On the 18 January I attended the University of East London Learning and Teaching Symposium on ‘Contemporary issues in Higher Education’. University of East London (UEL) are a ‘careers first’ University, and have 40,000 students from over 160 different countries, 70% of their students are from the global south and 57% of UEL students are the first in their family to attend university. The event was held just up the road from UCL East at the University Square Stratford Campus and was opened by Professor Bugewa Apampa, Pro Vice-Chancellor of Education and Experience. Professor Apampa noted that assessment and feedback are integral to many of the issues experienced in Higher Education today. She called for participants to work on widening participation, and reducing the achievement gap. She emphasized the importance of making higher education relevant, inclusive, and fostering a love of learning. The talks that I went to focused on feedback, authentic assessment, and student partnerships.

Designing effective feedback

“No matter how quick, how detailed, or how high-quality the feedback our students receive, feedback can never be effective unless they use it,”

Nash & Winstone (2017)

The first keynote was on ‘The elusive mechanics of effective feedback’, from Dr Robert Nash, Reader in Psychology at Aston University and Head of Psychological Research at the National Institute of Teaching

What causes feedback to be effective? Across Universities right now there are numerous initiatives to improve the content and delivery of feedback, but do these interventions change learners’ behaviour and how is the effectiveness of feedback evaluated? Dr Nash’s research has indicated that students do not always engage with or remember feedback, and in fact the lower the grade the less likely they are to open and read the feedback.

Should efforts across HE to improve the quantity and speed of feedback perhaps be redirected into making sure that feedback is being used effectively by students?

Drawing on his recent joint article ‘Toward a cohesive psychological science of effective feedback’ (2023), Dr Nash made a call for sharing evidence between different disciplinary silos to develop more rigorous and scientific research on how students receive and use feedback.

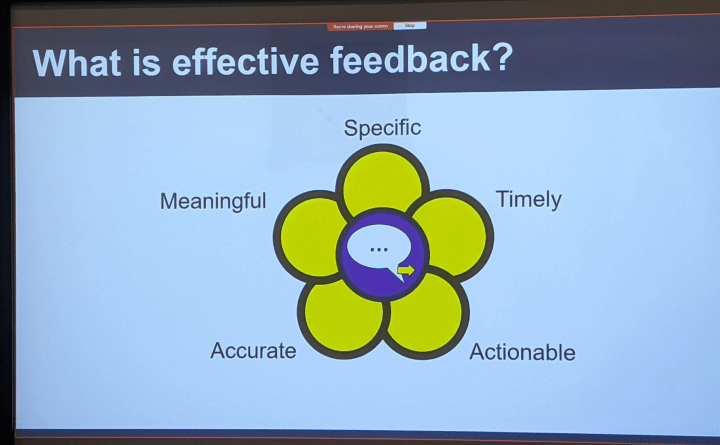

Studies on effective feedback in education, focus on it being specific, meaningful, timely, actionable, and accurate. Studies within behavioural health, psychology, occupational health, and behavioural medicine have illustrated that people are more receptive to feedback when they feel invested in and in control of their own performance (they can and are eager to do something about the feedback), they feel secure in their own self-worth and can identify and critically appraise their immediate reactions. Transferring, this to feedback in Higher Education, means that we need to think about the emotional aspect of feedback as well as what we are telling students to do. We need to develop students feedback literacy through conversations about the importance of feedback and the process of receiving and making use of it. It is important to acknowledge that feedback can be difficult to receive and we need to work on getting students engaged in the process so that they want feedback.

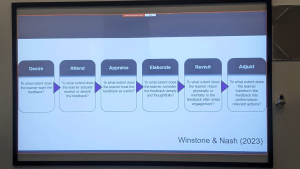

Using the framework, developed with Professor Naomi Winstone, Dr Nash drew out the different questions that we should be asking ourselves about the various process of feedback. For example, are students open to feedback and are they engaging, valuing, and understanding feedback once it is given to them? Are students able to ‘feed-forward’ and apply feedback to other tasks and do they remember the feedback they were given? Finally, do they change their behaviour and make efforts to adjust according to the feedback they receive?

By breaking down the various stages in the feedback process and focusing on what students do after receiving feedback we are better placed to ask the right research questions and design interventions to ensure we are providing effective feedback. Programme design is critical in this process to review if students are given opportunities to review and apply feedback, are we providing the right feedback at the right time to help students make links between modules?

Dr Nash finished with some suggestions on how to develop students’ feedback literacy including:

- Reflecting on the feedback experience: Giving examples from feedback in your own practice (peer review, teaching observations) – how you engaged with it, how it was difficult.

- Embedding examples of the science of feedback into the curriculum.

- Using learning analytics to see if students are reading feedback and following up to find out if not why not?

- Separating feedback from grades.

- Task-orientated encoding of feedback – getting students to engage with feedback as an activity. What do they do with the feedback?

- Task-orientated retrieval of feedback – getting students to reflect and review feedback – can they remember it?

- Structured goal-setting activities – a to-do list created after receiving feedback.

- Engaging with feedback in class (DIRT – dedicated reflection and improvement time in, used in schools and could be brought into HE).

Peer feedback

The practical issues associated with peer assessment and authentic assessment were explored in the breakout sessions I attended. Both presentations highlighted the importance of involving students in the assessment process and building in discussions on the rationale and aims of assessment design.

Can students fairly assess their peers? Transparency in education, Dr Carol Resteghini, UEL

Dr Restehini discussed her experiences with peer assessment on a module in physiotherapy with 100 students. In this module, students are given a practical assessment to ensure they can apply the theoretical concepts that they are taught in neuroscience. The cohort is made up of two groups, one of full-time students and one of practice-based students who are working in the field and come in once a week to study. Dr Restehini inherited the module, and the first iteration of the peer assessment was not a success, students were annoyed about being asked to do ‘the teacher’s job’ and lots of moderation was needed to mitigate students colluding to award each other high marks.

Adjustments were made to the process. Students were involved by being asked to review the assessment marking grid and employers were also consulted to ensure that it was based on workplace processes. All students were given access to the bank of assessment questions at the start of the course. Student groups and assessment questions are allocated at random on the day of assessment. Groups of 4 were asked to take it in turns to complete a practical task based on a scenario from the assessment questions. The students then independently award marks (including for their own work). After awarding marks they must share them with the rest of the group and provide a brief explanation as to why. Once everyone has completed the tasks, they have a longer discussion with the tutor outlining their decisions and agree a mark for the entire group for completing the process.

Evaluation

The students were asked for feedback on the process before and after the assessment and ahead of marks being released. Surprisingly the practice-based students were much more negative and apprehensive about the process than the full-time students. They were also less confident about their performance, with self-assessment marks for apprentices being below their performance. Moderation for both groups was minimal although the full-time students were more confident about their abilities with self-assessment marks slightly higher than the final grade received. Despite high average marks for both cohorts, confidence levels of all students remained unchanged and the NSS scores for feedback were still low. More work needs to be done on exploring the different experiences between the two cohorts and signposting the benefits of assessing peers and giving feedback in the workplace.

Authentic assessment

Designing an authentic assessment ‐ “The Apprentice” task. Edessa Gobena and Sophia Semerdjieva, University of East London

The second talk was on designing assessment for a module teaching the biology of disease and clinical diagnosis on the MSc in Biomedical Science. The course has 203 students, 99% of which are international, with about half aged 21-24. In the academic year 22/24, the module pass rate was 94% but with four written tasks the module leaders believed that students were being over-assessed and this was leading to a high workload for staff and students. They wanted to avoid recall and abstract learning and motivate students to apply their knowledge to collaborative tasks that required sharing ideas, opinions, and team-based learning.

The moved to two components, giving students a group task worth 50%. All students are put into groups of 5 and given a task to pitch for a contract to deal with a disease in a field clinic. They needed to work together to record a 15-minute presentation, with 3 minutes from each team member and submit it to Turnitin for group and generic feedback. 5% of the marks were based on each group completing and signing a group contract which contained ground rules, policies and procedures including how often they would meet etc. All students were asked to attend a workshop on the teamwork contract and were given different scenarios that may come up when working in groups and asked to discuss how they would resolve them.

Evaluation

Despite the assessment being on 21 December only 9 (5%) of students were absent and only 1 student failed. The previous coursework assignments had very high levels of non-engagement with multiple resits, so this was a huge improvement. Students were asked to complete a survey on teamwork satisfaction and self-assessment of their learning gains before they received their marks. Students believed they gained skills but there were some issues and not everyone enjoyed working in a team. The course team plans to do more work on training students in conflict resolution. The team used https://salgsite.org/ to measure students learning gains, with 54% stating that they had made a great gain and 25% a good gain. Evaluation of the qualitative feedback still needs to take place, but the plan is to involve industry partners in future iterations and find out more about student backgrounds.

Keynote: ‘Moving towards more authentic assessment design: making assessment work better for students’ Professor Sally Brown (Leeds Beckett University) and Professor Kay Sambell (University of Sunderland and University of Cumbria).

The second keynote was delivered by two well-known names in the world of assessment and feedback. Professor Brown and Professor Sambell argued that all assessments should have some aspects of authenticity in them. They went through the benefits of assessment for learning which focuses on the process rather than the product, often mirrors real, complex challenges and equips students to work with uncertainty. Inviting students to produce a diverse range of outputs advances students’ sense of agency, develops their evaluative expertise and self-regulation and causes students to reflect meaningfully on their learning. They reviewed definitions of authentic assessment, preferring Lydia Arnold’s (2022) definition of ‘relevant’ assessment which focuses on tasks which have relevance to future employment, advancement of the discipline, our collective future, and individual aspirations.

They went through six steps to designing authentic assignments, providing some examples to demonstrate the many alternatives to traditional essays and unseen exams. Finishing with some examples taken from the curation of assessment examples they collected during the Covid pandemic. They were a great double act, touching on the use of generative AI or as they referred to it ‘Chatty G’ and its implications for assessment as well as discussing ways that peer and self-assessment can be built in to avoid excessive workload when designing multiple task assessments. They had some great ideas for assessment design and I would recommend looking through the guide they developed for Heriot Watt University for some inspiration on Choosing-and-using-fit-for-purpose-assessment-methods-1.pdf.

Student partnerships

The two talks on student partnerships indicated the positive impact of student collaboration.

The development of inclusivity student partnerships, Claire Ashdown, University of Leicester

The first talk was on a curriculum change project set up by the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion team at the University of Leicester. The aim was to develop student partnerships within departments to work on curriculum change projects to make students experiences more inclusive. Claire was refreshingly honest about the problems associated with setting up the programme. Documenting the various iterations that the team went through in attempts to get departments and students to work on projects together. The scheme encountered issues with; a lack of buy-in, inconsistent format and lack of structure or scope, unsuitable recommendations, unplanned increase in workload, frustration at staff not being available and difficulties in building up relationships with staff and students. The team used the theory of change to break down the project and work out a structure with evaluation built in and the current format seems to be working. Twelve students are recruited into a pool of paid consultants for 1 year and are given training on data collection, data analysis and running focus groups. Staff then propose the projects and students are allocated to them. Each project also has a staff project lead and a deputy to work as a second point of contact if needed. The requirements and expectations for the role are clearly stated from the start with evaluation points throughout. Students lead on the projects and meet once a month to share how things are going. The recommendations for each project are delivered in a final report with 85% of recommendations accepted in 22/23 as opposed to only 59% in 21/22. The student experiences are positive as they feel they are being listened to and the University is interested in their opinions, they feel more integrated into the department community, and they are more likely to get responses from their peers about the experiences on their course. The aim is to share project recommendations across departments so that successful changes will start to be disseminated more widely.

Biosciences peer mentoring programme: enhancing learning through student partnership at UEL, Emma Collins, Stefano Casalotti and Elizabeth Westhead, University of East London

The second presentation was on departmental student partnerships but this one was unpaid and was for peer mentoring. Set up for third year undergraduate students to support first year undergraduate students in large practical lab sessions. Three to five students are recruited for each module, and they must have a minimum average mark of 65% in the previous year and in the module, they will be supporting. They are given a lab skills evaluation, in which staff observe them doing a practical. Once recruited they commit to three hours over the eight-week term. They are given a refresher on lab techniques, health and safety training and a discussion with staff on the areas that students might struggle. They are given access to a Teams site with lesson plans and the opportunity to ask tutors questions. They are then timetabled to support large practical sessions with 120 students, where they demo techniques and answer queries.

Feedback from students has been positive as they find the mentors more approachable than staff and build up a relationship with them over the term. The mentors find having to review and go over previous years’ material helps to consolidate their learning and their current study. Having to think on their feet and answer questions in the labs develops their confidence and presentation skills and is great to put on their CV. They also feel more involved in the programme and are able to give feedback to staff from the students’ perspective.

Currently the scheme is being run on limited numbers of modules and is being supported by a small volunteering team. They plan to carry out more evaluation on the impact on student experience, learning engagement, motivation, performance, student experience, careers and employability.

The final panel discussion focused on Assessment for and as learning.

All the panel members agreed that assessment should be a learning process. Students come from a variety of backgrounds with very different previous experiences of assessment. In many cases they are being prepared for a career that will most likely not be in the UK. With this in mind we have to ensure students understand why they are doing assessment and understand it’s value and relevance. We need to get students intrinsically motivated in learning, to build up their self-confidence and encourage them to work in different ways and value peer feedback.

If you are want to find out more about giving effective feedback, the UCL Arena Centre are running an online workshop on 7 February from 11-12pm.

References

Sally Brown website: https://sally-brown.net/

contains: Assessment examples they collected during Covid pandemic https://sally-brown.net/kay-sambell-and-sally-brown-covid-19-assessment-collection/

Guide for Heriot Watt University: Choosing-and-using-fit-for-purpose-assessment-methods-1.pdf (1202 downloads)

Nash RA, Winstone NE. Responsibility-Sharing in the Giving and Receiving of Assessment Feedback. Front Psychol. 2017 Sep 6;8:1519.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01519. PMID: 28932202; PMCID: PMC5592371.

Robert Nash & Naomi Winstone When feedback is forgettable guest blog post on learning scientists blog, published 14 March 2018, accessed 23 January 2024 at https://www.learningscientists.org/

Naomi E. Winstone & Robert A. Nash (2023) Toward a cohesive psychological science of effective feedback, Educational Psychologist, 58:3, 111-129, DOI: 10.1080/00461520.2023.2224444