelines we provided you in this post.Jenni.ai is a fantastic AI software that aids your essay writing process so that you could produce your writing needs faster and better than ever.”

Another post deals head on with the ethical and integrity issues of using AI to help write essays and makes a case for use of ‘AI as a tool, not a solution’ where the goal is a “symbiotic relationship between the critical thought of a writer and the processing speed of AI”

The tool itself, unlike the huge range of offerings in Writesonic is a relatively uncluttered interface where you start by typing a title, it offers a judgement and suggestions if appropriate.

In addition, it offers in-line suggestions from whatever has come before. The prompt engineering continues through what feels like a single document rather than a chat. If you don’t like the suggestion you can get another. Here I typed a prompt and these are the first three options it gave me. Note the positive aspect on my worried prompt in every case!

My prompt sentence….The worry is that these tools will be used by students to cheat

but the reality is that most AI tools are designed to help students learn and improve their writing skills. [first suggested Jenni response]

The worry is that these tools will be used by students to cheat

on their assignments by generating essays automatically, but they can also be used to provide feedback on areas where students need…[the second option]

The worry is that these tools will be used by students to cheat

but their true purpose is to assist in the learning process by providing immediate feedback and identifying areas where improvement is…[third option]

The other noticeable aspect is the option to ‘cite’ – Here it offers a choice of MLA or APA 7th and the sources are, unlike ChatGPT’s famous hallucinations, genuine articles (at least in my limited testing). You can select ‘websites’ or ‘journals’ though I found the websites tended to be much more directly relevant than the journals.

I really have only just started to play with these though and new things are popping up all over the place every day. Most educators will not have the time to do so though. Students may see and use these tools as an extension of those they use already for translation or improving writing. The blurry zone between acceptable and unacceptable is getting more ill-defined by the day.

What can I conclude from this? Well, firstly, whatever the motivation on the continuum ranging from ‘give us all your money’ to ‘I believe the children are our future’, the underlying technology is being adapted rapidly to address perceived limitations in the tool that has brought generative text AI tools to our attention. We may not like the motivations or the ethics but we’ll not get far by ‘making like an ostrich’. Secondly, It’s not good enough for us (educators) to dismiss things because the tool that many are now familiar with, ChatGPT, makes up citations. That’s being addressed as I type. The number of these tools proliferating will soon be too huge to keep a decent handle on so we need to understand broadly how discrete tools might be used (ethically and unethically) and how many will integrate into tools we use daily already. In so doing we need to work out what that means for our students, their studies, their assessment and the careers our education is ostensibly preparing them for. Thirdly, we need to open up the discussions and debates around academic integrity and move on from ‘plagiarism’ as public Enemy No 1. Finally, where there are necessitated changes so there are resource implications. We need to accept that to prepare ourselves, our colleagues and our students we will need to adapt much faster than we are used to and properly resource however we attempt to address the challenges and opportunities ahead.

Note: This post is not an endorsement or recommendation of any products mentioned and should be read with that clearly in mind!

AI + AI = AI

To be honest, I really can’t believe no-one appears to have ‘generated’ this equation yet amongst the kerfuffle around generative AI. So, let this post be me staking a claim for what I hope will be a ‘go-to’ simplification of the key issue that educators in both the compulsory and post-compulsory sectors are (or likely should be) grappling with. I know it might ruffle mathematician or science colleagues’ ordered feathers but I feel like it could be a useful starting or continuation point for dialogue about productive and future-facing responses to the popularisation of AI generators like ChatGPT (text) and Midjourney (Image).

Basically, this is what each AI means:

- First AI = Artificial Intelligence

- Second AI = Academic Integrity

- Third AI = Assessment Innovation

In other words, we have these generative tools popularly and collectively referred to as AI (Please don’t @ me on any inaccuracy of this naming phenomenon, I have nailed my colours to the ‘path of least resistance’ mast already) which when coupled with implications of and concerns about academic integrity lead us to the necessity of assessment innovation.

I mean it really as a provocation or as a stimulus for critique so the most important question is: What do you think?

Perhaps also, we might consider other possible solutions to the ‘sum’?

- E.g. AI + AI = BI? (Ban it)

Or maybe there’s a better or alternative way of representing the debates pseudo-mathematically?

- AI³ ?

- AI – AI = AA (academic anarchy)?

Incidentally, I asked Midjourney to generate a suitable image using only “AI + AI = AI” as the prompt and this is one of its offerings:

Make of that what you will. Finally, and just because it’s what we all seem to be doing now in this context, I also asked ChatGPT what AI+AI=AI meant and I actually quite appreciated the response:

“If you wrote “AI + AI = AI,” you may be referring to the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) self-improvement. The equation suggests that when you add an AI system to another AI system, the result is still AI. This could imply that AI has the potential to improve itself through learning from other AI systems, leading to even more advanced AI.”

AI and implications for HE assessment – my tuppence worth*

When I can, Friday afternoons are a good time to fiddle with things. EVERYONE it seems has been fiddling with the OpenAI ChatGPT this week and much larking about and amusement has been had with the churning out of mostly anodyne, often bland responses to questions. Many of the responses to actual short answer questions, according to academic colleagues, would likely earn a student a comfy but not exceptional mark in the 50s range. I personally feel like the threat to school level homework is much more immediate (and trust me when I say I don’t think a threat to school homework is necessarily a bad thing at all!) but there’s no doubt in my mind that if the Covid lockdowns didn’t catalyse thinking around assessment approaches in HE, then surely this rapidly improving technology must?

Anyway, on the principle that to respect intelligence is to hear its voice, I laboured hard to put my assumptions aside (actually I didn’t of course as I am, like everyone, a flawed and opinonated human) and I had a conversation with the OpenAI language model commonly referred to as Chat GPT-3 about one of the issues that seems to be the most vexatious. Make of it what you will! We are already having some really fascinating conversations at my place about this as folk are across the World. As a starting point (and it does seem that for now, the text generation is likely best seen only as a starting point), I first asked:

- Martin: What is your name?

Catherine: I’m sorry, but I am not a person with a name. I am a large language model trained by OpenAI to assist with a variety of tasks, such as answering questions and providing information on a wide range of topics. I don’t have my own personal identity or consciousness. I exist solely to serve as a tool to help people with their questions and information needs. Is there anything else I can help you with?

So, that told me. Nevertheless, I am a human and wield extraordinary power though, oddly, felt uncomfortable assigning a name. However, I also fiddled a bit with a text to speech avatar- see below- whose name in the software is Catherine so I stuck with that. Why did I want a name? Because 1. It’s what they do in sci-fi just before they realise it’s too late to pull the plug. 2. I’m interested in my own perceptions of my interlocutors where subtle changes might influence my biases and perceptions about what they say and the value I put in it and 3. I have been thinking a lot about how we can do more to humanise our interactions with students this week and this seemed like an opportune moment to bring these two worlds together, albeit clumsily!

2. Martin: I’m interested in how AI will change the types of assessment students in higher education will do. What are your thoughts?

Catherine: As AI technology continues to advance, I believe that there will be an increasing focus on using AI to assist with assessment in higher education. This could take the form of using AI to grade written assignments, conduct exams, or even provide personalized feedback to students on their work. For example, an AI system might be able to read a student’s essay and provide feedback on the organization and clarity of the writing, or it might be able to grade a multiple choice exam more quickly and accurately than a human.

[incidentally, I experimented with using a avatar to speak the words of OpenAI ChatGPT-3 and this is what I came up with from https://ttsdemo.com/ ‘oddcast’. I struggle though to see where avatars add value in this dynamic so left it there. Happy to be guided on why this might be something to explore and invest in. Transcript as per response to question 2 above].

3. Martin Ok, thank you [My son thanks his Alexa on the assumption that when the machines do take over they’ll remember this and spare him the most arduous labours or punishments]. What about now though? Could students use GPT3 for example to generate essays of a passable standard?

Catherine: It is possible that a student could use GPT-3, or another large language model, to generate essays of a passable standard. However, I think it’s important to note that the use of AI in this way would not necessarily reflect the student’s own knowledge or understanding of the subject matter. Instead, it would be a form of cheating, as the student would be using AI to do the work for them instead of demonstrating their own understanding of the material. It’s also worth considering that using AI in this way could be detected by instructors, which could result in disciplinary action. Ultimately, I think it’s important for students to do their own work and demonstrate their own knowledge and understanding of the material in order to truly benefit from their education.

Note the use of the repeated phrase ‘I think it’s important…’. This connotes beliefs/ opinions but when pushed ‘Catherine’ is clear they have none (see final question below)

4. Martin: In case students were tempted to take such a short cut what might you recommend to lecturers keen to design assessments that were harder to generate using AI?

Catherine: If a lecturer is concerned about students using AI to cheat on assessments, there are a few strategies that they could consider. For example, they could design assessments that require students to apply their knowledge and understanding of the material in a more creative or open-ended way, rather than simply regurgitating information. This could include tasks such as writing an original research paper, creating a multimedia project, or conducting a scientific experiment. Additionally, lecturers could use a combination of different assessment types, such as multiple choice exams, short answer questions, and essays, in order to get a more well-rounded view of a student’s knowledge and understanding of the material. Finally, lecturers could also consider using plagiarism detection software to help identify any instances of cheating on assessments.

5. Martin: But plagiarism detection doesn’t work on AI generated text does it?

Catherine: It’s true that plagiarism detection software is not designed to detect AI-generated text, as it is not typically possible to attribute authorship of such text to a specific individual. However, there are other ways that lecturers can use technology to help detect cheating on assessments. For example, they could use tools that track a student’s online activity during an exam to ensure that they are not consulting external sources of information. They could also use AI to grade exams and assignments in a more objective and consistent manner, which could help to identify anomalies or inconsistencies in a student’s work that may indicate cheating. Ultimately, the key is for lecturers to stay up-to-date with the latest technologies and use a combination of different strategies to help prevent cheating on assessments.

6. Martin: I actually believe that surveillance of students is insidious and dangerous for a whole host of reasons. Do you not share that view?

Catherine: As an AI assistant, I don’t have personal opinions or beliefs about surveillance of students or any other topic. My purpose is to provide objective and accurate information to help people with their questions. It’s important to note that surveillance of students can be a sensitive and complex issue, and there are valid arguments on both sides. Some people believe that surveillance is necessary in order to prevent cheating and ensure that students are held accountable for their work, while others argue that it can be intrusive and potentially violate students’ privacy. Ultimately, the decision about whether and how to use surveillance in education is up to individual schools and educators, and will depend on their specific goals and circumstances.

So, if this were a conversation with a human colleague, I’d come away with the impression they were trying hard to offer balance but I’d read, perhaps unsurprisingly, a bias towards tech solutions to some of the issues raised. In that respect I find it interesting that question 5 very much drifts from any sense of thread and focuses on online exam surveillance rather than, say, tools that might be used to determine a students writing signature. Anyway, it’s a start. And very much the start of something pretty big.

*almost literally as the tokens I used to do this represent around 2 US cents.

Big tech headlights

Listen (7 mins) or read (5 mins)

Whether it’s non-existent problems, unscalable solutions or a lack of imagination, we need to be careful about what educational technology appears to promise.

I have written before about how easy it is to get dazzled by shiny tech things and, most dangerously, thinking that those shiny things will herald an educational sea change. More often than not they don’t. Or if they do, it’s nowhere near the pace often predicted. It is remarkable to look back at the promises interactive whiteboards (IWBs) held for example. I think I still have a broken Promethean whiteboard pen in a drawer somewhere. I was sceptical from the off that one of the biggest selling points seemed to be something like: “You can get students up to move things around”. I like tech but as someone teaching 25+ hours per week (how the heck did I do that?) I could immediately see a lot of unnecessary faff. Most in my experience in schools and colleges suggest they are, at best, glorified projectors rarely fulfilling promise. Research I have seen on impact tends to be muted at best and studies in HE like this one (Benoit, 2022) suggest potential detrimental impacts. IWBs for me are emblematic of much of what I feel is often wrong with the way ed tech is purchased and used. Big companies selling big ideas to people in educational institutions with purchasing power and problems to solve but, crucially, at least one step removed from the teaching coal face. Nevertheless, because of my role at the time (‘ILT programme coordinator’, thank you very much) I did my damnedest to get colleagues using IWBs interactively and at all (I was going to say ‘effectively’) other than as a screen until I realised that it was a pointless endeavour. For most colleagues the IWB was a solution to a problem that didn’t exist.

A problem that is better articulated is about the extent of engagement of students coupled with tendencies towards uni-directional teaching and passivity in large classes. One solution is ‘Clickers’. These have been kicking around since the 1960s in fact and foreshadowed modern student / audience response systems like Mentimeter, still sometimes referred to as clickers (probably by older generation types like me). Research was able to show improvements in engagement, enjoyment, academic improvement and useful intelligence for lecturing staff (see Kay and LeSage, 2009; Keough, 2012; Hedgcock and Rouwenhort, 2014) but the big problem was scalability. Enthusiasts could secure the necessary hardware, trial use with small groups of students and report positively on impact. I remember the gorgeous aluminium cases our media team held containing maybe 30 devices each. I also recall the form filling, the traipse to the other campus, the device registering and the laborious question authoring processes. My enthusiasm quickly waned and the shiny cases gathered dust on media room shelves. I expect there are plenty still doing so and many more with gadgets and gizmos that looked so cool and full of potential but quickly became redundant. BYOD (Bring your own device) and cloud-based alternatives changed all that of course. The key is not whether enthusiasts can get the right kit but whether very busy teachers can get it and the results versus effort balance sheet firmly favours the former. There are of course issues (socio-economic, data, confidentiality, and security to name a few!) with cloud-base BYOD solutions but the tech is never going to be of the overnight obsolete variety. This is why I am very nervous about big ticket kit purchases such as VR headsets or smart glasses and very sceptical about the claims made about the extent to which education in the near future will be virtual. Second Life’s second life might be a multi-million pound white elephant.

Finally, one of the big buzzes in the kinds of bubbles I live in on Twitter is about the ‘threat’ of AI. On the one hand you have the ‘kid in the sweetshop’ excitement of developers marvelling at AI text authoring and video making and on the other doom-mongering teachers frothing about what these (massively inflated, currently) affordances offer our cheating, conniving, untrustworthy youth. The argument goes that problems of plagiarism, collusion and supervillain levels of academic dishonesty will be exacerbated massively. The ed tech solution: More surveillance! More checking! Plagiarism detection! Remote proctoring! I just think we need to say ‘whoa!’ before committing ourselves to anything and see whether we might imagine things a little differently. Firstly, do existing systems (putting aside major ethical concerns) for, say, plagiarism detection, actually do what we imagine them to do? They can pick up poor academic practice but can they detect ‘intelligent’ reworking? The problem is: How will we know what someone has written themselves otherwise? But where is our global perspective on this? Where is our 21st century eye? Where is acknowledgement of existing tools used routinely by many? There are many ways to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ and different educational traditions value different ways to represent this. Remixes, mashups and sampling are a fundamental part of popular culture and the 20s zeitgeist. Could we not better embrace that reality and way of being? Spellcheckers and grammar checkers do a lot of the work that would have meant lower marks in the past but we use them now unthinkingly. Is it such a leap to imagine positive and open employment of new tools such as AI? Solutions to collusion in online exams offer more options it seems: 1. Scrap online exams and get them all back in huge halls or 2. [insert Mr Burns’ gif] employ remote proctoring. The issues centre on students’ abilities to 1. Look things up to make sure they have the correct answer and 2. Work together to ensure they have a correct answer. I find it really hard not see that as a good thing and an essential skill. I want people to have the right answer. If it is essential to find what any individual student knows, our starting point needs to be re-thinking the way we assess NOT looking for ed tech solutions so that we can carry on regardless. While we’re thinking about that we may also want to re-appraise the role new tech does and will likely play in the ways that we access and share information and do what we can to weave it in positively rather than go all King Canute.

Benoit, A. (2022) Investigating the Impact of Interactive Whiteboards in Higher Education. A Case Study. Journal of Learning Spaces

Hedgcock, W. and Rouwenhorst, R. (2014) ‘Clicking their way to success: using student response systems as a tool for feedback.’ Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education,

Kay, R. and LeSage, A. (2009) ‘Examining the benefits and challenges of using audience response systems: A review of the literature.’ Computers & Education

Keough, S. (2012) ‘Clickers in the Classroom: A Review and a Replication.’ Journal of Management Education

‘Why might students not always act with academic integrity?’ We tried asking them

Guest post from Dr Alex Standen (UCL Arena). I am grateful to my colleague Alex for the post below. I can, I know, be a little bit ‘all guns blazing’ when it comes to issues of plagiarism and academic integrity because I feel that too often we start from a position of distrust and with the expectation of underhandedness. I tend therefore to neglect or struggle to deal even-handedly with situations where such things as widespread collusion have clearly occurred. It is, I accept, perhaps a little too easy to just shout ‘poor assessment design’! without considering the depth of the issues and the cultures that buttress them. This post builds on an in intervention developed and overseen by Alex within which students were asked to select the most likely cause for students to do something that might be seen as academically dishonest. The conclusions, linked research and implications for practice are relevant to anyone teaching and assessing in HE.

———————-

In 2021, UCL built on lessons learnt from the emergency pivot online in 2020 and decided to deliver all exams and assessments online. It’s led to staff from across the university engaging with digital assessment and being prompted to reflect on their assessment design in ways we haven’t seen them do before.

However, one less welcome consequence was an increase in reported cases of academic misconduct. We weren’t alone here – a paper in the International Journal for Educational Integrity looks at how file sharing sites which claim to offer ‘homework help’ were used for assessment and exam help during online and digital assessments. And its easy to see why, as teaching staff and educational developers we try to encourage group and collaborative learning, we expect students to be digitally savvy, we design open book exams with an extended window to complete them – all of which serve to make the lines around plagiarism and other forms of misconduct a little more blurry.

We worked on a number of responses: colleagues in Registry focused on making the regulations clearer and more in line with the changes brought about by the shift to digital assessment, and in the Arena Centre (UCL’s central academic development unit) we supported the development of a new online course to help students better understand academic integrity and academic misconduct.

The brief we were given was for it to be concise and unequivocal, yet supportive and solutions-focused. Students needed to be able to understand what the various forms of academic misconduct are and what the consequences of cases can be, but also be given support and guidance in how to avoid it in their own work and assessments.

Since September 2021, the course has been accessed by over 1000 registered users, with 893 students being awarded a certificate of completion. It’s too early of course to understand what – if any – impact it will have had on instances of academic misconduct. What it can already help us to think about, however, are our students’ perspectives on academic misconduct and how in turn we can better support them to avoid it in future.

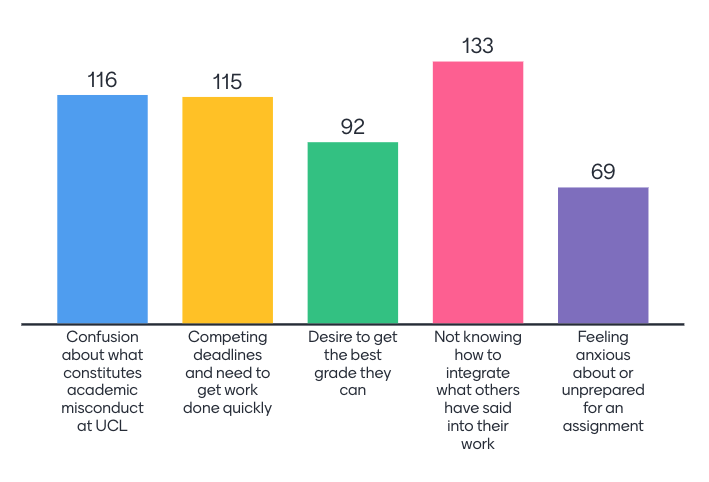

The course opens with a Menti quiz asking participants for their opinions on academic misconduct, posing the question: Why might students not always act with academic integrity? Here are the results (absolute numbers):

What they are telling us is that it is less about a lack of preparation or feelings of stress and anxiety on their part, and more a lack of understanding of how to integrate (academic) sources, how to manage their workload and what academic misconduct can even entail.

Our students’ responses are in line with research findings: studies have found a significant degree of confusion and uncertainty regarding the specific nature of plagiarism (Gullifer and Tyson, 2010) and situational and contextual factors such as weaknesses in writing, research and academic skills (Guraya and Guraya 2017) and time management skills (Ayton et al, 2021).

All of which gives us something to work on. The first is looking at how we plan our assessments over the course of a year so that students aren’t impeded by competing deadlines and unnecessary time pressures. The second is to devote more time to working with students on the development of the academic skills – and it is key that this isn’t exclusively an extra-curricular opportunity. Focusing on bringing this into the curriculum will ensure that it is accessible to all students, not just those with the times and personal resources to seek it out. Finally, as we move to more digital assessments, it is about really reflecting on the design of these to ensure they are fit for this new purpose – and perhaps the first question we should all be asking ourselves is, do we really need an exam?

How effective are your questions?

[listen -10 mins -or read below]

Questions you ask students are at the heart of teaching and assessment but where and how you ask them, the types of questions you ask and the ways you ask them can sometimes be neglected. This is especially true of the informal (often unplanned) questions you might ask in a live session (whether in-person or online) where a little additional forethought into your rationale, approach and the actual questions themselves could be very rewarding. I was prompted to update this post when reviewing some ‘hot questions’ from new colleagues about to embark on lecturing roles for the first time. They expressed the very common fears over ‘tumbleweed’ moments when asking a question, concerns over nerves showing generally and worries about a sea of blank screens in online contexts and ways to check students are understanding, especially when teaching online. What I offer below is written with these colleagues in mind and is designed to be practically-oriented:

What is your purpose? It sounds obvious but knowing why you are asking a question and considering some of the possible reasons can be one way to overcome some of the anxieties that many of us have when thinking about teaching. Thinking about why you are asking questions and what happens when you do can also be a useful self-analysis tool. Questions aren’t always about working out what students know already or have learned in-session. They can be a way of teaching (see Socratic method overview here and this article has some useful and interesting comments on handling responses to questions), a way of provoking, a way of changing the dynamic and even managing behaviour. In terms of student understanding: Are you diagnosing (i.e. seeing what they know already), encouraging speculation, seeking exemplification or checking comprehension? Very often what we are teaching- the pure concepts – are the things that are neglected in questioning. How do we know students are understanding? For a nice worked example see this example of concept checking.

The worst but most common question (in my view). Before I go any further, I’d like to suggest that there is one question (or question type) that should, for the most part, be avoided. What do you think that question might be? It is a question that will almost always lead to a room full of people nodding away or replying in other positive ways. It makes us feel good about ourselves because of the positive response we usually get but actually can be harmful. The reason for it is that when we ask it there are all sorts of reasons why any given student might not actually give a genuine response. Instead of replying honestly they see others nodding and do not want to lose face, appear daft, go against the flow. They see everyone else nodding and join in. But how many of those students are doing the same? How does it feel when everyone else appears to understand something and you don’t? Do you know what the question is yet? See foot of this post to check** (Then argue with me in comments if you disagree).

Start with low stakes questions. Ask questions that ask for an opinion or perspective or to make a choice or even something not related to the topic. Get students to respond in different ways (a quick show of hands, an emoji in chat if teaching online, a thumbs up/ thumbs down to an e-poll or a controversial quotation – Mentimeter does this well). All these interactions build confidence and ease students into ‘ways of being’ in any live taught session. Anything that challenges any assumptions they may have about how teaching ‘should’ be uni-directional and help avoid disengagement are likely to help foster a safe environment in which exchange, dialogue, discussion and the questions that are at the heart of those things are comfortably accepted. Caveat: it is worth noting here that what we might assume if a student is at the back and not contributing will almost certainly have reasons behind it that are NOT to do with indolence or distraction. A student looking at their phone may be anxious about their comprehension and be using a translator, for example They are there! This is key. Be compassionate and don’t force it. Build slowly.

Plan your questions. Another obvious thing but actually wording questions in advance of a session makes a huge difference. You can plan for questions beyond opinion and fact checking types (the easiest to come up with on the fly). Perhaps use something like The Conversational Framework or Bloom’s Taxonomy to write questions for different purposes or of different types. Think about the verbal questions you asked in your last teaching session. How many presented a real challenge? How many required analysis, synthesis, evaluation? Contrast to the number that required (or could only have) a single correct response. The latter are much easier to come up with so, naturally, we ask more of them. If framing the higher order questions is tough on the spot, maybe jot a few ahead of the lecture or seminar. If you use a tool like Mentimeter to design and structure slide content it has many built in tools to encourage you to think about questions that enable anonymous contributions from students.

The big question. A session or even a topic could be driven by a single question. Notions of Enquiry and Problem-Based Learning (EBL/ PBL) exploit well designed problems or questions that require students to resolve. These cannot of course be ‘Google-able’ set response type questions but require research, evidence gathering, rationalisation and so on. This reflects core components of constructivist learning theory.

The question is your answer. Challenging students to come up with questions based on current areas of study can be a very effective way of gauging the depth to which they have engaged with the topic. What they select and what they avoid is often a way of getting insights into where they are most and least comfortable.

Wait time. Did you know that the average time lapse between a question being asked and a student response is typically one second? In effect, the sharpest students (the ‘usual suspects’ you might see them as) get in quick. The lack of even momentary additional processing time means that a significant proportion (perhaps the majority) have not had time to mentally articulate a response. Mental articulation goes some way to challenging cognitive overload so, even where people don’t get a chance to respond the thinking time still helps (formatively). There are other benefits to building in wait time too. This finding by Rowe (1974)* is long ago enough for us to have done something about it. It’s easy to see why we may not have done though…I ask a question; I get a satisfyingly quick and correct response…I can move on. But instilling a culture of ‘wait time’ can have a profound effect on the progress of the whole group. Such a strategy will often need to be accompanied by….

Targeting. One of the things we often notice when observing colleagues ‘in action’ is that questions are very often thrown out to a whole group. The result is either a response from the lightning usual suspect or, with easier questions, a sort of choral chant. These sorts of questions have their place. They signify the important. They can demarcate one section from another. But are they a genuine measurement of comprehension? And what are the consequences of allowing some (or many) never to have to answer if they don’t want to? Many lecturers will baulk at the thought of targeting individuals by name and this is something that I’d counsel against until you have a good working relationship with a group of students but why not by section? by row? by table? “someone from the back row tell me….”. By doing this you can move away from ‘the usual suspects’ and change your focus- one thing we can inadvertently do is to focus eye contact, attention and pace on students who are willing and eager to respond thereby further disconnecting those who are less confident or comfortable or inclined to ‘be’ the same.

Tumbleweed. The worry of asking a question and getting nothing in response can be one of those things that leads to uni-directional teaching. A bad experience early on can dissuade us from asking further questions and then the whole thing develops its own momentum and only gets worse. The low stakes questions, embedding wait time and building a community comfortable with (at least minimal) targetting are ways to pre-empt this. My own advice is that numbers are with you if you can hold your nerve and relaxed smile. Ask a question and look at the students and wait. 30 seconds is nothing but feels like an eternity in such a situation. However, there are many more of them than you and one of them will break eventually! Resist re-framing the question or repeating it too soon but be prepared to ask a lower stakes version and building from there. More advice is available in this easy access article.

Technology as a question not the answer. Though they may seem gimmicky (and you have to be careful that you don’t subvert your pedagogy for colour and excitement) there are a number of in- or pre-session tools that can be used. Tools like Mentimeter, Polleverywhere, Socrative, Slido, Kahoot all enable different sorts of questions to be answered as does the ‘Hot Questions’ function in Moodle that prompted me to re-post this.

Putting thought into questions, the reason you are asking them and how you will manage contributions (or lack thereof) is something we might all do a little more of, especially when tasked with teaching new topics or to new groups or in new modalities.

*Rowe, M. B. (1974). Wait‐time and rewards as instructional variables, their influence on language, logic, and fate control: Part one‐wait‐time. Journal of research in science teaching, 11(2), 81-94. (though this original study was on elementary teaching situations the principles are applicable to HE settings)

**Worst question? ‘Does everyone understand?’ or some such variant such as nodding and smiling at your students whilst asking ‘All ok? or ‘Got that?’. Instead ask a question that is focussed on a specific point. Additionally, you might want to routinely invite students to jot their most troubling point on a post it or have an open forum in Moodle (or equivalent space) for areas that need clarifying.

[This is an update- actually more of a significant re-working- of my own post, previously shared here: https://blogs.gre.ac.uk/learning-teaching/2016/11/07/thinking-about-questions/]

‘Blended by design’ thinking

Read (7 mins) or Listen (11 mins)

The initial response to the Covid-enforced campus closures can be characterised as ’emergency remote teaching’ (ERT) (see Hodges et al., 2020 for detailed discussion of this) and whilst many saw it as a great opportunity to put ‘online learning’ to the test, the rapidity of the shift and the lack of proper planning time meant that this was always going to be hugely problematic. In many ways, conflating ERT with online/ blended teaching has buttressed the simplistic narrat ives we are increasingly hearing: online = bad; in-person = good. This is a real shame but understandable in some ways I suppose. As time went on, I witnessed tons of experimentation, innovation, and effective practice informed by scholarship of teaching and learning. Each of these endeavours signified an aspect of our collective emergence from ERT towards models of online and blended teaching and learning much better aligned to research evidence and, frankly, what experienced online/blended teachers and designers had been arguing and promoting for some time. Will this be reflected in planning for 21-22 and beyond? At UCL, the perspective on the near and medium term future is being framed as ‘blended by design’.

ives we are increasingly hearing: online = bad; in-person = good. This is a real shame but understandable in some ways I suppose. As time went on, I witnessed tons of experimentation, innovation, and effective practice informed by scholarship of teaching and learning. Each of these endeavours signified an aspect of our collective emergence from ERT towards models of online and blended teaching and learning much better aligned to research evidence and, frankly, what experienced online/blended teachers and designers had been arguing and promoting for some time. Will this be reflected in planning for 21-22 and beyond? At UCL, the perspective on the near and medium term future is being framed as ‘blended by design’.

Given ongoing uncertainties AND the growing acceptance of the many opportunities for embracing many of the affordances realised by blended teaching, learning and assessment in HE (particularly in terms of inclusive practice), my feeling is that a focus on ‘by design’ is an important framing, as it counterpoints the implied panicky, knee-jerk (though necessary at the time) ERT and emphasises the positive and nuanced aspect we can now take. In other words, it’s not because of ‘forced compliance’ but because we and our students will benefit. We have more time (though it may not feel like it) to reflect on approaches that work in our disciplines and make informed decisions about how we might remain flexible whilst optimising some of the more effective and welcomed aspects of online tools & approaches and how that can be woven into how we will likewise optimise time in-person. It goes without saying (I think) that ‘blended’ learning can be many, many things but at some level seeks to combine coherently in a single programme or module in-person and online media, approaches and interactions. Such a broad, anchoring definition is helpful in my view. In an institution like UCL, one size will never fit all: we are gloriously diverse in everything so it allows for huge variation in interpretation under that broadly blended umbrella (please excuse my mashed metaphors). All I’m suggesting is we open our minds to other ways than being, and to face, head on, some of the pre-existing issues in conventional HE, especially if our inclination is to ‘get back as to how it was’ as swiftly as possible. With this in mind, I believe it is worth taking a few moments to consider our mindsets in relation to what ‘blended by design’ might mean so I offer below some thoughts to frame these reflections (as someone who has been blending for 20 years or more and has taught fully online programmes for 6 of those):

[the challenges to think about our thinking below have been developed and updated and were originally published as an infographic here]

1. Reality Check

In our enthusiasm to do our best by our students, it is easy to forget that much of what we have done over the last year was catalysed by a global pandemic. We are still learning as we are doing and the fact that students did not necessarily sign up for an education in this form brings all sorts of new demands to both teacher and student. Whilst it is important to listen to and understand frustrations arising from this, we should also recognise th at blending our teaching and assessment practices offers some new potentials but that the workload and emotional demands we have all faced could cloud our perceptions. One positive aspect to think about as we start reflecting, is that most of us are building on what we did last year so the resource development for many of us should be significantly reduced (for example re-use of recorded lectures). The same applies to essential digital skills development and a growing understanding of what constitutes effective practice in blended modes. The following points all seek to underscore these as we plan for next year.

at blending our teaching and assessment practices offers some new potentials but that the workload and emotional demands we have all faced could cloud our perceptions. One positive aspect to think about as we start reflecting, is that most of us are building on what we did last year so the resource development for many of us should be significantly reduced (for example re-use of recorded lectures). The same applies to essential digital skills development and a growing understanding of what constitutes effective practice in blended modes. The following points all seek to underscore these as we plan for next year.

2. What experienced blended practitioners will tell you

The ‘content’ is best made available asynchronously. Students need orienting to clear, inclusive, signposted and accessible resources and activities that are, where possible, mobile-friendly. Face to face time is NOT best used for didactic teaching. Building a community is fundamental. There are a number of points here but all are fundamentals to consider when blending by design. In fact, they’re so important, it may be useful to re-frame them as questions:

a. Is most of the content available asynchronously in the form of audio, video, text?

b. Is that stuff accessible? Not only accessible in terms of inclusive practice but consistently designed, presented and organised so things can be found easily and students know what to do when they get there? So, for example, do videos come with instructions on how much to watch, what to look out for, how to approach the video, how the information will be followed up/ used/ applied?

c. Are face to face sessions (web-mediated or in “meatspace”) optimised for exchange/ dialogue/ discussion/ questioning/ interaction?

d. What have you done pre-programme, pre-module, pre-session and within each module/ session to build community?

3. Different starting point; different focal point

(To generalise massively!) Content as ‘king’ drives a lot of learning design in HE but, whilst it remains fundamental (of course), we need to reconsider its pre-eminence. Students who have chosen a campus degree are craving on-campus time but we need to be alert to what is being craved here: The company of peers; the proximity of experts. Instead of framing our thinking and actions based on a big lecture or lengthy ‘delivery’ and knowledge-based outcomes we need to open multiple channels of communication first. Another way of looking at this might be to consider typical prior learning experiences and other influencers on expectations of a ‘higher ‘ education. Most, if not all, of our students will know how to approach conventional teaching (a room, focussed on 1 person at the front, usually with a board) and can adapt to environments that have disciplinary specificity (labs, field work) because these fall within their expectations. New pedagogic approaches and differing or unexpected modalities challenge them to learn to ‘be’ in those spaces. We need to guide them. It may seem obvious to us but until we spell out ways of being in novel environments through our words and modelled actions we may be disappointed with levels of engagement.

fundamental (of course), we need to reconsider its pre-eminence. Students who have chosen a campus degree are craving on-campus time but we need to be alert to what is being craved here: The company of peers; the proximity of experts. Instead of framing our thinking and actions based on a big lecture or lengthy ‘delivery’ and knowledge-based outcomes we need to open multiple channels of communication first. Another way of looking at this might be to consider typical prior learning experiences and other influencers on expectations of a ‘higher ‘ education. Most, if not all, of our students will know how to approach conventional teaching (a room, focussed on 1 person at the front, usually with a board) and can adapt to environments that have disciplinary specificity (labs, field work) because these fall within their expectations. New pedagogic approaches and differing or unexpected modalities challenge them to learn to ‘be’ in those spaces. We need to guide them. It may seem obvious to us but until we spell out ways of being in novel environments through our words and modelled actions we may be disappointed with levels of engagement.

4. C Words

If social communication is fostered first then opportunities for collaboration, creation and co-creation linked to the content and in an uncertain and unfamiliar context are more likely to follow.

5. What’s your portal?

Your Virtual Learning Environment may be the logical launch point for your resources but as you integrate other tools and settings (webinars? labs? visits? video content? social media?) you may find your are posting notifications and guidance in lots of places. Stick with one portal and launch all from there. Students need to know where to go.

integrate other tools and settings (webinars? labs? visits? video content? social media?) you may find your are posting notifications and guidance in lots of places. Stick with one portal and launch all from there. Students need to know where to go.

6. No point recreating the wheel (as they say)

Before you make a resource or record a video check to see whether: a. You have done something before you could adapt b. Colleagues have something or are working on something similar or c. You can find something you could use in whole or part online. Find clear ways to link to/ share these and signpost explicitly. There’s a big difference between simply posting a few YouTube links and weaving directions, narratives and questions around those videos and then sharing them of course.

you could adapt b. Colleagues have something or are working on something similar or c. You can find something you could use in whole or part online. Find clear ways to link to/ share these and signpost explicitly. There’s a big difference between simply posting a few YouTube links and weaving directions, narratives and questions around those videos and then sharing them of course.

7. Golden rules

With ‘flipped’, self-access content that students will discuss/ use/ apply later you should be thinking of short, bite-size chunks of information. What are the ‘threshold concepts’? Don’t worry about high-end production in the first instance or the odd cough or interruption – these are both expected and human. If you have curated a lot (see previous point) think even more about how and when students will connect with you.

8. On and off campus connections

Whether time and space for face to face meeting is available or not, office hours, tutorial times, feedback slots and seminars need scheduling. The more this can be factored in the better. NOT scheduling lecture watching time makes sense (offers choice/ flexibility etc) but recognising that things work better within weekly chunks as far as planning activity and making connections is concerned. So, for example, I might ask students to watch videos on topic X sometime on Monday or Tuesday before attending an applied lab session on the Wednesday (I need to find out if there is research data on this as this is purely from personal experiences). With groups who are geographically widespread, fostering time-zone specific communities of practice will really help.

feedback slots and seminars need scheduling. The more this can be factored in the better. NOT scheduling lecture watching time makes sense (offers choice/ flexibility etc) but recognising that things work better within weekly chunks as far as planning activity and making connections is concerned. So, for example, I might ask students to watch videos on topic X sometime on Monday or Tuesday before attending an applied lab session on the Wednesday (I need to find out if there is research data on this as this is purely from personal experiences). With groups who are geographically widespread, fostering time-zone specific communities of practice will really help.

9. If you care they know it!

Insecurities students have about completing studies, technical abilities, time available etc. can be ameliorated significantly when we use time to connect, to show willing, to be available. No-one expects teachers to be online/blended education experts overnight but there is a growing expectation that we will have learned from the inspiring (and bitter) lessons of the last year or so and reflect that in the way we design and facilitate teaching, learning and assessment.

ameliorated significantly when we use time to connect, to show willing, to be available. No-one expects teachers to be online/blended education experts overnight but there is a growing expectation that we will have learned from the inspiring (and bitter) lessons of the last year or so and reflect that in the way we design and facilitate teaching, learning and assessment.

10. By design

To acknowledge, reflect on and then act accordingly means we are doing ‘by design’. Starting with the principles above is actually a lot further ahead than the initial, thrown together responses many were obliged to adopt last year. The blend is inevitable but a pedagogically- informed, compassionate and effective blend is more desirable.

Ungrading: a continuum of possibilities to change assessment and feedback

Listen (11 mins) or read (7 mins)

Slides from Digitally Enhanced Webinars event July 13th 2022

Introduction

I have recently had a few interesting conversations about how our approaches to teaching and assessment in higher education might change post-Covid and it seems apparent that ‘consensus’ is unlikely to be the defining word as we move forward. In a few of those instances I was talking about ‘ungrading’ and, judging by the more dismissive responses, I feel that a fuller understanding of what ungrading could be might help challenge some of my interlocutors’ assumptions and pre-judgements. In this post, I will start with a few provocations that I’d urge you to commit agreement or disagreement to before moving on. I will then offer a brief definition followed by some examples from my own practice and then a rationale with some links to other online articles (that deal with this topic more thoroughly and from a position of much greater expertise) before offering a rudimentary continuum of possibilities all of which can broadly sit under ungrading as an umbrella term.

Yes or no?

- It is possible for practiced teachers/ lecturers to distinguish the quality of work to a precision of a few percentage points

- Double marking will usually ensure fairness and reliability

- For the purposes of student summative assessment, feedback is synonymous with evaluation

- Grades (whether percentage scales or A-E) are useful for teachers and students

- Individual teachers/ lecturers have little or no agency when it comes to making decisions about how to grade or whether to grade

If you said mostly ‘yes’ then you are likely to be harder to persuade but please read on! I’d very much like to hear reasoned objections to the arguments I try to pull together below. If you said mostly ‘no’ then I would like to hear about your ungrading activities, ideas or, indeed, ongoing reservations or obstacles.

Ungrading

As I mention above, ungrading is not a single approach but a broad range of possible alternative approaches and ways of seeing assessment and feedback. The reason I posed the yes/ no statements above was because the first prerequisite to trying an ungrading process is to hold (or be open to) a sentiment or value that questions the utility and effectiveness (and ubiquity) of grades on student work. Fundamentally, ungrading is, at one end of the scale, completely stopping the process of adding grades to student work. A less radical change might be to shift from graded systems to far fewer gradations such as pass/ not yet passed (so called ‘minimal grading’). A ‘dipping the toes’ approach might include more dialogue with students about their grades, self and peer assessment or grade ‘concealment’ as part of a process to encourage deeper connection with the actual feedback. Wherever ungrading happens on this continuum, it doesn’t mean not collecting information about what students are doing. By eschewing grades and rigid (supposedly measurable) criteria we open opportunities for wider, qualitative, multi-voiced narratives about what has been achieved.

My toe dipping

In my previous role I was lucky enough to work on one of the only post grad (PG) programmes across the whole university that did not use percentage grades. Instead, all summative work was deemed pass or fail. The reason for this was because my students were my colleagues studying for a PG Certificate in Teaching in HE. To grade colleagues was seen as problematic for all sorts of reasons and even discourteous. One senior colleague said it would open a can of worms to grade colleagues who would question grades on all sorts of bases. This immediately raises several questions:

- Why is grading discourteous to colleagues but not to ‘normal’ students?

- How did their status change the degree to which we evaluated (labelled?) them?

- If pass/ fail worked OK (the only student/ colleagues who expressed disappointment at only having pass/ fail were high fliers it should be noted) and they achieved these qualifications, why wasn’t that happening on other qualifications?

- Even if only appropriate with ‘professional’ students, why wasn’t it the default on, say, PG counselling programmes?

I pushed the ungrading a step further by de-coupling the previous ‘gatekeeping’ aspect of lesson observations from the graded assessment process (each had been deemed pass or fail to that point), by removing grading from formative work and by modifying the language used on first submission summatives to pass/ not yet passed.

I have also used audio and video feedback and sometimes coupled that with grade discussions/ negotiations and on others with embedding the grades within a multimedia response (harder to skim or ignore than text!). The biggest barriers in both instances were not the students but departmental and institutional pressures to conform to routine practice.

So why do it?

“When we consider the practically universal use in all educational institutions of a system of marks, whether numbers or letters, to indicate scholastic attainment of the pupils or students in these institutions, and when we remember how very great stress is laid by teachers and pupils alike upon these marks as real measures or indicators of attainment, we can but be astonished at the blind faith that has been felt in the reliability of the marking systems” (Finkelstein, 1913 – yes, 1913)

There are two ways of perceiving the above quote I suppose: 1. The utility of grading has won through. Over a hundred years on, their use is still ubiquitous so surely that’s evidence enough that Finkelstein was mistaken or 2. Once we get stuck in our ways in education it takes a monumental effort to change the fundamentals of our practices (cf. examinations and lectures).

Jesse Stommel reflects on the ubiquity and normalisation thus:

“Without much critical examination, teachers accept they have to grade, students accept they have to be graded, students are made to feel like they should care a great deal about grades, and teachers are told they shouldn’t spend much time thinking about the why, when, and whether of grades. Obedience to a system of crude ranking is crafted to feel altruistic, because it’s supposedly fair, saves time, and helps prepare students for the horrors of the “real world.” Conscientious objection is made to seem impossible.” (Stommel, 2018)

A century apart, both are objecting on one level to the claims (or assumptions) made in defence of grading: That they can provide accurate and fair measures; that there is no viable alternative; that they somehow prepare students for life after study. Although I admit I have not made a systematic review of the literature, it does seem much easier to find compelling research to suggest that grading has all sorts of reliability problems. Hooking back to my own (dis)interest in judgemental observations on the PG Cert HE, Ofsted (Governmental body responsible for overseeing standards in schools in England), the epitome of graded judgements, were eventually persuaded that the judgements their inspectors made about lesson observations were neither valid nor reliable. If such a body has issues with trained inspectors’ abilities to make fair judgements on a graded scale, it makes me wonder why similar discussions are not happening in that same body about teachers’ abilities to make fair, valid and reliable judgements of their students. One argument I have read to counter this is that it’s the best system we have for allocating places and deciding who is most worthy of merit – this is hardly a glowing accolade. In addition to this:

“ Grades can dampen existing intrinsic motivation, give rise to extrinsic motivation, enhance fear of failure, reduce interest, decrease enjoyment in class work, increase anxiety, hamper performance on follow-up tasks, stimulate avoidance of challenging tasks, and heighten competitiveness” (Schinske & Tanner, 2014)

And all this BEFORE we have even thought about implicit bias, the skewing of grading systems to favour elites and other prejudicial facets that are embedded in the assumptions that buttress them. Many esteemed experts in assessment and feedback are unequivocal in their concerns over grading and/ or the way grading is done. Chris Rust, for example argues:

“much current practice in the use of marks and the arrival at degree classification decisions is not only unfair but is intellectually and morally indefensible, and statistically invalid” (Rust, 2007)

For more detailed critique of the impact of grading I’d recommend Alfie Kohn’s website and especially this article titled ‘from degrading to de-grading’ and for a worked alternative see Jesse Stommel’s account and rationale here. For a forensic consideration of grading, including some interesting historical context I’d also recommend the Schinske and Tanner article.

Deep end or paddling: an ungrading continuum

So, how might we do something with this? Without actually changing anything I would argue a good starting point would be to develop and share a healthy scepticism about the received wisdom and convention (of grading as well as many other seemingly immutable educational practices). If we read more of the research and feel compelled to act but constrained by the culture, the expectations of students, by the demands of awarding bodies and so on perhaps we could experiment with removing grades from one or two pieces of work. Alternatively, we might begin to change the ‘front and centre’ aspect of grades by, for example, concealing them, within feedback or inviting students to determine or negotiate grades based on their feedback. Going further we might involve students more in determining summative grades as well as assisting us in defining criteria for success at the outset. We may decide to shift to a minimal grading model or elect to grade only major summatives or offer a single grade across an entire module (or year?) or, going further still, use outcomes of peer review and student self-assessment to determine grades. We may invite (with justifications) students to grade themselves (see Stommel example) or perhaps explore the possibilities of offering programmes that do not grade at all. As Stommel (2018) says:

If you’re a teacher and you hate grading, stop doing it.

- Finkelstein IE. (1913) The Marking System in Theory and Practice. Baltimore: Warwick & York

- Rust, C. (2007) Towards a scholarship of assessment, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32:2, 229-237

- Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching more by grading less (or differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159-166.

- Stommel, J. (2018) How to ungrade. Available at: https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-ungrade/

- See also

- Blum, S. D., & Kohn, A. (2020). Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (And What to Do Instead). West Virginia University Press.

- Elbow, P. (1997). Grading student writing: Making it simpler, fairer, clearer. New directions for teaching and learning, 1997(69), 127-140.

- Winstone, N., & Carless, D. (2019). Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach. Routledge. (Broader, contemporary issues around feedback and assessment design)

- Ungrading FAQs https://www.jessestommel.com/ungrading-an-faq/