Author: Jennifer A. L. McGowan

jennifer.a.l.mcgowan@ucl.ac.uk

Abstract

Two frequently mentioned difficulties in teaching – both in person and online – are getting helpful feedback from students, and student engagement. In this case study I draw on an example for a psychology research module where we instigated opportunities across the year for students to provide ‘advice for future students’ on what they enjoyed, what may be difficult, and what to expect across the module.

Students not only engaged fully with this activity, but reviewed the experience positively for their own learning (in an independent focus group). By providing this advice to other students rather than staff, students felt more comfortable giving full and frank feedback, and felt that they were being an active part of’ the course learning experience. The feedback provided was rich and constructive, and so improved the lecturer’s ability to adapt the course in response.

Introduction

We are all repeatedly reminded that student feedback is key to providing effective teaching. However, it is often very difficult to receive useful levels of feedback from our students, which undermines efforts to improve our work. In this case study module in particular, we were struggling to receive feedback from students – with only one student providing feedback (out of 26) this academic year. Additionally, UCL’s education strategy encourages us to improve student engagement and leadership in our work – including providing links for students to collaborate between year groups.

In response to these needs, alongside our usual feedback form, we instigated opportunities across the year for students to provide ‘advice for future students’ on their experience of the module. We were unable to find previous literature on this specific idea – and it may not yet exist. Instead when designing this task we drew on several common ideas from psychology:

- That students are more likely to engage with a task if they feel that they have some say in the discourse (Davison and Price 2009), and in particular if they feel that their response will have some use to others.

- That students are more likely to engage with a task if it fits one or more of their three basic needs (Deci and Ryan, 2000) – autonomy (a need to have free will), relatedness (a need to feel connected to others), or competence (a need to feel effective or knowledgeable).

- That students will feel more comfortable talking honestly to their peers than to their teachers – especially where there may be implied criticism of their teachers (Veeck et al. 2016).

- That, especially in adolescents and young adults, peer advice is more likely to be followed and have a greater impact than advice given by a teacher (Epple & Romano, 2011).

…therefore by providing students with a task that provides these opportunities we were more likely to receive good quality feedback, and students were more likely to have a positive engagement experience.

Additionally, recent literature suggests that qualitative feedback provides richer data for course improvement than quantitative (Alderman, Towers & Bannah, 2012), and so we chose to provide a non-questionnaire option for feedback.

Methods

We developed this new feedback form based on the popular ‘keep, lose, change’ system utilised at UCL, and so based the ‘advice to future students’ on what part of the course were good, less good, or may be challenging. More specifically students were given the opportunity to provide advice on:

- Things to look forward to

- Things that will be more difficult

- Things you’ve learned

- Things you wish you’d known earlier

- General advice

The feedback forms were provided at the end of the course, as well as after each assessed assignment so that students had the opportunity to provide advice when it was fresh in their minds. Although moderated for appropriate language (no changes thankfully needed), the documents are intended to remain on the module year on year and provided directly to next year’s students to support them in their studies.

Results

The first result was that student engagement went up from one student (3.8%) completing the questionnaire, to 26 students (100%) completing the advice form. We additionally received ten full pages of feedback, in the form of advice to future students, for our module. Although it is impossible to provide all the feedback here, we were able to use this to identify what students commonly enjoyed about the module (leading and engaging in weekly discussions (N=17), trying out various applied research methodologies (N=9), the interactive elements of the lectures (N=8)), and what they had more difficulty with (leading a discussion (N=10), writing the self-reflective essay (N=8), getting up at 9am on Monday (N=5), the workload (N=4)).

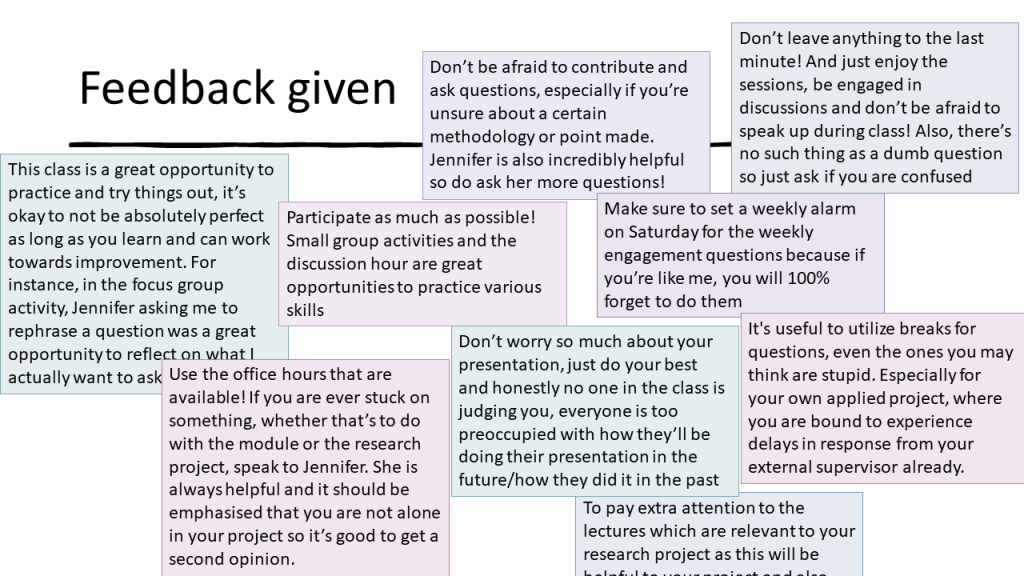

We additionally were able to learn that although students found these things difficult, they (with the exception of the “Monday” problem) nevertheless framed them as positive learning experiences and so that they found the module challenging, but also rewarding. Students also took this opportunity to provide general advice to future students (see image) which, although all things that we encourage from students on a daily basis, may have more impact when coming from peers – we will have to wait to see.

Summary

In summary, we found that by providing students the option to provide feedback to their peers, rather than teachers, and in a way that felt ‘useful’ or ‘collaborative’, we received feedback which was rich and constructive, and so improved the lecturer’s ability to support the course. We believe that this may be because students felt more comfortable giving full and frank feedback in this specific situation.

As well as helping us, we believe that this exercise was a positive experience for the current students, and will be of use to future students as well, thus supporting students across the year groups.

Video blog

References

Link to Deci & Ryan’s three basic needs, or link to a more accessible summary.

Epple, D.; R. E. Romano (2011): Peer Effects in Education: A Survey of the Theory and Evidence. Handbook of social economics 1, 1053-1163.

Freeman, R., & Dobbins, K. (2013). Are we serious about enhancing courses? Using the principles of assessment for learning to enhance course evaluation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(2), 142-151.

Davison, E., & Price, J. (2009). How do we rate? An evaluation of online student evaluations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 51-65. doi:10.1177/0273475315619652

Alderman, L., Towers, S., & Bannah, S. (2012). Student feedback systems in higher education: A focused literature review and environmental scan. Quality in Higher education, 18(3), 261-280.

Veeck A, O’Reilly K, MacMillan A, Yu H. The Use of Collaborative Midterm Student Evaluations to Provide Actionable Results. Journal of Marketing Education. 2016;38(3):157-169.

Image source: UCL Image Store – UCL Careers event