[listen 12m 35s or read below)

With apologies to both Bridget Fonda and to the killer on the left/ right etc, this was the title of my keynote at Kingston’s ‘Future of Learning’ conference in June 2021 and revamped for FRA in January 2022 and below is my related tuppenceworth in the form of 10 provocations on what we ought to be doing and avoiding as we prepare for at least one more year of uncertainty and change in higher education. I have been teaching online for 5+ years and integrating all things digital for a lot longer. Another way of saying that is I have learnt a lot of things the hard way by getting them wrong, wasting efforts unnecessarily and realising, too slowly, things I’d probably now consider to be obvious. Everything I say needs to be set against that background. My position and my perspectives are informed by this. I did (and continue to), however, spend a lot of time supporting colleagues from across the disciplines and professional services and across the digital confidence, capabilty, enthusiasm and kit spectrums during and subsequent to the pivot online.

1. “Forced compliance” of 20-21 shouldn’t define how we understand online/ blended/ hybrid (or whatever the heck it’s called now)

screenshot from twitter @mart_compton showing image with post it notes

When I think about the last year it’s a real mixed bag. If I can push aside the awful bits and focus on the work, I still find that the reflections are necessarily blurred with family/ personal stuff, not least because my daughter (age 9) was at home for a lot of it. She and I worked at either ends of the kitchen and my day was salt and peppered with notes like these asking me to keep the volume down. This is emblematic in my mind of the necessarily different ways of working and being to what was ‘normal’. This tiny inconvenience is insignificant compared to some of the impacts felt across the sector by many academic staff and students, often struggling to find adequate space and kit to work with. The suddenness and the necessity combined to create a situation where the decision to teach in these ways was largely out of our hands. Many have argued that the silver lining of the dark cloud that is still very much part of our lives is the way the pandemic catalysed advances in digital confidence and competence unimaginable in ‘normal’ times. The other side of this of course is how the experiences of some teachers and students tainted many people’s perceptions of what an online or blended education could be.

2. Be (REALLY) honest with ourselves about what worked, what didn’t, what we developed and what we still need

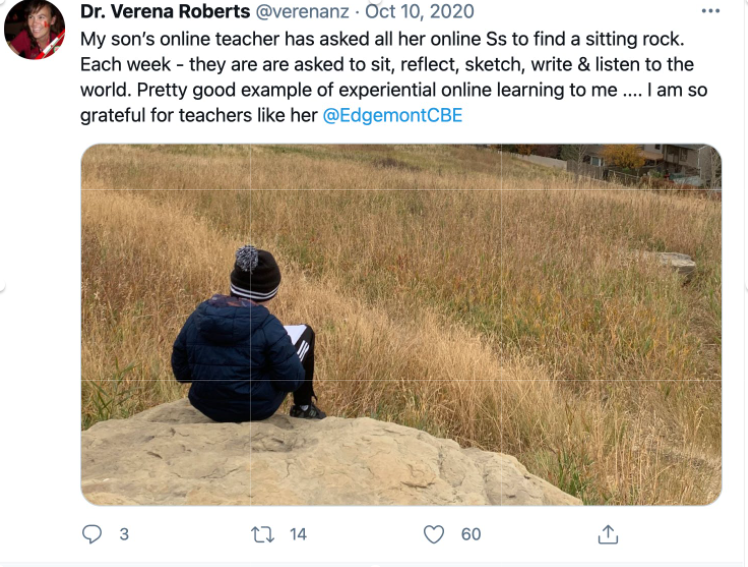

screenshot from twitter-@verenanz showing boy on a rock

This (for me at least) is one of those things that sounds easy and obvious but is actually quite challenging. Do we ever give ourselves enough time to properly think? In the context of point 1 above, can we properly think without some form of scaffold and/ or mediation? Do we have enough information to think usefully (and with opportunities for discursive exploration) to reflect with one eye looking back and another looking forward? This image really struck me during the lockdown. It’s from an academic in Canada (Dr. Verena Roberts: image shared with permission) who shared a picture of her son on his ‘reflection rock’. Time for reflection being built into the lockdown school day was a powerful reminder from a very different context of how learning does and should happen beyond those times we are ‘in control’. So much was represented in that image: What is possible when we relinquish control; valuing the affective; encouraging liberty, creativity and independence. We need to give our students space and tools to reflect but not forget either that we also need the same opportunities.

3. We need to push against binary thinking and simplistic narratives

Those that are not so good at reflecting or embracing nuance or those with strong vested interests in a swift return to ‘normal’ may be inclined to push, echo or sympathise with simplistic narratives: online = BAD; in person = GOOD. From the very start of the pandemic I heard (and almost certainly said myself) ‘we are not the Open University’ but that shouldn’t stop us from being open to models they have developed and honed over decades of offering remote and online education. Respecting and heeding wisdom from OU colleagues and practise, then or looking ahead, does not mean we want to occupy their ground or to become them. To suggest that as a way of closing down discussion is, to my mind, often a symptom of exclusionary thinking. Widening participation means developing an understanding of some of the positive aspects remote connection enabled for significant numbers of our students. By casting light on possibilities otherwise masked by years of convention we have revealed what is possible and the after-image of that has burned deep however swiftly we try to turn off the light. The best we can offer is impacted by so many variables but we do know that disciplinary contexts help define what we do; that one size solutions would only ever be a temporary fix and that online and remote options in education exist for a reason. Accepting this in reasoned discussions about what post-pandemic pedagogies look like is essential.

4. Lectures and exams. Always elephants in the room; only a lot bigger now

Henry of Germany delivering a lecture to university students in Bologna by Laurentius de Voltolina (public domain)

I expect most have seen before this classic 14th century image (a screen grab from a very early iteration of Lecturecast) of students snoozing or chatting in the lecture and the one being distracted by a smart phone under the bench. They think Henry hasn’t noticed of course but it’s amazing what you can see from the front. The pandemic has certainly given us pause for thought about the lecture as default teaching modality (in many places) and, likewise, the exam as default summative assessment (in many places) has been challenged, not least by emerging evidence of attainment gaps closing due to assessment modifications.

I am NOT advocating (like some) the end of the lecture completely BUT it is hard to argue that content-dense, one size fits all pedagogies AS DEFAULT really help us realise the EDI ideals that institutions present with great fanfare as defining the what University X or Y is all about.

What I am an advocate of is (cf. point 3 above) a push back against binary thinking on the often polarising debate about lectures and exams, for much more nuanced thinking and openeness to new ways of working. Of course, if we conclude that breaking with convention would be better then we need to work out ways to resource and support that. Failing to change because a. we have always done it that way or b. it’s too expensive are fallacious arguments because they appeal to tradition and cost (according to one of my teachers from secondary school). If it’s worth doing then we need to work out how to do it.

5. Replicating face to face models is not optimising affordances of digital stuff

postcard drawn by Jean-Marc Côté in early 20th century depicting a video telephone system

This image is called ‘correspondence cinema’ and is one of a series of cigar box inserts and post cards created between 1899 and 1910 that imagined the year 2000. Most were way off but a few hit the mark- this one I like because it foreshadows Zoom and Teams but also reminds me that one of the big OBVIOUS conclusions many reached at the start of the pandemic was how we could use these tools to replicate what was being lost in lockdown- the face to face session. For lots of reasons though this is less than optimal and is NOT actually a feature of well- planned, invested in, developed online programmes. What should the features be then? Well, of course, there’s a long answer to that but: Along with more emphasis on asynchronous ‘content’ and optimising live, connection time for interaction, dialogue, debate we need to think carefully about our goals, our contexts and where we can use digital options can offer something different, new, better or can give improved access.

6. Start from a position of compassion, trust and openness

A starting point, now more than ever, needs to be one of compassion and trust. We and our students are dealing with the trauma of pandemic. We (and they) have adapted to new pedagogic approaches and will now be adapting once again. At a local level this means building in time for community building and building on the affordances offered by both analogue and digital ways of connecting, supporting and simply ‘being there’. More broadly I would argue that we need to resist narratives that divide; push back against the us and them framing of lecturers and students; resist too the pressures from enterprises that profit from us surveilling our students. Plagiarism detection wasn’t a thing when I was student- I am sure copying was – but the world somehow muddled through. I think it gives a false sense of rigour and can make us less likely to employ tactics previously used (for example, ad hoc mini vivas).

7. Grading can be degrading: ‘Ungrading’ and/or digital assessment and feedback can have powerful impacts

I talk about this here so will resit the urge to thump this tub again!

8. Shiny things (AI, VR, robotics, IoT) are a thing but not THE thing!

I see part of my role as trying to re-assure those colleagues who sometimes feel like the expectations are way up there in terms of what they should be doing- in some ways ‘shiny things’ can be distractors (most are NOT doing this stuff) and actually act as de-motivators. Innovation should be seen as ipsative; that is, it is relative to your own prior approaches. I talk more about his here.

9. Why so much writing? Value multi-modal, value listening, value silence.

At school- imagined future post card produced in the period 1900-1910 – often credited to Jean-Marc Côté (public domain)

In this post I ask why it is that the communication skill most of us use least (IRL) is the one that is overwhelmly pre-eminent in our (UK) education system. What will it take to offer more audio-visual options and content? My own videos are often rough round the edges though I tend to favour audio options over video anyway. Also, as someone who talks a lot and is very opinionated, I know how hard it is to factor in thinking and wait time when you’re on a roll and, for many, that difficulty was only exacerbated in remote, online interactions. This is one area where (assuming we are compelled by the need to value listening and silence more) is something we can blunt force train ourselves to do.

10. Value the student voice but don’t confuse want with need

I hope this last one speaks for itself- sometimes what students (indeed, all humans) WANT is not necessarily what they NEED in a given context. Before you ‘ah ha!’ me by referring me back to point 6 above, I would re-iterate that I am stressing here the value of disciplinary AND pedagogic expertise. I’m definitely not saying we always know best but, in the same way a patient might have some ideas about what is troubling them because they can use Google or know someone with similar symptoms does not mean medical professionals ignore their own expertise. If students are pushing back against well thought through approaches or loud voices are demanding X when you have planned Y it may be because it’s not what they expect or hoped for. Maybe, therefore, we can do more to rationalise our approaches and share the pedagogic approaches we are taking. Anything that gets us talking with one another and with our students about what we are doing and why is likely to help.