Author: Silvia Dal Bianco

Introduction

Data shows that there is a statistically significant discrepancy in the rate of good degree classes achieved by Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) students compared with white students in the UK. In 2017/18 there was a 3.3% good degree awarding gap between non BAME and BAME UK domiciled students across University College London (UCL). Chaudhury et al. (2019) documents a 6% awarding gap at the UCL Faculty of Social and Historical Sciences, that remains largely unexplained by observable characteristics such as parental background and prior attainment.

This post is a reflection on the interrelationship between assessment, inclusivity and the BAME awarding gap. It focuses on the experience of the Economics Department at UCL. It highlights the strategies that have been implemented for making assessment inclusive as well as the recent developments for fulfilling UCL strategy of closing the BAME awarding gap by 2024.

The interrelationship between assessment, inclusivity and the BAME awarding gap could be explained as follows. There is robust evidence in the literature that mixed -or multimodal or multicomponent- assessment strategies are a tool for catering for different learners and, thus, they are more inclusive than 100% exam assessment routines. Then, as the BAME awarding gap is defined as the difference between the number of white UK students awarded first-class or 2:1 degrees compared to Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic UK students, it is evident how good performance in assessment matters for closing the gap. Hence, the more inclusive the assessment, the smaller the BAME gap.

As it will be explained below, in the last decade, the Economics department at UCL has embarked in huge changes in assessment patterns, making multicomponent assessment the norm rather than the exception. Despite this, the awarding gap in economics has not been closed and it has fluctuated over time at degree classification level. My colleagues at CTaLE (Centre for Teaching and Learning Economics) and I have interpreted this fact as a sign that more needs to be done to understand the root causes of the BAME awarding gap. This is why we have designed and we are implementing a student-staff partnership project aimed at narrowing the gap at our department.

The rest of the post is organised as follows. The first paragraph reviews few selected literature contributions on assessment and cultural diversity. The second paragraph presents some data evidence on the BAME awarding gap at the UCL Economics Department. The third reviews the assessment Statu-quo at the Economics Department. The fourth describes a recent project aimed at narrowing the BAME awarding gap at the UCL Economics Department. Final remarks conclude.

1. What the literature says about cultural diversity, inclusive assessment and academic performance

Diversity can be defined in many ways. The existing literature has focused on the following variables as a measure of diversity: gender (Gossweiler and Slevin, 1995; Read et al., 2005; Read et al., 2001; Francis et al., 2001; Martin, 1997; Cabrera et al., 2002); learning styles and capacities (Marton and Saljo, 1976; De Vita, 2001; Anbarasi et al., 2015; Laird, 2011; Carinni et al., 2016; Dolar and Suny, 2018; Al-Bahrani et al., 2016); cultural and linguistic diversity (McGuire, 2007; Kaur et al., 2017; Sweeney et al., 2008; Cabrera et al., 2002; Lundberg, 2012; Hahn and Jang, 2012; Vita, 2001; Latif and Miles, 2011); and academic preparedness i.e. first-generation university student (Padgett et al., 2012; Ernst and Colthorpe, 2006; Geide-Stevenson, 2009). This blog post will focus mainly on cultural and linguistic diversity as this dimension seems to be the more closely related to ethnicity and thus to the BAME awarding gap.

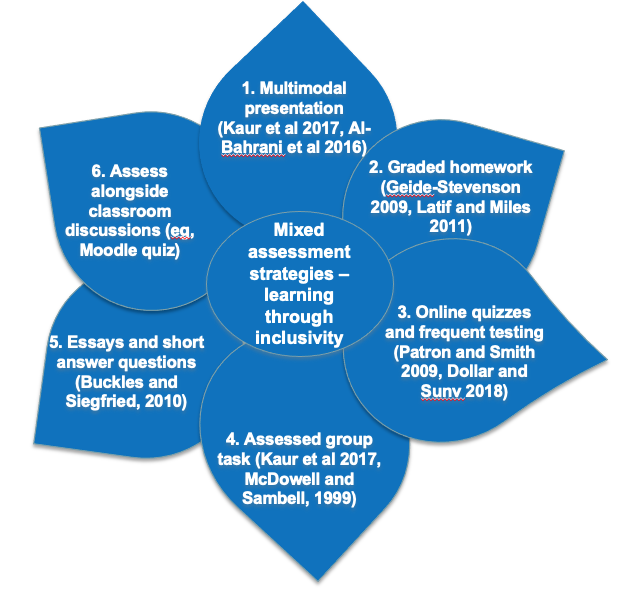

The majority of the literature emphasises the importance of multicomponent assessment, in contrast to 100% final exam, for diverse learners. Figure 2 illustrates the Mixed Assessment Flower, as in Dal Bianco, Jenkins and Chaudhury (2019). This is a representation of the variety of assessment that could be employed, with a specific reference to the field of economics. The idea behind being that mixed assessment strategies are a tool for catering for different learners and, thus, they are inclusive. Moreover, multimodal assessment can improve student outcomes and student experience because, for example, learners choose modules with assessment strategies that suit them best and do better as a result; learners receive feedback during the year, take feedback on board and do better as a result; and, finally, learners spread load of work and assessment, resulting in less stress at peak exam period.

For what concerns cultural differences and the effect of race on students’ performance, there seems to be robust evidence that mastery of English is associated with better performance (Stevenson, 2018; Li, Chen and Duanmu, 2010; Parker, 2006). Moreover, Stevenson (2018) found that English proficiency matters, but at a diminishing rate as students progress with their studies. Moreover, Jayanthi et al. (2014), Yousef (2011) and Stevenson (2018) all found that international students perform significantly better than local students. Jayanthi et al. (2014) explained this by the fact that overseas students cope with their high level of stress (Nasirudeen et al., 2014) by focusing their attention on academic achievements (Chu et al., 1971; Dozier, 2001). Moreover, Jayanthi et al. (2014) show that international students have higher incentives to do well, as often the continuation of their fundings depends on academic performance.

To summarise: mixed assessment strategies have to be preferred to 100% exams because they can cater for students’ diversity. However, assessment should be accompanied by a wider strategy aimed at a better understanding of BAME students and their needs.

2. The BAME awarding gap at UCL Economics

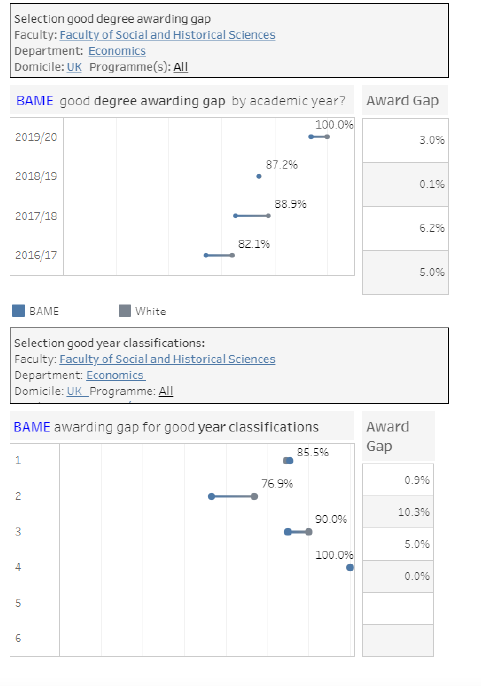

The BAME awarding gap in Economics has fluctuated over time at degree classification level. Figure 3 also shows that the gap is particularly large in the second year.

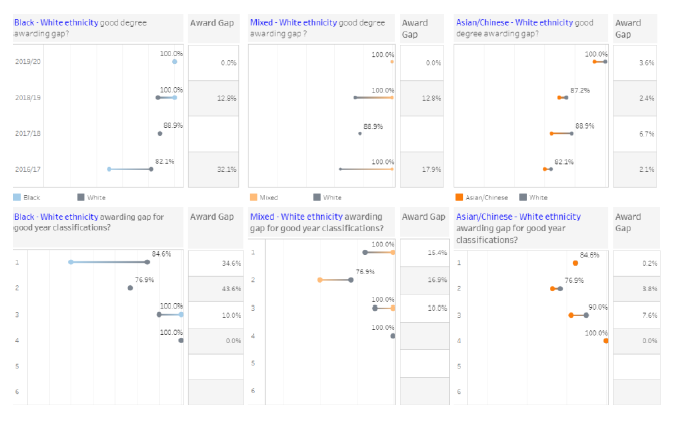

Figure 4 disaggregates the gap by ethnic groups. It could be easily seen that there are main challenges with Black and Mixed-Race students in the cohort.

In order to get a better understanding of the BAME awarding gap and the actions needed for closing it, my CTaLE colleagues and I have also collected qualitative feedback from UCL Economics BAME students in June 2021. Respondents indicated that they struggle to understand what is needed to do well and they lack confidence in seeking support. Hence, ‘hidden curriculum’ may explain the gap in part. For example, critical thinking is a popular goal of many economics courses, Siegfried and Colander (2021). However, BAME students’ cultural background might have been inspired by a mnemonic learning style, Seo (2020). These contrasting perceptions could widen the BAME gap. Hence, a deeper understanding of BAME students needs and experience is of paramount importance.

Another tentative explanation might be related to the fact that staff does not acknowledge BAME students’ diversity in terms of learning styles. This kind of narrative has been recently put forward in a BBC radio interview. Thus, the idea in this case would be gaining a better understanding of learning styles for a more effective assessment design. This line of investigation is left for future research.

3. The assessment mix at Economics

In the last decade, the Economics department at UCL has embarked in a process of profound renovation of the assessment portfolio. While in 2012/13 almost all modules were assessed with 100% summer term exam, in 2018/19 less than 50% were assessed through final exams. Such a proportion has been drastically reduced due to the COVID pandemic in 2020/21, where final closed-book exams have been turned into timed, often open-book, coursework.

4. How Economics is acting on the BAME awarding gap: the project brief

In November 2021, the UCL BAME Awarding Gap Fund awarded myself (Dr Silvia Dal Bianco) and my (then) colleague Prof Cloda Jenkins and Prof Marcos Vera Hernandez almost £25,000.00 for a three-year project aimed at contributing to the reduction of the BAME awarding gap in our BSc Economics programmes by 2024, in line with UCL commitment of closing the gap by that date. The project features two main interventions the:

- Creation of the Student Inclusivity Champions Panel, providing a vehicle for the BAME student voice to ensure academic and careers support;

- Introduction of the Second Year Challenge (SYC) group video project.

This challenge will be open to students entering their 2nd year of studies and it will be run just before the beginning of the “new academic year”, hence towards the end of September. Such interventions should trigger the mechanisms for narrowing the BAME gap. On the one hand, thanks to the Student Inclusivity Panel, BAME students having a stronger voice to be able to tell when challenges arise; and, on the other, the Second Year Challenge will reinforce BAME students’ sense of belonging to the Economics Department community. We also expect that the enhancements from the project interventions will benefit the Economics’ Department very large student body, with enrollment of about 1,100 students in 2020/21 across our BSc programmes. This is more than one third of the overall Faculty of Social and Historical Sciences and around 5% of UCL’s undergraduate student body.

The project features important collaborations between staff and students as well as intradepartmental collaborations. For what concerns the former aspect, the Student Inclusivity Champions Panel is composed by 8 undergraduate students from the Economics BSc programmes. The panelists have been appointed in December 2021. All of the panelists are of BAME origin and they are representative of the UCL Economics Dept cohort size-wise (i.e. 3 first year students; 4 second year students and 1 third year student). The panel gender ratio is skewed in favour of females (i.e. 3 males and 5 females).

The project can also count on the help of a Post-Graduate student from the UCL Institute for Global Health. In terms of departmental support, there are regular meetings to ensure ideas are taken forward as well as to find synergies and productive intradepartmental collaborations.

The panellists have been very active and they have designed a survey to better understand students’ engagement level with UCL resources; students’ ambitions; students’ sense of community; and, finally, potential sources of pressure within and outside UCL. They are also planning to establish a series of inclusive careers’ talks, to offer BAME students actual role models; as well as the organisation of informal drop-in sessions for students to seek information and the possibility to have an open chat.

No data from panellists’ investigations is available yet. Similarly, SYC’s development is still in its initial stage. Reports on findings is thus left for near-future research.

5. Conclusions

This blog post has shown our interventions for closing the BAME awarding gap at the Economics Dept. Our strategy acknowledges the fundamental importance of a mixed assessment strategies as well as the relevance for BAME students to have a voice with their peers and reinforcing their sense of community. These facts are key to ensuring BAME feel confident and do their best academically.

This research opens interesting further lines of investigation. For example, on the impact of a deeper understanding of different learning styles on assessment design and the BAME gap. This is left for the future as it requires huge data collection efforts, in terms of survey design and responses’ collection and analysis.